The incredible lean turnaround of an engineering department

FEATURE – A French automotive supplier has been applying lean principles to transform its engineering department with great results. In the process, they have realized they could put in place a really effective system to build innovation.

Words: Stéphane Moreau, Engineering Director, and Frédéric Masson, Product Development Manager, Advanced Comfort Systems (ACS, a company of CIE group)

ACS first encountered lean thinking around 10 years ago, when the methodology – or, rather, its toolbox – was introduced in the manufacturing department (we design, engineer and produce shading and glazing products, and more recently we have added opening glass roofs to our portfolio).

Back then we achieved a few results in assembly as managers in various plants tried to implement the new system, but failed to understand that lean is more than just a few tools that you force-feed an organization. We hadn’t focused on developing the learning capabilities of our people, and before too long our results proved unsustainable.

In 2012, one of our plant managers came back from a training session in Lyon with a better understanding of what lean really is. We then initiated a few experiments and organized training for our people, which led to a number of noticeable improvements.

When Michael Ballé came to visit us (he often coaches us), he made a suggestion that changed the course of our lean transformation and offered us the opportunity to look at it from a different perspective. He explained that if we wanted to be a fully lean organization we could not shy away from applying those principles to product development right away. Variation in our designs was costing us quite a lot of money, which made Michael’s proposition particularly interesting.

However, we thought it could be a risk to bring change to our 75-people Engineering Department right away without a sensei coaching us. We wanted a better understanding of lean before we delved into this new mission, and decided to attend a course that would help us get there.

Around a year later, we felt we were ready. We pitched our idea to the President, and we all agreed it was time to proceed.

That was a key learning for us: getting top management to understand how valuable lean is and helping them to see that the time spent on lean is a sound investment is a turning point in any transformation.

THE POWER OF THE OBEYA

The first thing we did was placing an obeya room right in the middle of the Engineering Department. With the 10-15 projects we manage each year, it made sense to have a place where we could gather all the technical and processing information we needed for each of them. Yet, our implementation of the obeya had two phases, and the first phase was basically a form of glorified project management: at the beginning, we only involved the delivery managers, to track the delivery of each project. This was a conscious decision, as we saw this as a good – if not very “kosher” – way to gradually introduce lean in the department and to get people from each team in the same place at the same time every day. This first phase lasted six months.

After that initial period, during which we had created a sort of ritual, we were ready to run the obeya by the book and initiate the second phase. Therefore, we introduced new boards that listed the technical issues each project was facing – this was for the learning of our engineers.

For each project we analyzed and tracked in the obeya we decided to focus on the five biggest issues, trying to find their root-causes.

This was a new way to find solutions for us, a new philosophy, which in time helped us to combine the expertise of our people and encouraged them to work together on tackling problems. Before lean came, our engineers tended to jump to solutions – trying to fix problems directly on CAD – without having a proper understanding of the problem at hand, which often led to stress and quality issues. These days, our main projects are run from the obeya (in fact, we have two obeyas – one for managing projects and one for target costing).

THE NEXT STEP: TARGET COSTING

Whenever you are called to design a new product, you receive quality specifications from the car manufacturer and you need to get back to them with a technical solution that meets those specifications and with a quote within six months.

In the past, the ACS sales manager passed customer requirements along to the product development team, who built the architecture of the product and then transferred it to the processing department, which defined the assembly process accordingly. From there, the data travelled back to the sales manager, who came up with the price the company would offer the customer – who would often deem it too high or complain that the specifications were not in line with their needs. We used to have several loops, which wasted a lot of time and resources.

Communication among departments was clearly not working, and when we realized that we decided to add a second obeya, in which we would work on target costing.

Our new system hinges on two target-costing meetings per week, in which representatives from Processing, Engineering, Quality and Sales participate. When we receive specifications from a customer, we now ask the sales manager to provide a target cost and our engineers to define a standard architecture (in line with the target cost) that we can put forward.

