Follow the gemba walk in a SNCF train maintenance center

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA - We follow the author on a visit to a train maintenance center in France. Through practical examples and pictures from the gemba, she explains how the center is transforming itself.

Words : Catherine Chabiron, lean coach and member of the Institut Lean France

With so many strikes making the headlines, foreigners may have construed a poor image of the French railways over the years. In France, we tend to have mixed feelings about SNCF: we always go between "No, not again" when problems occur and "Wow" as we recognize the company is working hard to improve timeliness and provide better customer support at peak times (as well as the significant investment on high-speed trains they have made).

What most people don't know is that lean thinking is at work behind the scenes at SNCF.

I recently visited one of the country's 39 technical maintenance plants, in Lyon. Boris Evesque has been the director of the plant for four years. Four hundred employees work in three shifts (an important part of the maintenance of trains takes place at night). They are responsible for maintaining, cleaning, and repairing 30 trains, and delivering them back to commercial service.

Before they started going to the gemba and adopted kaizen as their main improvement tool, Boris and his team went through a period of fruitless discussions in meeting rooms and quality audits of their sub-contractors. This is a common example of traditional management: following the audit, you list down what’s wrong (like fingerprints on train windows) and charge the sub-contractor a penalty accordingly, which in practice eats up any margin they may have left on the contract. In the end, because nothing improves, the auditors no longer see the value in their work. In the meantime, the sub-contractor is at a complete loss over what to do and simply pays the penalty. Imagine the monthly contract reviews!

Boris decided to turn to lean about 18 months ago, and secured the help of a sensei. This clearly started a new approach :

- Strategy (“What are the key focus points we want to work on?”)

- Gemba focus (“Let’s try and understand how we can create a safe working environment and have trains delivered on time?)

- Kaizen (“How could we do this better, faster or with less scrap or waste?”).

Boris told me: “Performance will improve if we manage to develop our people’s capabilities to work on the trains, with all the associated technologies or know-how. This approach yields far better results than trying to force discipline onto people or ‘create a brilliant system’.”

And indeed, as we walked along the vast workshops, Boris showed me a lot of kaizen ideas that have been devised and implemented by the maintenance teams. These focus on trains, specific parts or maintenance jobs, and contribute to improving the overall work environment. Here’s a few examples:

- A cart designed to lift all the tools needed to work on a pantograph (the jointed framework conveying a current to the train from overhead wires) to the top of a train.

- Colored containers to ensure the right fluid is used on the right trains in the right quantity (an error with the fluid is the equivalent of putting diesel in your car instead of gasoline – you will need to pump it all out and start all over again).

- A very clever device that checks the alignment of two critical silent blocks on the car coupling equipment. The previous system took a lot of time and was very unreliable: poor coupling between two cars could cause jolts and discomfort for passengers and even delays, as the countermeasure is to reduce the speed. Of course, it also means more trains are brought back for unplanned maintenance.

- A kit (consisting of a bicycle pump, fishermen hooks and a garden canvas bag) assembled at low cost but very effective in carrying out the messy (and rather unpleasant) job of extracting the toilet pumps in the train.

There was no fancy idea management system on the walls – those that tend to focus on numbers and trends, rather than on the actual content – but, as I walked around, improvements that make the work easier and limit delays seemed to pop up all over the plant.

- As flat storage is not yet implemented and high racks are still a common storage solution, two different teams have put together devices that let them see what is inside the crates placed on the higher racks, without having to lower them down – one removes the front panel and replaces it with a net of strings, while the other consists of mirrors placed above the crates. Needless to say, the next improvement they are planning for is flat storage.

