Womack on overcoming employee resistance to lean thinking

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - Every practitioner has encountered employee resistance to lean at some point. Here's a few tips on how to win over naysayers and perhaps even turn them into some of your biggest supporters.

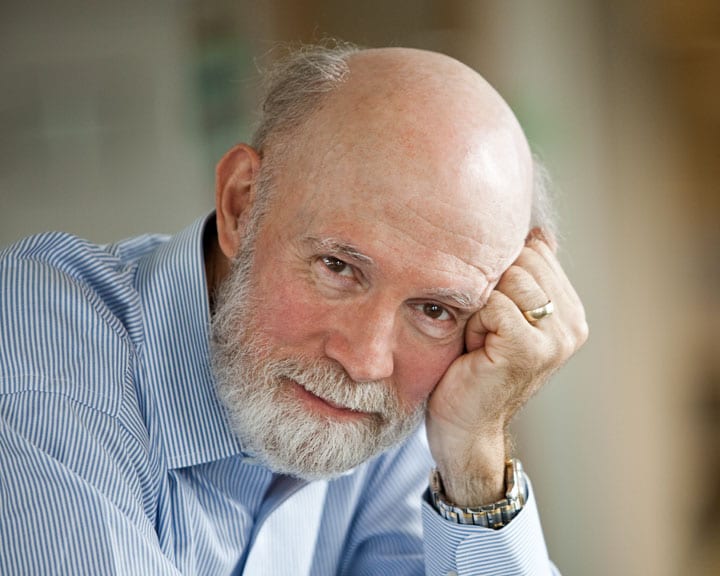

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

After my presentation at the recent LEI summit in New Orleans I got a question from the audience that I have heard many times in the past. "What do I do about the anchor draggers in my organization, the people who seem to build up barriers to every aspect of our pursuit of lean enterprise no matter how hard I try to convince them?"

In the past 25 years, since the publication of The Machine That Changed the World, I have become an expert - perhaps even a "world class" expert? - on countermeasures for anchor draggers, so let me share what I have learned.

First, I try to assume that anchor draggers are good people with good intentions. As humans, our default idea is that the root cause of the anchor dragger problem is that these are bad people. But this is the biggest barrier to creatively engaging them. (It's a case of jumping to the "one who" rather than asking the "five whys".)

So I proceed by asking why they are dragging the anchor on efforts to implement lean tools and lean thinking. When I do this (and it usually doesn't require five whys to get to the root cause) I usually find that their resistance is based on one of two perceptions and often both.

The first is that the proposed lean methods and the accompanying lean management system won't work and will actually harm the organization. The second is that they will personally be harmed if the new methods and thinking are applied. And it is certainly not foolish or bad behavior for the so-called "anchor draggers" to resist new ideas if these are the perceived consequences.

So how do I engage them to address these perceived problems?

For the first perception, I propose experiments that are bounded and which can give rapid answers as to whether the proposed new ideas will actually work and benefit the organization. I encountered a recent example in an effort to introduce lean thinking in a large retail organization. I tried to make the case that by reducing inventories in stores, with frequent replenishment of stocks in small quantities, it would be possible to free up large amounts of cash while also reducing out-of-stocks (e.g. times that there are not enough of a given item on the shelves to satisfy customer demand.) I presented some lovely logic (or so I thought) about how lean replenishment with leveled ordering could produce this result. But my audience of managers, with long careers in the industry, simply couldn't believe this could be right. Their whole work experience had confirmed the obvious truth that lower inventories could only be obtained by tolerating higher out-of-stocks.

So we found one small, isolated part of the company, in a niche market within the industry, and conducted some rapid experiments with level ordering, more frequent replenishment, and lower inventories on the shelves. (My argument for doing this was simple: "Even if this small experiment is a total failure it won't do any significant damage; so let's just try it right now.") To their amazement (and, I must confess, to my relief) we found that inventories can be reduced substantially while out-of-stocks also fall substantially.

Even this finding wasn't enough to convince everyone, even in this small business unit. So the argument moved to a new level: "Sure you can reduce inventories and out of stocks with lean replenishment. Everyone knows that. But there is a big cost penalty in the large increase in transportation costs. So lean methods are really not worth the effort in terms of business results." In response I proposed more, bounded experiments to see what actually happened to transportation costs. (Answer: By proper use of milk runs they stay about the same.) That was the end of the anchor draggers in the small business unit conducting the experiments.

But, of course, the argument moved again, now to the level of the bigger organization. "Sure. Those ideas work in this small business but they could never work at the larger scale of the core business where I manage." My answer: "You may well be right and I don't doubt the sincerity of your objections. But could we just try some rapid, bounded experiments in the big organization and then adjust our expectations about lean methods to the results of the experiments?" Bigger experiments take time but I remain confident that the number of anchor draggers steadily declines as the number of experiments increases.

This all sounds simple enough, but what about the second perception, that employees will be harmed by the implementation of lean methods and management? Engaging employees on this perception is both easier and harder. The fear that "lean is mean" in the sense of slashing jobs can be addressed easily by senior management. They simply need to say, "Our efforts to create a lean enterprise will not cost anyone their job." And they must walk their talk.

A harder aspect of this perception is the belief that applying many lean methods, perhaps standardized work in particular, will strip away hard-earned, private knowledge about how to perform tasks and make employees vulnerable to termination for other reasons or to a reduction in grade as the work is simplified.

I try to engage employees on this perception by asking how much of their current activities are avoidable waste that actually thwarts the ability of their organization to sustain employment and grow. And the answer is always, "A lot." "So," I say, "how about some experiments with standardizing your work so that your key skill becomes improving your work to eliminate waste rather than creating heroic workarounds using your secret knowledge to get the work done at all?"

Again, note that my focus is always on experiments to test hypotheses, not on citing some lean authority. (E.g., "Here's what Toyota does. You must to do it too!") The most important thing I've learned in the past 25 years about anchor draggers is that they can become some of the staunchest advocates for lean methods if you validate your lean hypotheses with simple experiments and if you speak directly to their doubts and fears.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – This article analyzes some of the most effective tools lean practitioners can deploy to design solid processes characterized by an effective sequence of tasks and a focus on customer value.

INTERVIEW - Pierre Masai, CIO of Toyota Motor Europe, discusses IT across the company's operations in Europe, highlighting the importance of people engagement and experiments.

FEATURE – Hoshin is a powerful management practice that aligns the work at different levels to a company’s strategic goals. The author offers a one-page visual summary.

INTERVIEW – In a chat with our editor, Priya Lakhani explains how technology can be used to understand a student’s unique learning pathway and design teaching accordingly.