Lean as a two-step engine

FEATURE – One of the things making lean thinking so hard to explain in general terms is its dual nature as both an organizational and managerial approach. The authors explain how to handle this tension.

Words: Michael Ballé and Nicolas Chartier

Up until two years ago, growth at AramisAuto had stalled and marketing costs were going up faster than revenue. The founders knew they were in trouble, but were at their wits’ ends of how to approach the topic.

The CEO had tried various mainstream lean approaches, working with consultants to fix issues in specific processes. He’d found it promising because of the rapid gains, on paper, but found that these gains never materialized at company level. In fact, he realized that such performance-driven projects were simply reinforcing the “pillowcase syndrome”: squeeze here, and the waste moves elsewhere in the system.

Finally, he went back to basics: he re-read the Lean Thinking, found a sensei and started favoring inquisitiveness and participation over instant results. He began to use gemba walks as his main management tool: instead of reading reports and discuss them in the boardroom, he started going to the workplace to discuss issues directly with front-line staff and try to understand the situation rather than look for quick fixes. He also made teamwork his priority at department-head level: he set up an Obeya room, so that they could regularly explain to each other the projects they were leading in their functions and discuss how this would impact the company as a whole and how to better handle the synergies between various internal systems.

As a result of these changes, the customer satisfaction index (Net Promoter Score) increased by 25% and the employee satisfaction index (e-NPS) by an astounding 70%. “It’s like it’s a different company,” says HR director Brigitte Schiffano, “What we hear from the field is that people feel a lot safer in their day-to-day jobs. Managers are learning to take mistakes as learning experiences, which takes away much of the fear of being reprimanded if something goes unexpectedly wrong. Collectively, teamwork has considerably improved, as joint problem solving encourages helping each other across functions, as opposed to the turf wars and blame game we used to have like in any company I know. It’s a different place!”

In just two years, thanks to lean thinking, AramisAuto recaptured double-digit growth and doubled its profitability. Despite the remarkable improvement in internal satisfaction, when employees were asked directly what they thought of the company’s turn towards lean, their answers were lukewarm at best. An internal survey showed that senior managers were quite clear on what “lean” meant and on board, but the further down the ranks you got the more people complained about not understanding what it was about or not seeing the benefits, for either themselves or the company.

And there lies the rub: how to explain lean simply? Is a lean company a different form of organization with value streams, pull systems and line management focused on problem solving and kaizen? Or is lean best explained as a different form of management based on gemba visits, challenges, and self-study exercises rather than implementation and control?

The CEO used to see himself as a strong leader: take charge, make the right decisions, drive people to execute, praise or reprimand according to progress. And indeed, he and his co-founder have succeeded spectacularly in digitally disrupting the car sales business. But he’d also found that, 20 years down the line, leading an established company and keeping it growing was very different from running a start-up. He felt like he’d gone off the road and was now trying to drive in a muddy field. The complexity of every issue, the resistance to change of every team, the difficulty of procuring more cars to sell in saturated channels had become overwhelming and he’d had the intuition that continuing to pressure the company as hard as he could was increasingly looking like flogging a dead horse – which is why he went looking for a lean sensei.

In their early gemba walks together, the sensei went to look at: 1) the customer front end (can we visualize the website as a conversation with customers?), 2) the supply chain (how can we guarantee the right car for the right customer at the right time?), and 3) purchasing (how do we procure cars for the online catalogue so that customers find the car they want at the right price – and the company still makes a little bit of money?).

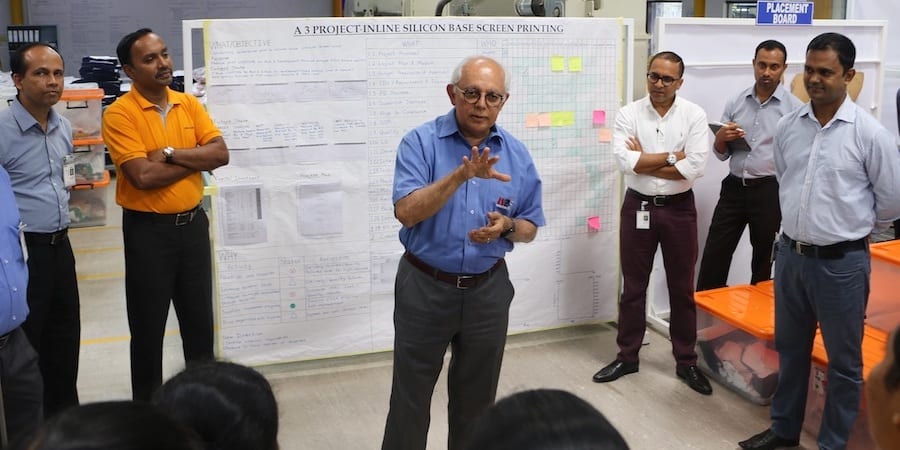

Beyond arguing for greater visualization, all the sensei did in practice was teach the basics of the Toyota Production System and of structured problem solving for front-line teams. Nothing more.

The CEO embarked on a regimen of frequent, regular gemba walks, from the sales points to head office departments, and brought his executive team committee together to share how each department head solved specific problems and how this impacted other functions. This, essentially, led to stopping some doubtful projects and focusing more on making work the existing infrastructure and focusing on interfaces. No reorganizations, no concentrations, no platform changes, or any other major change for that matter.

The difficulty in explaining how lean really works can be illustrated by asking both the CEO and sensei what they actually did:

- The CEO changed his management method from looking for the right solutions and pushing for implementation and then solving issues that came up to developing people by challenging them, giving them exercises to solve and listening intently to what they had to say, showing respect and support. Challenge, exercises, respect.

