Mainstream management after decades of lean

FEATURE – Lean has now been around for quite some time, and its impact on business world is hard to dispute. But what does it tell us about traditional management practices?

Words: Michael Ballé, Daniel T Jones and Jacques Chaize

Lean thinking leads to a very different way of forming opinions, fostering involvement, making decisions and, more in general, acting. It is as far from Taylorism and financial management as it is from the holacracy “no management needed,” self-organization approach.

Nonetheless, the clear barrier to entry is that adopting lean requires learning the lean system on the shop floor, firsthand. This is a commitment many managers hesitate to make, preferring to latch on to this or that tool and believe that it will improve their current management practice enough to make a real difference.

Our experience, however, is that practicing the full learning system, as originally ironed out by Toyota and then transferred to many different contexts, is necessary to really figure out how to manage differently, align people development with customer satisfaction and grow organizations sustainably and profitability.

In our latest book, The Lean Strategy, we have shared the experience of several CEOs having made this journey and radically changed the way they ran their businesses by practicing the lean learning system (the “Thinking People System” in Toyota terms). These leaders visibly changed the story of their firms by first changing their own personal story.

So, having reached the other side of this wide river, what can we say of mainstream management practices after three decades of lean thinking? This is a very practical question lean CEOs are faced with every time they recruit a manager from a traditionally thinking company. How they can get the newly-hired to understand how critical visual management is, what the company is trying to achieve with lean, and so on, is of the utmost importance.

INTENT

The first difference that stands out is the clarity of intent. Lean management considers the full human being – minds and hearts as well as hands – and accepts (counts on, in fact) that every employee must understand the purpose of what they’re asked to do or have to do in their daily job in order to perform it well, and derive satisfaction from it.

In traditional management, people are asked to do a job based on their established role as defined by the organization, or to carry out a decision taken by their superiors as they’re told, preferably without asking questions. The focus in on command (do this) and control (making sure it gets done) and not on explaining “why?” or “how?” This time-resistant trait is built into the mechanistic design of organizations inspired by 19th-century armies, and remains embedded in management thinking even when modern military operations have actually caught on to the need to explain “intent”, discuss and question plans ahead of carrying them out.

Visualizing intent, by contrast, is part of lean’s DNA and appears at all level, with:

- "Kanban and Andon" to visualize the next step in the process and who to ask for help if something feels fishy or too hard, which gives meaning and direction to the job on a hour-by-hour basis.

- Management “obeya” rooms, where overarching goals and targets are spelled out and displayed for all to see, together with managers’ individual plans to achieve them;

- Individual A3 “hoshin” documents detailing how each person understands their challenges, results from previous efforts, current goals and targets and detailed planned steps to achieve them;

- And daily team stand-up meetings detailing the day’s plan and discussing issues, as well as flagging up events or special circumstances.

SKILLS

Lean’s unique focus is on the “process point” – where the tool touches the part, where the salesperson speaks to the client, where the customer uses the product or service. As a result, lean is primarily concerned with the skill of the employee that handles the tool, carries out the transaction or designs the product. Contrarily to mainstream management that considers all situations roughly the same (Ford’s main innovation was to standardize parts so they could be fitted without adjustment, which meant that an operator could pick a part in a jumbled bin and, if it didn’t work out, throw it and pick another one), lean thinking accepts that every new operation takes place in a slightly different context – every flash of welding is minutely different from the one before as the tool is a bit more worn out, the parts are slightly different, conditions of pressure, temperature and dust change, and so on.

Skills, therefore, are as much about doing the right thing as they are about doing the right thing in an evolving context, which involves, first, understanding different standard contexts and, second, having the right gesture for each – “kata” in the Japanese sense of the term. Flexibility is about being able to move seamlessly from one situation, and one reaction, to another.

Beyond clarifying all the time the intent of the task at hand, lean therefore constantly focuses on developing skills, and does so by endlessly focusing on remastering the basics. This means practicing standard activities and delving deeper into the theory of core actions. But secondly, it means investigating how these basics work out in borderline conditions and asking searching, enquiring questions: how is this different? Why is this happening? Is this a fluke attributable to a special circumstance, or is this a common cause and conditions at large are changing?

Skills development is really about developing the confidence each person has in how to: recognize the task at hand, by knowing what needs to be done in situ; handle the task at hand by mastering the basics through endless practice; and copy smartly with specific contexts by also studying odd situations and outcomes and delving deeper in the theory and practice of the task to understand it further. These three elements are essential to lifelong learning of one’s job.

AFFECT

Because lean thinking is all about involving people deeper with the intent of what they do and their skill in doing it, how they feel about things is of foremost importance. To affect is to touch someone’s feelings, or to move someone emotionally. “Affect” is someone’s emotion or desire that influences behavior, the emotional side of motivation as opposed to the rational, calculating side of fearing consequences or seeking a reward.

In contrast, deeply influenced by mechanistic bureaucratic thinking, traditional management dismisses and ignores affect – considering people just have to do what they’re told and how they feel about it is their problem (“it’s business, leave your personal feelings at the door”). By contrast, lean thinking considers that how people feel about what they’re asked to do is key to success.

