Starting out with lean thinking? Refer to the original TPS

FEATURE – Starting off a lean journey is no easy feat, and existing models won’t tell you what the next steps are. That’s why you should go back to basics and let the Toyota Production System “house” from the mid-1980s show you the way.

Words: Michael Ballé and Boris Evesque

How can we start with lean in a new environment? This is a frequent question, and one that is not easy to answer, as there are no known “entry hacks” into lean thinking – one must adopt it, which can only happen through practice. Yet, the question remains…

This is the situation we found ourselves in about a year ago, when one of us (Boris) decided to apply lean to his operations in earnest. As director of a train maintenance center, he understood maintenance inside out, was encouraged by his management to adopt lean practices and had read the literature. The other author (Michael) was familiar with lean practice but had never seen a train maintenance center – and therefore had no a priori idea on how to go about “leaning” one.

Lean, we believe, is our response to Toyota’s challenge of creating vastly superior organizations both in terms of value to customers (and society), performance and relationships with stakeholders. Toyota teaches us that in creating value (more varied, better products and services) we unavoidably generate waste (financial, social and environmental), but that by learning to “think lean” we can eliminate some of the deep-seeded causes of such waste. So far so good, but how can we do it in practice?

There are many great descriptions of what lean is. Jim Womack and Dan Jones’ original five principles of lean thinking, of course, but also Jeff Liker’s 14 principles of the Toyota Way, or Mike Rother’s Toyota Kata, all the way to the latest, the Lean Global Network’s Lean Transformation Framework. Each of these models are both right and insightful, and are always very useful in shedding some light on the “mystery of lean” by looking at it from the process, culture, neuroscience or cognitive heuristic perspectives. They’re great at giving an overall perspective, but not that helpful when it comes to telling practitioners “what to do next”.