Identifying the price our customers are willing to pay and building our work around it is one of the main lessons of lean thinking, but doing it does require you to find ways to adjust your own costs. How do we do it? During our target-costing meetings our engineers identify potential “flexible areas”, technical specifications of the product that we can play around with – for example, new components in the glass that impact its thickness or the way we work with a supplier – in order to get enough flexibility to adjust our production costs. After one or two weeks of technical validation, everybody meets again to approve the inclusion of the flexible solution in the final offer. The introduction of this method had significantly decreased the number of loops we go through.

A second step in our use of target costing entailed changing the way in which we flag up and define technical problems: we no longer have a dedicated team doing it, but we have brought every department together (engineering, processing, quality and sales) so that their experiences and understanding of the problem can be combined.

GOING THE EXTRA MILE FOR THE CUSTOMER

We didn’t stop at target costing. In the second obeya we also introduced a Customer Wall as a new way of really trying to understand our customers. The reasoning behind it was that we receive the same specifications as our competitors and we needed to find something that would differentiate us from them and allow us to go that extra mile for our customers.

This was the result of another important lesson we learned from lean: one should never be afraid of trying new things, an idea that lies at the heart of experimentation and kaizen.

These days, we make an extra effort to understand what each of our customers expects from our products, besides the technical specifications they communicate to us. This new approach has led us to study our customers’ own customers, so that we can suggest certain changes and extra features to the products (even when we are not asked to do so) that we think end users would find of value.

We began by organizing half-day meetings with car manufacturers, salespeople, technicians and end users at our customers’ office (but we also interact with car dealers around 10 times a year), doing blind tests and observing people’s response to our products. It is interesting to see how we now focus on things that in the past we would have paid very little attention to and that now have become essential to the design of our products.

Today, ACS is no longer just a sub-contractor to its customers: we have become their partners, with an increased understanding of their needs and an interest in actively participating in the creation of products that will delight end users.

It took a while to get here. When we built our first Customer Wall, it was only the two of us working on it. This actually reflects our overall approach to the application of lean to engineering: we didn’t want to impose the philosophy on our people and thought it would be better to gradually involve them as we showed the results of our experiments. Once they started to get involved and try out the new system, they gladly got on board.

With other initiatives – especially those that, like target costing, call for the involvement of professionals from different ACS departments – we encountered more resistance. The first response to the target-costing obeya was skepticism. In time, however, our people realized that joining this meeting would enable everyone to gain a good understanding of the work and to stay in line with customer needs. Having everybody in the same room means that information travels fast, that communication improves and that job satisfaction increases. The system only works as long as this exchange takes place.

It wasn’t always like this. When we first introduced the obeya meetings, we had to be there all the time to ensure people would attend. For a few months, they would do it for a while and then slip back to the old system, thinking that skipping a meeting wouldn’t be the end of the world. Lean is a matter of discipline, but once the new and better way of working becomes engrained in people’s minds you quickly start seeing them take it on with enthusiasm and without being prompted.

So here’s another important learning for us: sticking to the standard is critical – even when people argue it isn’t – because there is a clear correlation between teaching them the lean way of working and customer satisfaction.

Make no mistakes, however: discipline doesn’t mean to blindly force people to follow a standard in the way they collect, gather and communicate information in the obeya. While adherence to standards is definitely necessary in several instances, we try to not be too prescriptive: sometimes it is ok to document a problem, solution or simple piece of information in a more traditional way.

SLOW BUILD FOR BUILT-IN QUALITY

Our most recent experiment is Slow Build, an activity that aims to boost collaboration and information sharing between the design department and production operators.