People’s feelings are certainly their own, but management attitudes can create the conditions for either negative or positive feelings. By clarifying the challenges that need to be overcome together, managers can drum up enthusiasm. By recognizing the difficulties people face on the job and helping them with them, managers can foster trust. By displaying competence in hairy, ambiguous situations, managers can cultivate another form of trust – the confidence that officers know what they’re about and that the company has a future. Finally, by being fair in their assessment of each person’s effort and understanding of individual circumstances, managers can create an atmosphere or fairness and, yes, once again, trust.

The management of affect starts with a skill that is commonly praised but rarely developed as it is in lean thinking: listening. Listening in the sense of observing deeply with the person and imagining a world in which what they describe is exactly true – even as one disagrees. Understanding does not mean agreeing, and listening should, well, be painful. As human beings, most of our thinking is what is called in psychology “motivated” – stacking the facts in the way of justifying an a priori conclusion. True listening is about using one’s mind as a scout, not a warrior. It means figuring out what the other person has in mind before trying to persuade them or coerce them to adopt our point of view. In lean, listening has more to do with going to the real place, see the real part and the real conditions and hearing what people think about it than with conversation style. This is about genuinely trying to stand in the other person’s shoes.

TEAMWORK

There are few positive feelings at work more powerful than being part of a team, where one engages in a common purpose and is accepted without reservation, moods and warts and all. Similarly, there are few things as personally enriching as working closely across the aisle with someone with a different specialty or from a different department. Teamwork is about everyone understanding goals and striving to reach them together, which means helping each other to get there. It is also about supporting colleagues who seek other roles or responsibilities as much as lending a hand in group improvement activities. Teamwork is equally about accepting help as it is about giving it. The basis of teamwork are individual skills, and the helping hand attitude to put them to use effectively. The company cannot succeed as a whole at delivering quality products on time if each person doesn’t find their success within the business and if people don’t help each other across functional boundaries.

A recurring feeling in traditional organizations is that if everyone did his or her job well, all would be fine. If each of the cogs functions properly, so to speak, the machine performs efficiently. As we all know, however, the machine does perform in the end, but far from smoothly and even further from effectively. Lack of teamwork from ground teams requires going up the channels through long, cumbersome processes, which are almost always hindered by middle-managers protecting their bosses from bad news, while the bosses themselves indulge in turf wars and brinkmanship. The frequent outcome of not encouraging teams to work with each other in the value process itself is that silos pursue functional objectives defined by each functional culture (HR does HR things, production does its production things, engineering… and so on), and customers are treated as numbers on a spreadsheet.

Teamwork starts with a commitment to individual, personal development and a realization that people influence each other tremendously. Executive energy in treating each person as an individual is key to the vitality of the teams and the vigor of the company. Leaders have the ability to energize others by giving realistic challenges and fostering a sense of accomplishment. Showing respect to each person is the key to engaging one and all in taking initiative with confidence (both self-confidence and trust in others), thus building involvement within local teams and with the company as a whole. As opposed to traditional mechanistic thinking of command-and-control, one-best-way and pay-for-performance, lean adopts the language of individual energy and shared achievement: talent, passion and the constant search for a better way, together.

RELATIONSHIP OF PEOPLE WITH THEIR WORK

Right from the start, management has had an enduring dream of mechanizing, automating and, now, digitalizing. The driving idea is to replace labor with machines, people with robots and management with IT systems. Not surprisingly, Big Company management seems to resent people for not being automatons, and tends to treat them as is they were. This is plain silly as, in the end, products and services are made for people by people. Still this cold, ruthless approach to employees has generated, understandably, the opposite view that industry should return to craftsmanship and workers be left to autonomously define and carry out their work without management interference. Both ideas are extremes of the same bureaucratic paradigm where roles, responsibilities and systems designed by specialists trump the human being and force a by-the-numbers “rationality” on one and all.

Lean ideas emerged from asking the question of automation completely differently. Toyota’s original founder, Japanese inventor Sakichi Toyoda, first invented a wooden mechanical loom that would support his mother’s weaving and lighten her work burden. When he mechanized the loom, he first made the shuttle change automatic, and then invented the famous “andon” system that stopped the machine when a cotton thread broke to avoid producing faulty material, thus freeing operators from having to babysit machines. In this vision of automation, machines do not replace people: people remain the craftsman, but the machine does the heavy lifting. Similarly, when Sakichi’s son Kiichiro started the automotive motor company, he came up with the “just-in-time” concept to find new ways to make people, machines and plants better coordinate and work together to create value without generating so much waste. Finally, when the legendary Eiji Toyoda took over – the architect of the Toyota we now know – he understood the importance of creative suggestions and saw how crucial good thinking was to good products. Machines can’t think, robots can’t improve and IT systems can’t change.

Lean’s unique perspective is that rather than focus on work (as Taylorism has done) or on people (as the opposing Human Relations has done), it looks at the relationship between people and work: how employees understand the purpose, impact and involved details of their work, and how this work relates to customer satisfaction.

