Jim Womack on the lean shut-down of Toyota Australia

WOMACK'S YOKOTEN – On October 3, Toyota will cease its manufacturing operations in Australia, but the way it is managing the transition - in the leanest way possible - holds great lessons for us all.

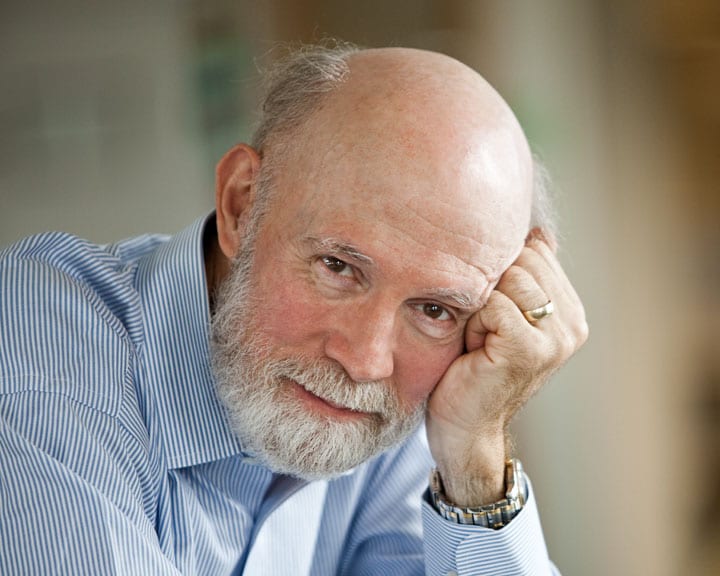

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

We all love a start-up. A world of opportunities where no mistakes have been made and no legacy assets hold us back. And in the Lean Community we love a lean start-up even more, with enhanced prospects for getting the product right and a chance to avoid introducing muda in any value-creating process. But what happens when even the leanest organization finds itself located in the wrong place with an impossible mission and needs to shut down? What are its obligations to its people? How should it proceed?

I've had occasion to think about this since visiting Toyota's Altona facility in Australia two weeks ago, when I was there for Lean Enterprise Australia's 2017 Lean Summit. Toyota will close the manufacturing portion of the Altona site on October 3 after fifty-four years of assembling cars in Australia and thirty-nine years of manufacturing engines. So it was clear that my gemba visit during my time down under (and I always insist on a gemba visit when I go anywhere) must be to Toyota in Altona (a suburb of Melbourne.) Here's what I saw and learned.

Toyota came to Australia as a manufacturer in 1963 as it prepared to grow dramatically across the globe with the Corolla launch in 1966. Australia at that time had high tariffs, import quotas, and local content requirements on imported vehicles in order to create an import-substitution auto industry in a country with a small population. The only way to sell vehicles in significant volume was to start manufacturing. (General Motors and Ford had started much earlier along with Chrysler, which was acquired by Mitsubishi in 1980, before leaving in 2008.) Australia was a growing market and Toyota decided, under the government's rules, to manufacture small cars there. This was a type of product the other carmakers already in the country had not been paying much attention to, offering instead the larger vehicles with V8s and rear-wheel drive that Australians traditionally loved.

The company was a financial success and, over time, as Toyota converted its local contract-manufacturing partner to a wholly-owned subsidiary, the Toyota Production System was steadily introduced. This was not easy due to the traditional union environment in Australia, with rigid work rules and grievances for even the tiniest technical violation of contract terms (making kaizen a tall order.) Even when I last visited Altona in 2003 TPS was still far from fully grounded in daily practice and the facility ranked at the bottom of Toyota's global operations in terms of productivity and quality. At one point I watched in amazement as a production associate refusing to wear the required protective gear scratched the paint on a car in final assembly while reaching to install a part.

But Toyota, in its Toyota-like way, kept working on these problems and in recent years Altona improved dramatically to become a top performer in the Toyota global manufacturing system in terms of quality and productivity. (Cost was another matter as I will explain in a moment.) And it did this by making an enormous and continuing investment in up-skilling its people to make every employee into a problem solver. (89% of team members have participated in Quality Circles in the past year – even as the plant was preparing to shut down – and 100% of the projects were completed.) Indeed, the Altona plant I saw two weeks ago was a brilliant example of lean practice and on the day it ceases production it will be one of the best production facilities in the world.

