Building our lean legacy

CASE STUDY – We hear from a construction company in Chile that embarked on a lean journey in 2018 to transform its culture and improve the work on its many sites.

Words: Daniela Bertin Figueroa and María Paz Mosqueira Arce

Lean Thinking came to Socovesa in 2018, but our first attempts to figure out a better way of working began three years before. Back in 2015, each of our construction sites was managed differently. They all had their own way of executing the plan. That’s when we first realized the need to centralize the control of our projects by standardizing our planning activities. We tried to find commonalities among the different projects and used a digital tool to try and achieve a clear overview of the progress in each of them.

However, we still had to wait for the data to be provided by each site, which happened when the team had the time to gather and upload it. That’s when we started to develop an Excel chart for online physical advance control of each project, which eventually led to the development of our in-house software, a repository of information we call Socoplanner.

At the end of 2017, after looking for ways to work in a more consistent way and communicate more effectively for nearly three years, we invited a Brazilian consulting firm to run an evaluation of our process. They came back with the suggestion of introduction Lean Thinking – a journey that continues today.

Our main problem was cultural. Before starting, our people rarely took the time to understand the details of the work they had to do and how it fit into the overall context of a project. Instead of asking questions about the unique characteristics of a project, they tended to assume – sometimes, they still do – that they could just handle it in the same way they always had. So, we typically began to build only to realize at a later stage that the characteristics of the building were very different than we thought. That means we had to improvise a lot to fight fires and solve problems that we wouldn’t have had in the first place If we had sat down at the beginning to really understand the work to be done.

HOW WE BEGAN

We started with two pilot projects: a block of 300 social housing units and a 20-storey building. In the latter, unfortunately, our impact was limited because we began when the project was already reaching completion. But in the first one, the learnings were truly great.

As part of that first pilot, we tried to use Last Planner System (LPS), a staple of project management in construction that we really see as another lean tool. LPS limits variability and helps us to carry out the work in a more efficient way. By introducing it, we began to make decisions based on data and demand transparency of the team. We set an expectation that there should be a common thread running from the master plan, through intermediate planning, all the way down to the weekly plan. These had to be consequential, and for that to happen people had to follow the standard and commit to doing their part of the work by the set deadline.

The team, therefore, had an Excel sheet hanging to the meeting room wall, which they updated as the project progressed. Next to it, there was a board with the names of each foreman, who wrote down what they were responsible for over the following week.

It was clear from the beginning that the hardest thing to change would be our people’s mindset – especially those with many years of experience in construction – who simply didn’t believe there could be another, better way of managing a project. Additionally, many didn’t like the fact that lean really means transparency: bringing problems to the surface makes you uncomfortable and we humans always prefer to pretend everything is going well.

Despite these cultural barriers, however, we learned a lot in that first pilot. That first direct experience with lean showed us, for example, how important it is to truly understand the nature of a project before it begins and to look ahead at parts of it that might feel far in the future but that we can impact very negatively today if we don’t plan carefully. That was refreshing, because historically we found out about problems way too late (sometimes to the extent that we couldn’t build a swimming pool, as per the original project, because there was not enough space).

One solution that came out of the pilot was to invite a planner – a lean facilitator – to each site to create a direct connection with central planning. Their role is not only to act as a bridge with the corporate office, however; they also support site managers in the every-day running of a project, enabling team problem solving and bringing the problem back to data whenever people are struggling to get to the bottom of it. As a result, teamwork has improved on our sites.

Of course, this system of standardization and chain of help is enabled by visual management and daily meetings. When we first introduced visual management boards in each site, the planner printed the sheets, but nobody read them. Then things changed, as people realized the new system would help them (each board has a section where best practices are recorded) and slowly began to use it.

Additionally, all good practices are recorded centrally and provided to any team that might need them on the ground: enabling reusable knowledge is part of our mission as a Lean Office.

