Understanding buffer limits in levelled production

FEATURE – Setting the right buffer limits and re-order point, triggering production of an item, is critical for an organization to manage inventory. In his latest article, Ian Glenday explains why, once again, picking flow over batch logic is a no-brainer.

Words: Ian Glenday, lean coach and author

The previous article in this series showed how demand variability for the 6% of products accounting for 50% of the volume produced, which we call the greens, is typically – at a percent level – far less than people realize. This means it is possible to have a relatively small buffer tank of stock to absorb the sales variation, hence protecting the fixed production plan and creating stability – which is the foundation of the Toyota Production System. It is this stability coming from a fixed schedule over 6 to 8 cycles that is the basis for achieving sustainable continuous improvement and standards.

The question now is how to set the limits and manage the buffer tank.

With batch logic, the planning system is trying to answer two questions for each product: when to make it and how much to make based on the re-order point, safety stock level and minimum order quantity. The most significant figure here is the re-order point as no production will be planned by the system until this is reached. It is the "trigger" that determines something needs to happen to initiate production of a product. Making sure it is correctly calculated is therefore crucial. Get it wrong and you will either make too soon, increasing inventory (which is of course a bad thing), or make too late, potentially leading to a customer service issue (which is a very bad thing).

With flow logic the calculation of how much of the greens to make and when to make it has already been done by people working together: essentially the planning system does not need to "plan production". What is required for this ideal situation to occur is a reporting process to highlight when stock goes outside the buffer tank limits – as a warning to look at it. Being outside the limits is not necessarily bad, and certainly should not be an automatic "trigger" to change the plan. The limits are merely the point that indicates it should be highlighted to the planner and they should investigate why this has happened. For this reason setting the buffer tank limits is not critical – they do not need to be "pin point" accurate as they do not "trigger" action and changes to the plan. Products will continue to be produced each week at the same time and in the same quantities: there is built-in stability in flow logic.

To determine the buffer limits one needs to look at actual sales variability. How much do the weekly sales, in percent terms, vary from the average weekly sales? If the sales are seasonal, or have periods of promotion, one needs to break the year up into representative sections or "blocks" and then use the sales variability in each of these "blocks" to set the limits. As was shown in the previous article, green items do not typically vary that much at a percent level. No more than plus/minus 20% compared to average weekly sales is common. To make the maths easy, if one takes a week as 5 days, 20% equals 1 day meaning the buffer limits are plus/minus 1 day around the average weekly sales figure. If the variability was say plus/minus 50% - which for a green item would be unusually high – then it would be plus/minus 2.5 days around the weekly average.

When calculating the buffer tank limits using actual percent sales variability one often finds the limits needed are less than the "sawtooth" produced by how frequently the greens are made in the fixed cycle. For example, if they are made weekly then the "sawtooth" of maximum (when production is received into stock) and minimum (just before production is received into stock) would be 7 days, wider than the limits needed from actual sales variability. So in this case – which is normally what happens - the limits have to be set at this plus/minus 3.5 days to prevent false reporting of stock outside the limits every week just because that is the frequency production occurs at.

After determining the width of the buffer tank limits, the next decision is what to set the lower limit at. Below the lower limit and zero stock is what is known as safety stock. With batch logic safety stock is calculated based on various considerations, such as production lead-time and reliability, sales forecasting accuracy (or rather inaccuracy!) and service level targets. One reason the safety stock is there because there is an amount of time between production triggered by the re-order point and when it is actually received. The actual time it takes varies. Safety stock in a batch logic situation is also there because of differences in production outputs versus plan, and actual sales versus forecast. Safety stock helps cope with these differences. With flow logic the production is fixed so there are no production lead-time issues. The buffer tank limits have been set using the known sales variability, which means the safety stock is only required to deal with truly totally unpredictable events and issues. How does one mathematically calculate a number for totally unpredicted events? I am not going to lie: it is very difficult.

The safety stock with flow logic tends to be more a judgement than a statistically calculated figure. People find this difficult to accept at first, having been used to calculating safety stock based on certain conventional batch planning logic algorithms. When determining for the first time what the safety stock should be most people decide to set it at whatever the current level is. It is a low-risk option and makes a lot of sense. It can be re-set – usually at a much lower level – when one has gained some experience of running fixed repeating cycles, once they have seen the level of stability it creates.

