Kaizen or kaikaku, wonders Jim Womack in his latest column

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN - Kaizen or kaikaku? This is the problem. When it comes to the pace of change, should we carry on with small, incremental improvements or aim at more revolutionary changes instead?

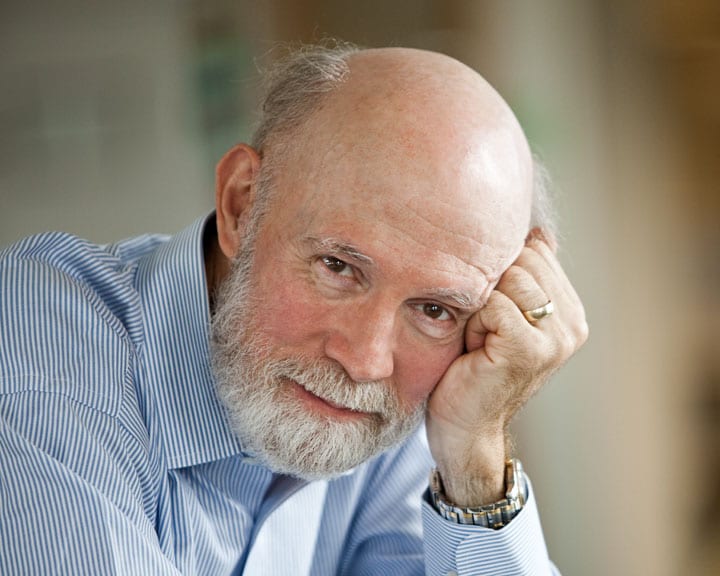

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

In the early 1990s, when Dan Jones and I were writing Lean Thinking, I heard about exciting lean experiments being conducted at Pratt and Whitney, the jet engine company in East Hartford, Connecticut. I was looking for example companies for the book from industries outside of the automotive sector where Toyota had set the first example. And Pratt was only a short drive from Boston. So I immediately made arrangements to visit.

What I found on the first of many visits was a remarkable example of what Pratt managers called kaikaku. (This is the Japanese word for revolution, in contrast with kaizen, which is incremental improvement or evolution.) In the prototyping shop for jet engine parts I discovered that over a few days the managers had moved every machine – hundreds of them, most not disturbed since the day they were installed – from process villages into flow cells for product families that incorporated many machines of different types. This meant reorganizing the work of hundreds of skilled employees and of dozens of managers as well. And they were able to do this without interrupting production or jeopardizing quality.

I was dumbstruck by this achievement, especially compared with the halting efforts I was observing at General Motors and other companies to create even one model line, much less a whole model facility. Dan and I decided to include this and several other kaikaku examples from Pratt in Chapter 8 of our book in hopes of inspiring other companies to be more aggressive in their lean efforts.

Once the examples for the book were written up and Lean Thinking was published in 1996, I continued to visit Pratt simply to see how the lean transformation was proceeding. And in 1997 Pratt's parent company, United Technologies, became one of the five founding sponsors of LEI. For some years this arrangement gave me open access to UTC where I was a sort of nagging conscience who showed up from time to time to see if they were keeping the faith.

What I saw over time was not what I had hoped. The kaikaku efforts were impossible to sustain due to a lack of basic stability and management focus. So Pratt – and UTC more broadly with their ACE program – continued to pursue lean but through kaizen, not kaikaku, and usually with point kaizen rather than system kaizen involving whole value streams or model lines. Process improvement shifted from a big bang to tiny increments. And this has been true in the entire lean movement. Indeed, I hardly ever hear the term kaikaku today and get puzzled looks when I use it.

Recently, I heard the magic word again when I was contacted (Bob in the "Constancy of Purpose" essay in Gemba Walks) to ask if I would like to observe an example of old-fashioned kaikaku as it was happening at Esterline, a first-tier aerospace supplier in Everett, Washington, near Boeing, one of its largest customer.