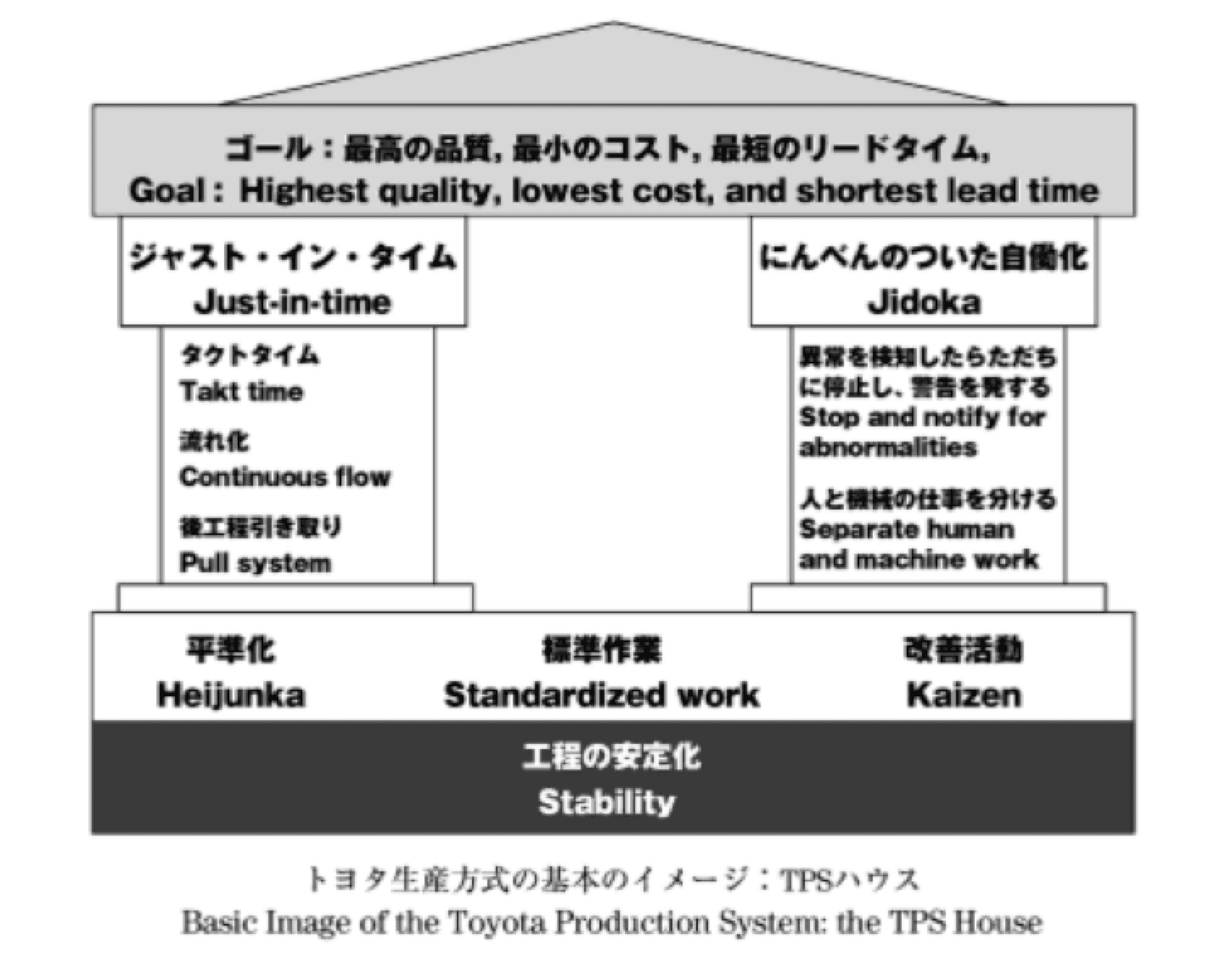

Which is how we found ourselves returning to Toyota’s own description of the system from the mid-1980s (not the Toyota Way that came after 2001, but the original Toyota Production System “house”), as captured here by John Shook and Toshiko Narusawa in Kaizen Express:

Toyota formulated this Toyota Production System “house” at a time when it was trying to spread TPS thinking both within the company and to its suppliers by showing their top management how to fit into the extended just-in-time supply chain. At first glance, this model may look a bit alien, but it is actually very useful to clarify the next steps. Like a compass that points us in the right direction, the TPS house operates on three levels:

- GOALS: it defines quite clearly what goals we should be pursuing, starting with highest quality, lowest cost, and shortest lead-time (we would add safest operations and increased energy performance to account for evolutions since the mid-1980s). The goals are not levels to reach, but they ask the important question of our efforts’ dynamic targets: Where will we find quality improvements? Where will we find safety improvements? Where will we find cost reductions? Where will we find lead-time shortening? Where will we find energy performance increases?

- ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK: the second level of the TPS house shows quite specifically how to look at operations to achieve the stated goals: we want to simultaneously improve both the level of just-in-time and of jidoka. This leads us to figure out what our current level of JIT and of jidoka is. What would it mean to improve both of these features of our operations?

- ACTIVITY PROGRAM: the third level of the house tells us how we should go about it in practice. To achieve the goals of highest quality, lowest cost and shortest lead-time by increasing the levels of just-in-time and jidoka means that, in practice, we should ask the teams to conduct kaizen initiatives (studying their own work methods and improving them) and develop and deepen their work standards, and that we should look into how the work is planned to improve the level of heijunka (leveling in the sense of fractioning and mixing work as well as keeping it stable). To help teams achieve this, we should work with management to create the basic stability conditions (in terms of Manpower, Machines, Materials and Methods) to sustain kaizen.

With a little grey matter effort (well, a lot), the TPS house system supports us in clarifying what goals we should try to reach, why and how.

How did that play out in practice in our train maintenance center?

THE GOAL IS CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

How can we provide higher quality? This one is not rocket science. Passengers want to travel in comfort and reach their destination on time. With train maintenance, this translate into 1) having the train ready to go at the correct time, 2) making sure the train doesn’t break down during its journey, 3) that it’s clean, and 4) that all on-board equipment (like seats, doors, lights, flushes and running water) are in working order. In practice, we then asked ourselves what practical steps we could take to:

- Have the train ready a bit earlier than target to compensate for any last minute issue;

- Fix one concrete source of possible breakdowns;

- Better clean one aspect of the train;

- Take better care of one piece of customer equipment.

Tackling this pragmatically will not allow us to solve the systemic problem of train maintenance, but it did force us to face some tough issues and to focus on the next step rather than on the problem as a whole.

How can we provide better safety? This is always a difficult question because accidents are… accidental. Still, we started measuring consecutive days without accidents and listing safe vs. unsafe work habits, while asking both the Health and Safety department and all team leaders to conduct a daily audit on the shop floor to then be able to share findings all together.

This way: team leaders discuss with their teams during the daily briefing what to pay attention to and identify which standard they have to check today, while the Health and Safety department becomes aware of how to simplify the concrete application of standards for the teams.