SOLVING PROBLEMS IN A STRUCTURED WAY

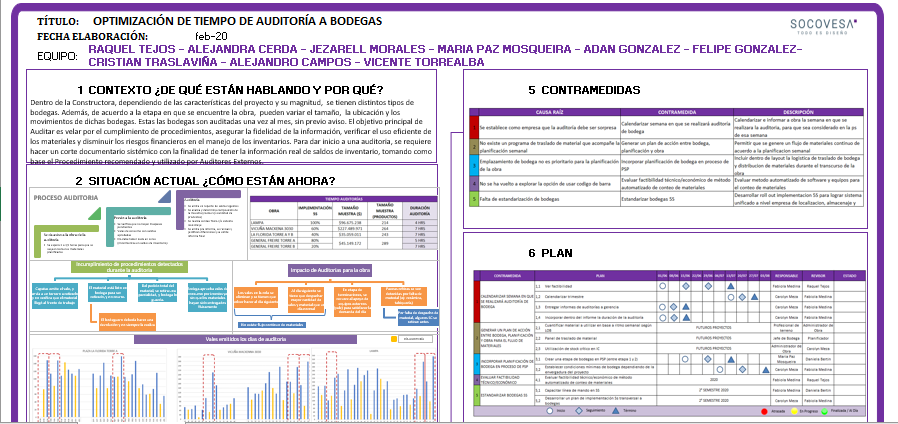

Even though we already had some experience with A3 Thinking, we wanted to become more fluent in its use. This led to our collaboration with Lean Institute Chile, which gave us the opportunity to get very deep into our understanding of each of the sections of the A3. With their help, we unlocked many of the secrets of this powerful problem-solving tool and learned to tap into its potential.

Our coaches from the institute taught us that an A3 is alive, so to speak, and that we are supposed to revise it all the time until we truly get to the solution we need.

Critically, the approach they invited us to follow entailed developing the entire A3 at the gemba. This was key, because it allowed us to try things out right there and then and improve our A3s in real time. The solutions we began to come up with, therefore, were fully connected to what happened every day on the construction site. When you join a supervisor to follow the flow of furniture in their journey from the producer to the site, after all, you learn things about the work that you simply cannot see from your office or from superficial conversations.

As part of our A3 training, we were divided into three teams and learned to work on our A3s until the second before the review meeting, to perfect them. At each review session, several learnings surfaced as teams presented their efforts and discoveries to other teams. We even started to value the perspective and criticism provided by others, something that gave pause to some people at first, as ways to further improve our problem-solving skills. To us, A3 Thinking was really a way to enable knowledge sharing across Socovesa.

COVID, A MAJOR SETBACK

Twelve people participated in the first training on A3 Thinking provided by Lean Institute Chile. Our next step was to have another 75 go through it, to further spread this knowledge across the organization. We were also going to start new projects and further explore the use of tools like Value Stream Mapping. But then the pandemic came.

Covid hit right after several weeks of social unrest here in Chile, meaning that the situation was already quite difficult to begin with. After months of lockdown, we got back to a world forever changed: we began to struggle with workforce availability and with huge delays in projects we had started long before the pandemic came.

All of a sudden, everything that was not urgent (and everything felt very urgent in those first post-lockdown months) took a back seat – including our lean efforts. People were resisting our attempts to reintroduce lean practices, saying there were more pressing issues to deal with. They seemed to have forgotten it all, and it took us a year just to get back to where we were before Covid.

We are putting the pieces together now, while trying to complete the work that is still pending before we can start some new lean projects (hopefully next year). The pandemic caused a huge setback in our journey, a somber reminder of how fragile lean is and how difficult it is to truly transform a culture and maintain hard-earned results.

If we can’t progress, we want to at least make sure we don’t retrocede too much. So, for each new project we start, we are running cycles of twelve 15-minute talks, one per week, focusing on one topic. It’s our way to conduct maintenance on the lean knowledge we had acquired. Of course, as a Lean Office, we also continue to provide support to our people whenever they ask for it.

With interest rates and prices increasing, achieving post-pandemic stability seems harder than ever, but we are confident that the lean practices we introduced will help us to get there. Thinking lean means you learn to make the work more predictable and to anticipate problems, so that you can attack them before they occur – or at least while they are small enough that you can solve them easily and cheaply. At a time of great uncertainty, this is critical. Lean can also help us to optimize the processes so that we can spend less money per building, which is very important for us at a time when prices of raw materials and products/services are soaring.

What we have tried to do with lean at Socovesa is to create a space for planning and thinking together, as a construction company rather than a bunch of individual projects. We like to think this will help us to weather the storm.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – Taiwan-based Machan International Co. manufactures sheet metal products, tool storage and medical trolleys, and smart energy storage cabinets. Last year, they turned to lean to improve their product development process.

INTERVIEW - Grey Dube reflects on the approach, challenges and successes of becoming a lean CEO, and on how this helped turn Leratong Hospital into a lean organization.

GETTING TO KNOW US – For our second interview with LGN directors, we travel to Hungary to meet the President of our affiliate institute there. He tells us his country’s need for good workers and how lean can make the difference.

FEATURE – In this compelling theoretical piece, the author reminds us how in a lean organization relations are structured around learning opportunities rather than execution. This is what ultimately enables a company to grow.