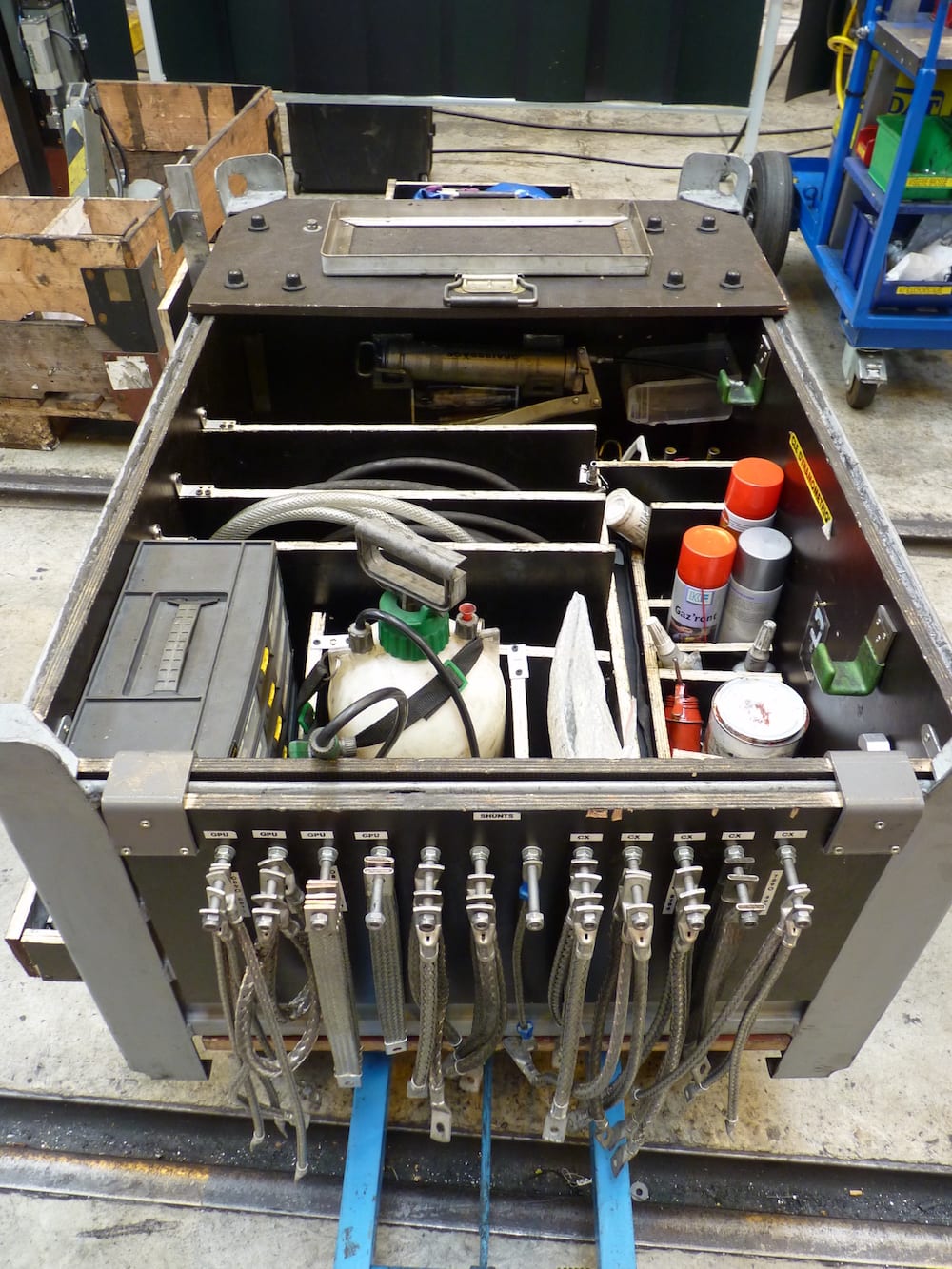

- SMED is being implemented on the bogies – those 7-ton frames and wheelsets you see under the train cars. Previously, once a bogie had been maintained, they would fit it back on the car, plug in all the transmission hoses, and test the sealing. In the unfortunate event of one of those tests failing, you would have to keep the train for another four hours to unplug and unscrew everything, get it all out, check and repair, and fit it all over again. Since SMED was introduced, the sealing tests are conducted ahead of the bogie fitting using small testing kits specifically designed by the plant’s technicians.

None of the above kaizens saw the involvement of the plant managers, who simply created the conditions for the improvements to happen (by focusing clearly on what needed to improve – schedule, quality, attention to the work environment, ergonomy, and support in terms of allocated time and resources). Boris totally changed his management routines and now spends almost his entire morning on the shop floor (paying particular attention to the daily management brief and to late train deliveries, and visiting one team area each day). This is how he described his new method : “These days I ensure we agree on the problem and then let people work on it without interfering. Instead, I support them and come back to ask for updates.” Boris is also coaching his direct reports and maintains a schedule whereby each of them has to present progress on an A3 and an improvement project they have been working on.

Boris and his team also worked with sub-contractors. With one of them – the cleaning company – they have built a dojo to clarify cleaning standards and provide regular training to cleaning operators. They expect this experiment to gain momentum.