Focusing day to day on safety issues made us confront the fact that train maintenance, by its very nature, deals with mixing humans and heavy machinery. We realized that proximity breeds familiarity and that we needed to remind people day in and day out of the dangerous situations they could find themselves in and not to get carried away just to “get the job done”, but try to stop and think when an operation seems dicey. Listing dangerous habits helped, but it is only scratching the surface of a more stubborn problem.

How can we lower the cost of maintenance? This is a question that has obviously been examined repeatedly before, and no obvious answer comes to mind except for taking into account the very size of trains – much of the working time is spent just going from one place to the other, which makes rework even costlier. With no clear objective in mind, we decided to look at the non-maintenance activities each technician had to perform (looking for parts, figuring out where the next place to work was, doing the paperwork) and wondered how could make that easier and less time consuming.

No easy answers here, but just asking the question opened up our eyes to the impact of capital productivity on human productivity – large spaces create lots of movement, and therefore costs – and made us wonder if there is a way to handle space differently.

Shortest lead-time: how can we reduce the time between when the train reaches the maintenance center and when it is released? This is a fascinating question because, obviously, the work content varies considerably depending on what needs to be done, from the 45 minutes needed to simply clean a train to up to the five days necessary to inspect and replace heavy machinery. Without a concrete idea of how to start reducing lead-time, we began to control it, setting up a large white board with the planned lead-time for each train and the overtime (if it happened), and committed to go and see with the management team to find the root causes of longer-than-expected work directly at the gemba.

The strength of the TPS house is that in a situation as complex and ambiguous as “improving train maintenance” it allowed us to move very quickly from puzzling over how to attack the problem to creating a shortlist of concrete actions:

- Control more tightly when the train is returned to the railway;

- Find one cause of breakdown to attack specifically, such as electrical connections;

- Focus on the cleaning of one area – we started with the train’s nose, the first thing passengers see when the trains approach the platform;

- Take better care of one piece of customer equipment;

- Control the lead-time train by train.

This practical shortlist gave us a way to start, as well as a way to explore which issues would be simple to solve and which would be less so, which in turn revealed (as it often happens) revealed deeper problems we had to tackle.

Clarifying these goals led us to set up an obeya room for the management team to meet regularly, track its own performance on these improvement goals and have a space to think and discuss away from the pressure of daily operations.

The benefits (as well as challenges) of creating time to stop and think about how to reach common goals and discuss (sometimes argue) as a team were both surprising and immediate” we built up teamwork and visibly accelerated the resolution of difficult problems as well as our ability to respond to the unavoidable crises that make train maintenance both so exciting and so stressful.

The first results came soon and were quite evident – the number of late deliveries of trains was cut by two and accidents by 2/3. Of course we know this represents nothing but low-hanging fruit, but we were quite surprised by the impact that getting the management team to own problems together and better work with their own teams on the ground made.

In terms of how t tackle the larger questions of higher quality, lower cost and shorter lead-time, the pillars of the TPS house also give very practical indications on how to handle the next steps.

GRASP THE SITUATION THROUGH JUST-IN-TIME AND JIDOKA

Takt Time: a rough calculation of takt time came to 50 minutes. Obviously, the delivery schedule is not organized like this: there are on average 30 trains to process every 24 hours, but with most deliveries in the morning between 4 am and 8 am and then again in the evening. Still, takt time allows us to break down the work in 50-minute units and encourages us to ask ourselves the question of how the center would work if a train had to be delivered precisely every 50 minutes (taking into account the variation of work content from 50 minutes to up to 7,200 minutes).

Continuous flow: with takt time in mind, we realized that the work on the trains was organized in batches. One employee, for example, runs through the entire train emptying all bins, followed by another with a vacuum cleaner, and so on. We started wondering how to organize a continuous flow of cleaning tasks one carriage at a time and then how many employees we would need to keep to the takt time. An immediate conclusion we reached when we started looking at the problem from this perspective is that quality is hard to maintain when one person has the responsibility for an isolated task on something as large as a train. By dividing the work carriage by carriage, responsibility can be taken for a completed piece of work, such as “one entire cleaned carriage”.

Pull systems: pull essentially means that we shouldn’t start on the next train until we’ve finished working on the current one. That is clearly impractical in the current organization but it also made us realize that there are about 10 to 20 trains immobilized in the center at any one time for a variety of reason: that’s a lot of capital just sitting there. Thinking about pull made us wonder why so many trains were idle in the center with either few or no technicians working on them and encouraged us to look differently at the planning process. Not surprisingly we discovered the plan was organized around the constraints and not around takt. To use John Shook’s phrase, we now need to make constraints our friends and rethink how work is pulled through the center.