Long-distance learning is surely one useful purpose for airplanes, so I was soon on my way to Esterline to observe the middle of a five-day kaikaku as an entire facility with 700 employees was transformed. When I arrived every machine and every piece of office equipment had been moved out of a 216,000 square foot facility, to a tent city in what had been the parking lot until the weekend before. Hundreds of skilled trades were busy with scissors lifts relocating all of the ceiling-mounted utilities for the new locations of equipment in an otherwise empty building. (My sole contribution, it should be clear, was to give a little pep talk to the transformation team, putting the idea of kaikaku into historical perspective going all the way back to transformation efforts at Toyota in the 1950s.)

The kaikaku plan was to create four start-to-finish, mixed-model, high-volume production lines (takt times ranging from 2-14 minutes) in place of the process village layout, to introduce a new pull-based, "line back" takted material supply system all the way from the supply base to every station working to takt time to the Customer, and to introduce a new management system where the key management position was the value stream leader rather than area (process village) managers. (That is, the physical flow of production, the information and materials management system, and the operating/management system were being transformed simultaneously.) Now the factory can flow.

I couldn't stay for the end but Esterline has supplied me with the details of what happened, which can be summarized briefly as follows:

- Two new product lines were added with no additional labor or space.

- An additional 20,000 sft of greenfield was generated.

- Labor productivity was increased 30%.

- DTM (Days to Manufacture) was reduced over 50%.

- Esterline management's perception at every level of the amount of improvement possible within a relatively brief period was radically transformed.

- Recognition the transformation has just started...

Wow. There must be some fine print. Indeed there is. As the event leaders noted when I arrived at Esterline, the kaikaku event required several months of preparation (by means of catchball and attention to weaknesses in existing production methods and management mindsets using a robust risk mitigation process). And it was being led by a new team of Esterline CI Leaders trained at Rohr Corp. and at Goodrich Aerospace over the last 20 years. And, the big "and", it had taken 14 years at Rohr and then Goodrich to figure out how to do sustainable kaikaku (at over 16 factory-wide kaikakus in total)!

First they had to understand how to master and sustain 5S, takt time, standardized work, line balancing, proper materials presentation, level scheduling, real-time problem resolution through daily management, policy deployment, and kaizen. Only then were they finally ready for kaikaku. And it was the key to rapidly spreading what they had learned, at Rohr and in one business unit of Goodrich after it acquired Rohr, to all of Goodrich. And now ex-Rohr/Goodrich managers who had recently left for Esterline are transforming Esterline at a pace previously unimaginable.

So what is the take away for lean practitioners? My thought is that lean transformation will always need to begin with evolution: kaizen and model lines, pull materials supply, level scheduling, real-time problem resolution, and policy deployment. These create the basic stability and lean management mindsets needed for sustainable improvement. (So their purpose is actually to train an entire management team in a new way of thinking, not just – or even primarily – to address specific business problems.)

But once an organization gains experience with these tools and managers learn to think in a new way there is an opportunity for truly dramatic and rapid transformation in every facility and department by means of experienced line managers applying all of the tools and management methods in unison. Currently the organizations I see, and I visit many every year, are completely squandering this opportunity.

So, should you pursue evolution or revolution? I used to be a lean revolutionary. Then I became a sober evolutionary as the limits of revolution without stability and prepared managers became apparent. Now I'm an evolutionary/revolutionary believing that we really do need to go slow to go fast but that once we have gone slow to learn we then really do need to go fast. (Think high-speed yokoten from an inflection point.) Perhaps you should be an evolutionary/revolutionary too?

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – The pandemic has brought back into the spotlight the common misconception that Just-in-Time causes disruption when spikes in demand occur. Torbjørn Netland debunks the myth.

FEATURE – Digital organizations are starting to recognize that Toyota’s unique approach can show them the way forward, just like it does “traditional” organizations. Here, we hear from a few startup CEOs following their trip to Japan.

FEATURE – Following the recent CXO Summit in Singapore, a team from the Lean Global Network reflects on the partnership with SIT and its potential effects on the city-state.

CASE STUDY – Clinical trials are known for their rigorous analysis and approval process. The experience of Roche Brasil teaches us what lean and agile thinking can do to speed it up.