This creates a radically different approach to management where visual organization is essential to creating the “operative fields” in which the employees themselves, supported by management, can look deeply into how ways of working impact customers – both the next step in the process and the final user. Through the use of visual management techniques and a different attitude to work and workers, lean management clarifies intent, supports skill development, cares about affect and encourages teamwork.

Buy your copy here.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – 2019 was another momentous year for the Lean Community. John Shook reflects on what we lost and what we gained in the last year of the decade.

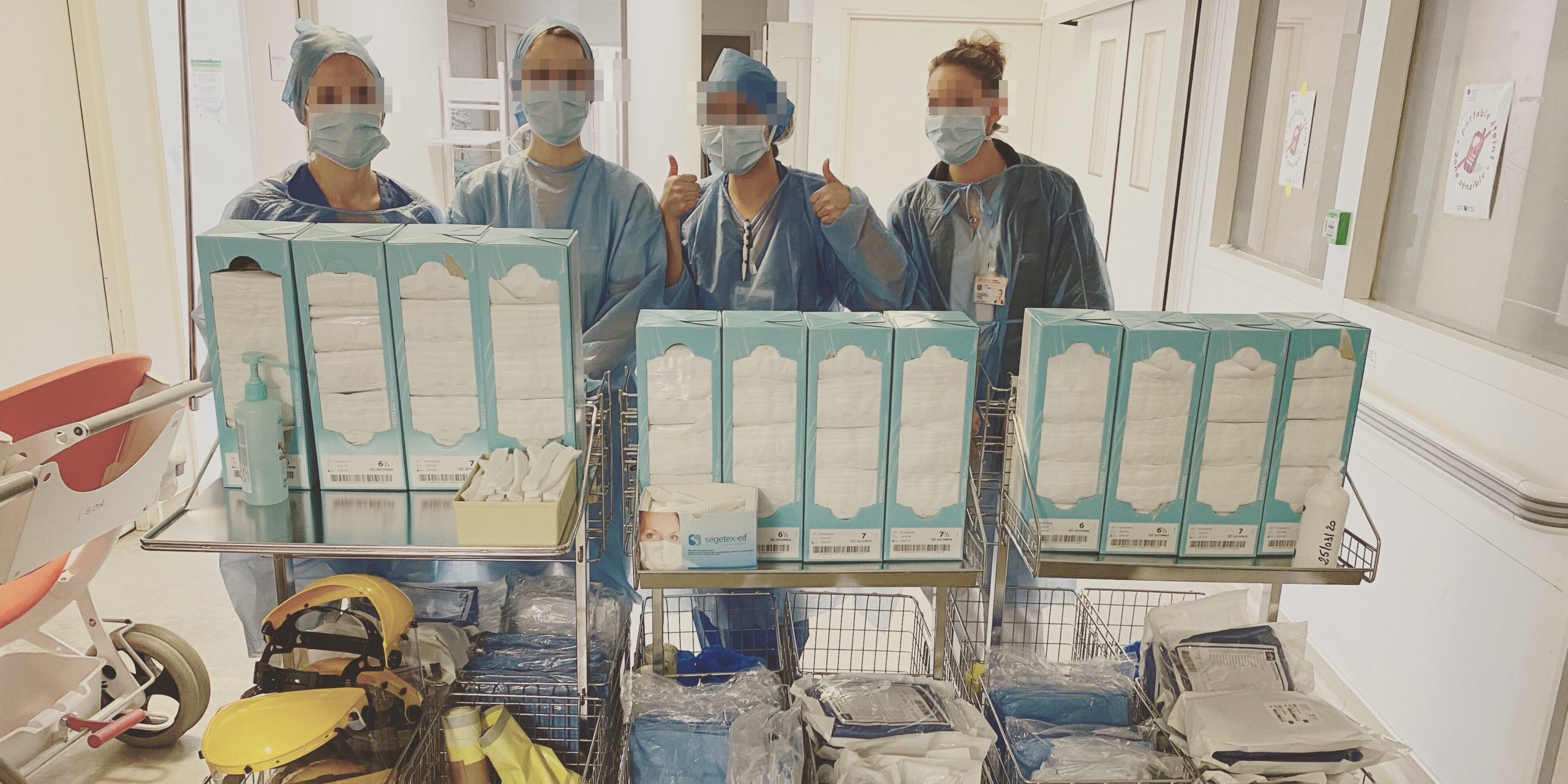

NOTES FROM THE (VIRTUAL) GEMBA – This small manufacturer is relying on Lean Thinking to keep the business running during the Covid-19 crisis, overcome the disruption in its supply chain, and even innovate.

WEB SERIES – In the fourth and final episode of Season 1 of our docuseries, we visit home improvement and gardening retailer Leroy Merlin and learn about their efforts to lean out their supply chain.

RESEARCH - This interesting study, based on 44 Volvo plants and 200 Volvo interviewees, looks at how the implementation of lean thinking influences a plant’s performance over time.