Clearly, it’d be very easy to think that ideas such as takt time, continuous flow or pull systems simply don’t apply to train maintenance – the situation is too dissimilar from an automobile factory. Actually, just the opposite. Yes, the basic situation is very different but making an effort to apply just-in-time concepts to a new case, no matter how awkward it felt, led us right away to see things from a different perspective and to start envisioning the huge productivity potential that we couldn’t see before. The goals of the TPS house clarified where to start, and the first pillar showed us how to think about moving forward. It was similar with jidoka, as we wondered:

How can we stop and tackle abnormalities? Again, we can’t think of any immediate way to do this, but what we realized is how alone the technician is. All discussions occur in the office when the technician plans his work with his manager, and when they discuss the work done and fill in the paperwork. When something goes wrong in the train itself, however, the technician has to stop what he’s doing and return to the office to sort things out. The managerial process takes place away from the trains. This system amplifies considerably the waste of time each abnormality generates. The question we started asking ourselves was how to bring management closer to the trains and the operations. No easy answers so far, but a clear direction for improvement – and with huge impact on JIT as well. We made a first step by installing a paperboard on the gemba just in front of the trains with high work contents. On the paperboard, the schedule. Five times a day, team leaders come in front of the board to discuss the latest problems with the coordinator. This encourages to naturally face problems on the gemba when they occur instead of waiting for problems to reach the office. It is an important first step, even if we are still far away from an andon!

How can we separate human and machine work? This is a lesser-known aspect of jidoka, but one that is critical to creating continuous flow. The idea is that any operator should place the part in the machine, get it started with one touch and then move on to a next task while the machine does its job: the machine does not need human supervision to work and can stop itself when the work is not going as it should. Again, there seemed to be no obvious application of this concept in train maintenance center until we considered parts delivery to technicians. In the current system, logistics supplies “advanced” stocks where technicians come and help themselves to what they need when they need it. If we consider the supply system as a “machine” we can see that the supply system is dependent on the technician to work: the technician has to look for the right part, deal with missing parts, rummage around when something is missing and then return to his work station on the train. The idea is to bring everything to the technician where he is currently working to separate his work from the parts delivery work. We have no idea just as yet on how to achieve this, but our hunch is that traditional lean just-in-time techniques such as trains (yes, internal supply trains) can help. Further, we discovered that large parts of the work content of preventive operations are made up of tests and during these sequences, technicians wait on test benches: they connect the bench, they calibrate the bench, they press enter to confirm the end of a sequence and the beginning of the following. Their work is very mechanical and they are like an extension of the machine. Certainly we cannot change that snapping of the finger but we have just decided to make a first step: giving periodically technicians the list of the last equipment failures they are responsible for and asking them to have a critical look on the train with these information in order to:

- extend their work and their autonomy;

- show them that we clearly consider that they are not the extension of the machine.

This case shows quite vividly how the two pillars act as a system – in order to pull continuous flow work at takt time, we must separate the logistics supply work or the run of test benches from the technician’s work. For the logistic, we’ll do this by creating continuous pull flow in the parts supply system. For the tests, we’ll begin by opening the mind of technicians. In this typical case we can see how the two pillars build onto each other: you need both the right legs and the left legs to have a table.

As can be seen by this example, the TPS “house” frameworks leads one to ask very deliberate and specific questions of what next steps to take in order to improve even in environments as far as automotive production as can be, such as event organizing.

Furthermore, thinking through this framework immediately shows up glaring gaps in our lean practice, as well as how these various gaps fit together in the system and combine to slow down customer satisfaction improvements – for instance, how does improving our ability to stop and flag up abnormalities influence our takt time of presentations and vice versa?

The next question asked by the TPS house is: how are we going to solve these problems with the technicians themselves?

Kaizen: that part was the most familiar, as the train maintenance center had invested in continuous improvement for a couple of years, and the language was familiar. To clean up the approach a bit, we re-focused on Isao Kato and Art Smalley’s six-step kaizen to give a structured tool to team leaders to sustain improvement with their teams, favoring working conditions to start with, in order to show teams they could organize and run their own areas and take control of their own work. Recently, we began pointing kaizen closer to technical improvement potentials since “kaizen equals getting closer to the final process” (T. Harada).