So, is this maintenance center transformed yet? In part it is, but there are still numerous improvements that need to be made. Boris is well aware of what needs to happen next:

- Use 5S to eliminate unused tools or components, and facilitate flow;

- Implement a small train that delivers only what is needed and therefore reduces the stock built up by the ERP system with its inadequate packaging, wrong minimum inventory or faulty master data;

- Create train preparation areas to tackle late train delivery at the gemba, rather than on Excel files;

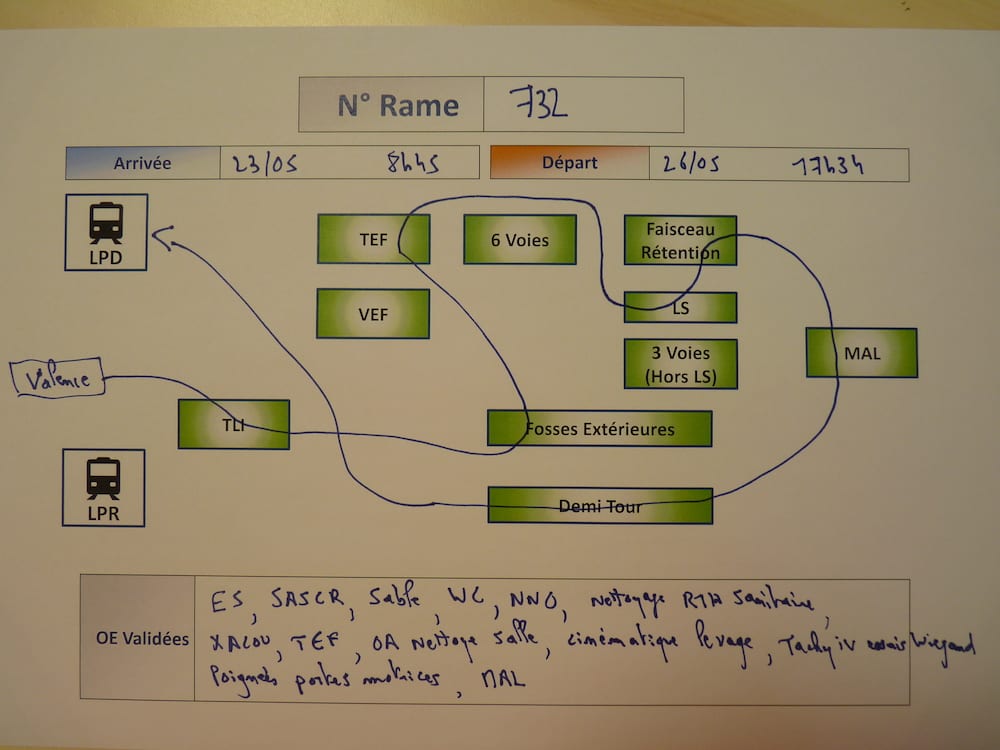

- Optimize flow: trains may be big, but it is batches, excessive stocks, specialized production units and a confusing layout that make the space seem too limited. The huge spaghetti (in the image below) that represents a 200-meter train moving from a work station to another is mainly caused by the use of production units that specialize in single tasks (like external cleaning, internal cleaning, repair, extraction of huge components such as bogies, etc). An increased focus in polyvalence and multifunctionality would reduce motion, and the overall lead-time with it.

THE ACHIEVEMENTS

There may still ground to cover, but the results are already visible and confirm that the mindset at the center is changing, less than two years after lean was first introduced.

In two years, the number of train breakdowns has been halved (when the center is exclusively responsible for their maintenance), late deliveries have been reduced by 75% and workplace injuries are down by around 65%. Lastly, the work on each train brought in for maintenance has increased by 12% in two years, which means there is one more train fully available for commercial service every year.

Perhaps more importantly, several operators have told their managers that see them as being more “on top of their real problems” – and believe me, in an industry as heavily unionized as the French railways, this is clearly a compliment.

As our gemba walk drew to an end, I found myself reflecting on the work being done at the maintenance center. Two things really struck me, and I believe they are both testament to the growing autonomy of the teams:

- The first prototype for the small train that delivers parts and tools (it was an old joke in the center, as it was discussed many times but never implemented) was created this summer while Boris was on holiday, under the leadership of the logistics team.

- There seems to be an increased interest in (and understanding of) how the work of each team influences the overall performance of the product (in this case, a train). We walked past a large board that carries the problems encountered on each train and, in front of them, we saw two teams (the electrical and mechanical teams) deep in discussion over causes and effects. The next step will be to open the exchange to maintenance engineers.

It is clear that a lean culture is taking roots at this train maintenance center. And it is beautiful to see!

THE AUTHOR

Read more

CASE STUDY - Faced with high costs, low demand and growing competition from China, Turkish textile manufacturer Yesim managed to develop a competitive advantage by transforming its ways with lean thinking and increasing its focus on the customer

FEATURE – We tend to take the “goodness” of lean for granted, but – the author says – we should stop and think about what makes lean a good business practice. Why is it a way of thinking all businesses should adopt?

FEATURE – To make the right decisions, the contribution of the team and the leader’s intuition are not enough. It’s also critical to identify the most effective channels and activities for your marketing activities.

CASE STUDY – An Australian university has been applying lean to streamline and improve its processes, discovering along the way how big a change the methodology can affect in the organization's culture.