- The sensei helped implementing pull and problem solving in every department – which is easy in some cases (such as logistics) and hard in other (such as data science) – and turning the chain of command into a chain of help. Pull, stop at defect, kaizen.

The answer is neither completely organizational (pull system and chain of help), neither completely managerial (challenge, kaizen exercises, show respect). It is both. In fact, both aspects have been present all along in Toyota’s own description of what it did, from the original paper in 1977 that outlined the Just-in-time system (only the necessary products, at the necessary time, in the necessary quantity) and the respect-for-human system (workers are allowed to display in full their capabilities through active participation in running and improving their own workshops). To a large extent we can see in the CEO and sensei’s perspectives two essential dimensions of lean:

The secret sauce is that you need to do both: organizational solutions require a different managerial approach to succeed, the managerial approach requires the organization of systematic visualization and problem solving to be effective.

The lean approach to organizational change is exercises, not implementation. These organization exercises immediately surface development problems. For instance, on the supply chain front, the simplest exercise in the book is to identify parking spaces. Logistics is a matter of moving objects from one specific place to another specific place at a specific time, so the starting point of any pull system is to identify space. In AramisAuto’s case, this meant identifying visually every parking slot.

Although this sounds trivial, this very simple activity immediately revealed many issues. Some sales points did it right away. Some didn’t see the point and couldn’t be bothered. Some hit apparently intractable obstacles and explained it could not be done. Juliette Dumas and Cyril Gras, in charge of the kaizen office, had to coach and support all team leaders to help them get it done.

Visualizing parking spots wall-to-wall in AramisAuto didn’t happen through the roll-out of a “visualization program”, but by spill-over, convincing one team leader after next of:

- The intent of the company to pull cars in order to respect customer appointments;

- The purpose of visualization in pulling cars;

- Problem finding by recognizing typical obstacles they were likely to meet;

- Problem solving, and being curious about how other sales point leaders had solved these problems;

- Standardizing so that visualization can be respected by the team and maintained on the long run.

This is a development process. The team leader progresses, on the issue of visualization, through the usual developmental four steps of:

- Unconscious incompetence: not knowing or caring about the importance of visualizing every parking spot;

- Conscious incompetence: realizing that this was important to support the company in its attempt to improve respect of customer appointments;

- Unconscious competence: learning to do it from doing it, without really understanding the ins and outs of the activity, nor the deeper logic;

- Conscious competence: understanding parking visualization, its issues, its typical solutions, knowing who does what how and its theoretical importance to running a sales point – in order to be able to teach others.

The next exercise proved to be harder: giving transport trucks appointments as opposed to ranges. As the joke goes, when a transport tells you “I’ll deliver between 8:00 and noon,” the answer is “Fine, I live between London and Bristol.” The idea was to reduce time imprecision to control lead-time – an organizational improvement. But here again it immediately became a developmental challenge as the central logistics team firmly believed “you can’t control transport” and spent all its time in workarounds.

The difficult trick to lean is to learn to turn the wheel of managerial-to-organizational (any managerial challenge needs visualization and clarification through 5S and kaizen exercises to change the process) and organizational-to-managerial (any organizational or process change needs problem solving and further kaizen and suggestions to be sustainable).

This two-step engine is part of what makes lean so effective, so easy to grasp on the gemba and so difficult to explain in generalities. We’re always moving from process improvement (change something in how work is organized) into people development (learning to cope with the new process in all conditions) to process improvement (changing a further step), etc. with the intent of increasing customers satisfaction by increasing value (adding quality, reducing costs) and developing people capabilities.

It's therefore important to keep in mind the dual nature of lean:

The real “transformation” lies not in making processes more efficient – after all, Taylorism has been doing that for over a century. But neither does it lie in changing the management style to listen more and direct less in order to encourage initiative – again, these recommendations have been around since the late 19th century. The unique transformational idea of lean is learning to do both by fluidly moving from one to the other.

As our thinking is deeply conditioned by functional specialization, lean narratives tend to fall into either “hard” industrial engineering (apply the lean tools to fix the process and make it perform better) or “soft” human resources (become a better manager by taking better care of your people and giving them space for initiative and growth). We now know that “soft” people development without “hard” progress on pull systems and chain of help just adds to the confusion, as people follow their own insights and initiatives without the compass of customers satisfaction and teamwork across functions. We also know that implementing lean to improve processes leaves people befuddled and unengaged and doesn’t deliver beyond low-hanging fruit (and indeed, this is still an issue for AramisAuto, with many people in the company feeling they haven’t been explained “lean” well enough). To truly grasp lean and realize its promise we need to make the mental effort of going beyond these arbitrary differences and seeing the system as a whole – a blend of both process organization and human psychology.

The deeper lesson of seeing this two-step engine at work is realizing that the strength of a company relies on individual participation in the process of creating value. Each person in front of a customer, or fixing a car, or delivering a truck is the most important person in the company. There is no way around it. Any person in difficulty puts the entire company in difficulty. In order to get participation, we need, first, a clearer process so people see where they can participate and, second, supportive management that understands that participation is the magic sauce, as opposed to making people comply to instructions, rules, and management demands. Making better products does start with developing people, as Toyota has taught us. But to develop people, we also need clearer processes.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

INTERVIEW – Prior to his talk at this year’s Lean Transformation Summit, the CEO of a large apparel manufacturer tells us about the company’s lean journey, and its impact on Sri Lankan society.

FEATURE – Riverview Gardens in an NGO striving to build prosperity for the community around it through capability development. The authors suggest this should be the goal for the lean community as a whole.

INTERVIEW – This agro-industrial business in Colombia is applying lean thinking to its harvesting process. The harvest manager explains the difficulties and opportunities encountered on the journey so far.

FEATURE – What is psychological safety? What is it not? This article explores its advantages and foundational elements, and how organizations need to transform their leadership to achieve this evolution in management.