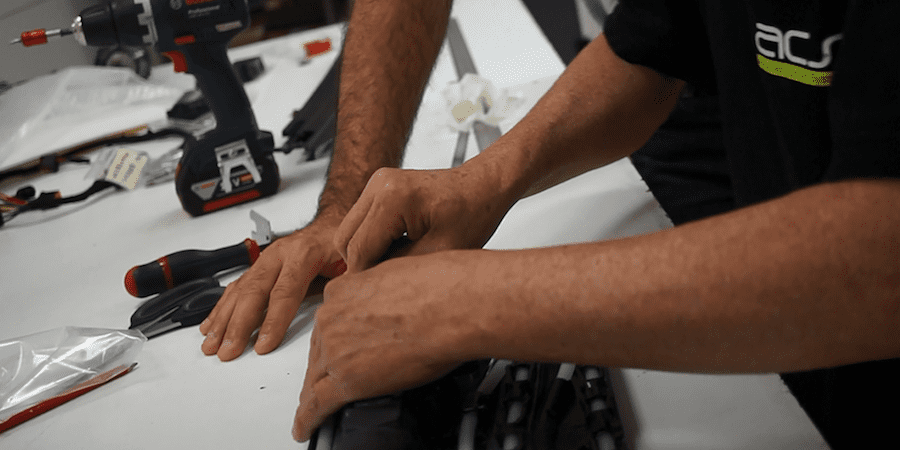

As we build the architecture identified by the designers on the Customer Wall, we use a 3D printer to create a prototype of each component. We then place all the 3D-printed parts on a table and invite production operations to assemble the product in the way that makes most sense to them.

Because we film them while they do it, we can easily identify the best and most efficient way to assemble a product – which we can share with the process engineers so that they can adapt the assembly line to the new work sequence. This is also the best time to find technical issues in our products (like a bad contact or an abnormally large gap between two parts), which we can therefore fix quickly and cheaply before the actual product is manufactured. Naturally, this greatly diminishes the risk of quality problems.

Using Slow Build means that we are now building quality in from the very beginning, rather than relying on quality checks and on expensive rework at the end of a project. Creating this synergy between designers and operators was one of the most important developments in our lean journey.

BRIDGE-BUILDING TO FUEL OUR TRANSFORMATION

Slow Build is a great example of our efforts to build bridges within ACS. As we mentioned earlier, there are huge benefits to reap from an increased level of collaboration among professionals working in different departments of the company.

The first step in this direction – and one of the most noticeable changes in our department – was recognizing the expertise of others and understanding how this allows us to get closer to our customers. Our engineers no longer spend all of their time at their computers: they have now realized that the product they design will be assembled by one of their actual colleagues and fitted on an actual car that will he driven by an actual user.

In our minds technical expertise is more than just making the best products; it also means that we need to become more aware of the roles of other people involved in the value stream and of the needs of our customers.

We see this at play all the time these days, which is of course a result of our lean efforts. Whenever a quality issue occurs and a defective part is returned to us, for instance, we have started to involve an engineer – and not just the quality professional – to really understand the root-cause of the problem and fix it as soon as possible. In the past, a defective part was often dismissed as a small problem in the grand scheme of things, whereas now we have realized we can learn a lot from each and every one of the problems we experience and the mistakes we make.

A TAKT-TIME FOR INNOVATION

As an organization, we feel we have build many innovative products over the years, but in the past innovation for us would occur when the opportunity arose, almost by chance. Since the introduction of lean in our engineering function, however, we have been able to create a process for it.

We follow an actual takt time for innovation: each year, a dedicated team comes up with a specific number of improvements in the products we already have and with a specific number of new solutions – it’s where traditional R&D and kaizen meet. Our improved development plan has revolutionized our approach to innovation (the information Marketing can gather only goes so far): we use the technical information we have learned to efficiently gather in our obeya to define our future development strategy.

There is a lot of talk about innovation in this world, and there is no doubt that in this day and age no organization can hope to survive without it. We believe that, thanks to the system for learning together it allowed us to put in place, lean thinking is acting as an enabler for innovation at ACS.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – A lean coach from Argentina reflects on the transformations he has supported across Latin America and on why lean can help unlock the potential of the continent.

FEATURE – The Covid-19 pandemic has reminded us all that the nature of the work has changed forever. The author discusses remote work and how Lean Thinking can help you make the most of it.

INTERVIEW – Lean is not widespread in Colombia’s construction industry yet. The interviewee discusses the benefits this philosophy can bring to construction sites.

FEATURE – The author discusses how the hoshin kanri process, coupled with effective coaching, helps us to tackle the challenges inherent to implementing change.