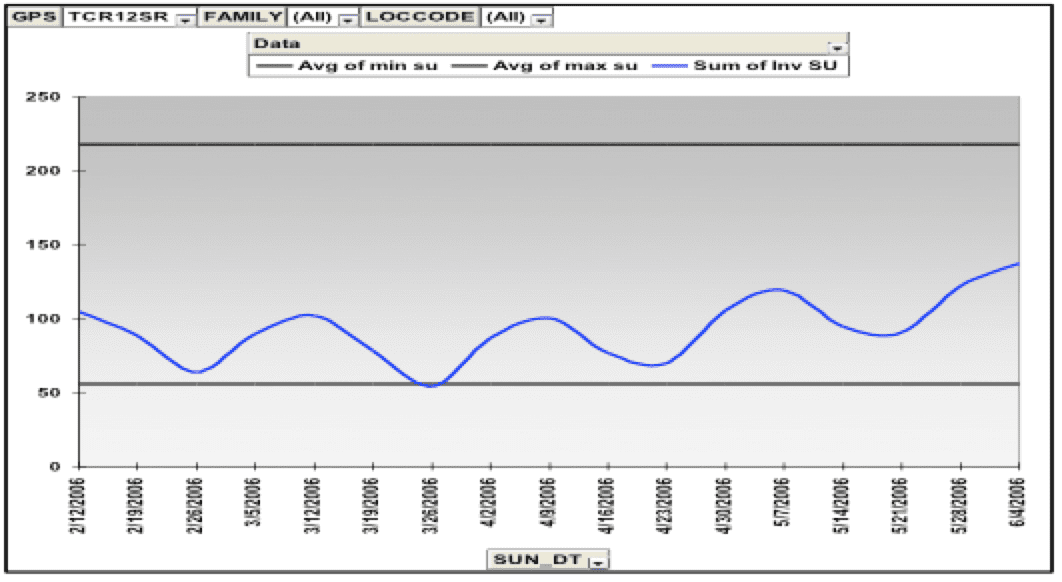

Having agreed the buffer tank limits it is important that a reporting process is put in place. First to investigate the reasons behind the presence of an item outside the limits, and secondly to help determine the buffer tank limits and safety stock for the next cycle. This reporting is the equivalent of a run chart in statistical process control and shows the actually inventory in relation to the limits as shown in the chart below.

It is quite easy to interpret the graph. In this example the upper limit was set too high, but it can be brought down. Although the lower level has been exceeded once by a very small margin, there is still quite a lot of safety stock – 50 units when the average weekly sales are around 75 units. The safety stock could be reduced bringing down the lower limit and creating an inventory saving. A saving that many companies in today's economic environment would welcome as a cash benefit.

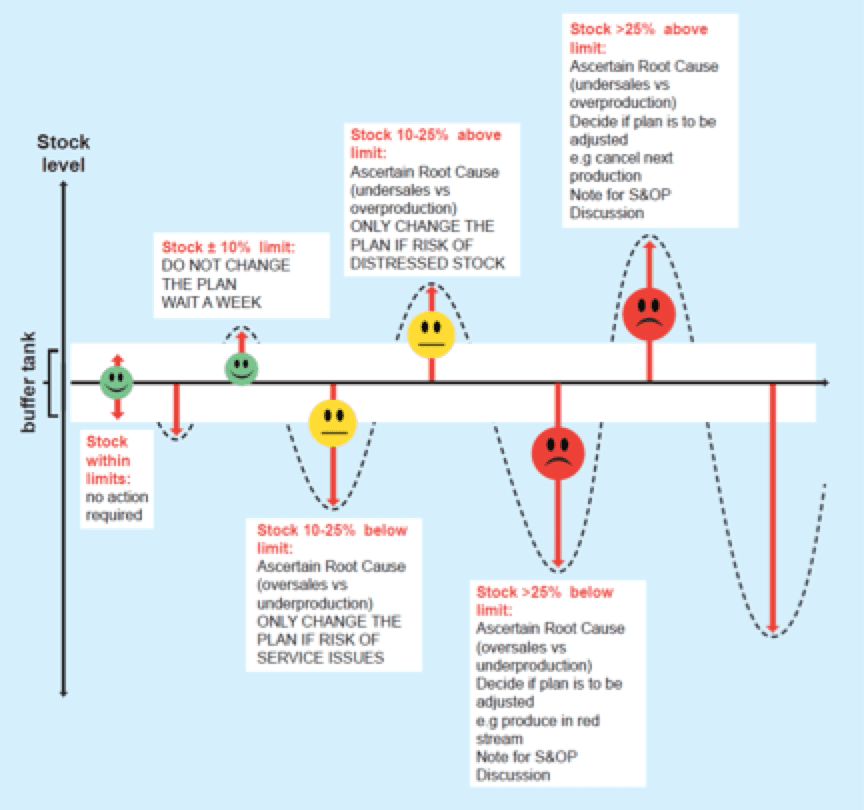

To help manage the buffer tank it is helpful to have a visual representation to show what should be done if any items exceed the limits. It shows inventory getting increasingly wide, with the appropriate action depending on how far outside the limits it is. Remember buffer tank limits are the same as those in statistical process control so going outside the limits should not trigger actions to change the plan, but merely to investigate the situation. The chart shows an example.

Three points are worth highlighting:

- the agreed action – when only a small amount outside of the limits, +/- 10% of the limit in this case – is "do not change the plan, wait a week". In other words even when the limit is exceeded it does not automatically trigger a change to the green stream fixed plan. Experience shows that generally if one waits another week there will be an opposite change in demand that will bring the inventory level back within the limits.

- the actions are an escalation – rather than a single response – giving appropriate action to the level of severity the inventory is outside the limits.

- it is worth remembering that as the limits have been set using actual sales variability statistically one would not expect the limits to be exceeded.

The articles in this series have so far focused on moving from batch to flow logic and how to implemented levelled production using the Glenday Sieve to identify the greens. How then to put these into a fixed repetitive schedule over 6 to 8 cycles protected by a buffer tank in order to create stability and the phenomenon of economies of repetition. The "greens" are typically only 6% of the items or activities that make up 50% of the volume or sales. At the other end of the Glenday Sieve are the "reds". These typically are only 1% of the volume or sales yet are a staggering 30% of items or work. The "reds" will never be part of a levelled production schedule as the demand for these items is highly variable and unpredictable. How does one deal with these items? This shall be the topic of my next article for Planet lean.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – The warehousing department of a Dutch hospital has been implementing lean for a few years. Its Head of Logistics believes in an approach to change based on respect for people and on making small but steady steps.

INTERVIEW – Dave Brunt tells us about the upcoming UK Lean Summit, one of the year’s must-attend events for lean practitioners.

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN – How it is that some ideas and innovations spread like wildfire while others are slower to take roots? It is clear that lean thinking belongs to the latter category, but how can we speed up its diffusion?

FEATURE ARTICLE – By adopting lean thinking and establishing a dedicated care pathway, a Brazilian hospital has been able to drastically reduce the time breast cancer patients have to wait to undergo surgery or start treatment.