Standardized work: on the other hand, standardized work stumped us from the start. How do you create standardized work with a takt time of 50 minutes? Before we started with standardized work, we looked into standard work. It wasn’t much of a surprise to confirm there were procedures for everything but precious few work standards. To initiate these conversations with the teams, we started working on individual problems solving with an emphasis on describing a problem as a gap to a standard. This pragmatic approach led us to discuss standard work in many varied circumstances and to engage team leaders and supervisors in writing down their first standards. Moreover, our beginning in technical kaizen is also a good start to write standard using step 2 of Kato and Smalley.

Heijunka: to achieve heijunka, all technicians would be perfectly multiskilled and go through a regular sequence of different operations. This is so far impossible in our current reality, and yet we can start looking into which operations we perform more frequently over a certain period of time and how we can better plan the sequence of operations to establish a more regular pace. For the first step, a simple heijunka board will show us the gap between our classical planning and a levelled one. Thus, heijunka will lead us step by step to rethink our planning to make work flow better and easier for the technicians themselves to envision sequences and handovers.

The foundation of the house is basic stability. In many areas we kicked off the kaizen process with zone control – asking the teams to use 5S to organize their work environment and make it easier to standardize operations. In doing this, we discovered how surprisingly unstable working conditions are – equipment is unevenly maintained and not always fit for use, the supply chain is spotty and our work methods full of ambiguity and open to interpretation. All in all, we’ve got work to do, but the gift of the TPS house is that now we know what works and have practical ideas of how to go about it. The rest is a matter of, well, work.

What, then, is different between the original TPS house model and others? Other models tend to go from generic to specific – they offer a full description of the lean approach that can then be applied to specific situations, in a deductive manner. The TPS house model, on the other hand, is specific-to-general. As we tried to show in describing how we discovered lean in train maintenance, the house points towards a next step, not a general solution. Actually, we’d better assume that we don’t know what shape the end solution will be but work, improvement by improvement, in the general direction given by the principles and discover the overall shape of the next stage as we get to it. It is a synthesis exercise, as opposed to a deductive one (to be fair, the “kata” approach can be used in both senses). One of the most fundamental changes in the train maintenance center guided by the TPS compass is that Boris and his management team stopped working towards process total overhauls decided in a meeting room (few years of suffering and tension) and began changing one step after the other, managing more and more from the gemba in a far calmer way.

The secret to lean learning, and a hard one to grasp, is to trust the TPS house and take the next step without imagining what the end solution will be (one reason we talk about countermeasures rather than solution). For Cartesian-trained engineers, this is harder than it seems as the temptation is always to try to get to a more optimized solution. The discipline the TPS house teaches us is to solve problems one by one as they appear, think of the next step in terms of where the “compass” takes us, but not imagine a global solution until it emerges from many observation points (beware of the law of small numbers – small samples can drastically bias conclusions) and in-depth discussions with all the professionals involved. We’ve realized that our challenge is not to discuss what we already know in common, but to access what each specialist knows that others don’t and get them to share this knowledge.

Insight results from using both the very high-level goal-directed thinking and the detailed ground-floor “just do it” one-step-at-a-time approach simultaneously. The model, of course, continues to evolve. Toyota has recently added “energy performance” to highest quality, lowest cost and shortest lead-time. This reflects the crazy long-term goal of phasing out internal combustion engines by 2050. Crazy high-level goals have always been part of the Toyota story. Indeed, Kiichiro Toyoda handed the baton to his cousin Eiji with the instruction to “catch up with America in three years.” It took a bit longer than that, but catch up they did. Similarly, the Prius came out of the intent to improve energy efficiency by 100%. Early proposals for 50% improvement were rejected as not bold enough.

Bold aims. Detailed work. This is why we return time and time again to the original TPS house, for its powerful inductive streak. Taken at face value, the house offers a great range of practical next steps to take in a kaizen manner without fully understanding where this leads, but with confidence we’re moving in the right direction. This is essential to practice the spirit of incompleteness and growth by doing and involving others, which is key to learning the deep metaphor of organic growth and changing our minds at a deeper level.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

INTERVIEW – We meet one of this year's Lean IT Summit speakers to hear about her team’s effective approach to turning Nordstrom’s IT leaders into coaches and truly supporting the firm's lean transformation.

FEATURE – Resilience and the ability to self-organize have been part of Ukrainian culture for centuries. Today, as the war continues, the country’s companies and resistance are tapping into those values.

FEATURE - Effectively dealing with a problem means learning to solve it in a variety of scenarios, not perfecting a point solution. For too long in lean we have only focused on gaining reusable knowledge... but what about reusable learning?

FEATURE – You have never seen a workshop like this before: Halfway Ngami in Botswana has creatively transformed car servicing and repairs by making problems visible and introducing flow.