So this is truly a case of a "lean" shut-down. How can it be necessary?

The back story is that as auto production grew in Australia the price of sustaining it (a price measured in the high selling prices for cars produced locally and the cost of government financial supports for exporting) grew steadily as well. By the 1980s, politicians were beginning to conclude that either the domestic industry must improve its productivity and lower its costs dramatically or the restrictions on imports needed to be relaxed or eliminated. In the spring of 1987, Bill Scales, the chairman of the new Automotive Industry Authority of Australia formed by the government to address the problem, called me at MIT to ask how the local industry could be transformed and saved. His organization joined the International Motor Vehicle Program at MIT and we talked about this challenge for many years.

Then something else happened: the global boom in commodities prices, fueled by the growth of China as a manufacturing country. Australia had a handful of aces in commodities – massive iron ore deposits, massive copper deposits, massive bauxite deposits, all in unpopulated areas where extraction was easy. Rather than selling companies or land to China, Australia literally sold the country, to be ground up and loaded in ultra-large ore carriers for export. The consequence was a very strong Australian dollar over many decades, making manufactured exports expensive and imports cheap. At the same time, Australia took a conservative stance toward immigration with the result that it may always be a country with a massive land area but a small population (currently 24 million) and a domestic market that is small by world standards: 1.2 million cars sold in 2016 versus 25 million in China and 90 million in the world.

Toyota did its best to deal with this situation by turning itself into an exporter of 70% of its output, almost all to the Middle East, where Toyota has long had a very strong market presence. But on a cost basis it never worked: the need to produce relatively small volumes (150,000 vehicles and 150,000 engines per year) in a high-wage country (due to the strong currency) with many imported parts from distant locations to make products for a major market on the far side of the world –even as succeeding governments continually relaxed barriers for automotive imports and local selling prices fell – meant that at best Australia was marginal financially as a manufacturing site.

Then General Motors and Ford announced in 2013 that they would leave Australia as manufacturers, pulling down the local supply base they shared with Toyota, and the national leadership of Toyota's union inexplicably decided to hold out for better benefits in a collapsing industry and went on strike in 2013. Bad things do happen even to lean companies and Toyota's conclusion at headquarters was that the long-term situation was hopeless. Automotive is a tough, global business and top-level management has to think about the greatest good for the greatest number of its people over the long term.

So what has Toyota done to make the best of a bad situation? And what does this mean for the rest of us?

First, they told the truth and the CEO did the telling: Akio Toyoda flew the 11 hours from Toyota City to Altona in February of 2014 to announce Toyota's decision to stop production in front of the entire work force before anyone else knew. (Note that the CEOs of GM and Ford were nowhere to be seen when bad news had to be shared about their Australian operations. They sent regional managers instead after word started to leak out.)

Second, the closing date was set three and half years in the future, in the fall of 2017, to allow time to transition the workforce to new careers or into retirement with a severance package. (The average worker will receive about two years' pay at the closing.)

Third, Toyota accepted the fact that closure of the plant required a transition to new work for most employees and that Toyota needed to take the lead. Senior management understood that its obligation before producing the last car was to manufacture 2,600 upskilled and reskilled employees equipped for new careers.

Some of these new careers (about 140) are within Toyota's sales and service organization where I saw a truly lean warehouse for service parts being created by employees transferring from the manufacturing organization. Other manufacturing employees with improvement skills will soon be working with the local dealers to improve their processes. And more work is being created within Toyota for the benefit of Australia by means of a new TSSC organization parallel to the one in the United States. It will be sharing Toyota methods with organizations in Australia wishing to learn, with a special emphasis on helping non-profit and charitable organizations make more effective use of their resources. (Lean Enterprise Australia hopes to form a strong relationship with this group.)

But it was clear that much of the workforce would need to find new jobs outside of Toyota and mostly outside of manufacturing. (Remember that Australia is not just a difficult venue for making cars. It is stony soil for any manufacturer without a protected niche.) And most of the workforce had only worked within manufacturing within one company.

Toyota's response was to focus on continuous improvement of its people through reskilling and upskilling. Reskilling has meant developing career plans for each employee with the support of trained case managers and finding the appropriate training. By the time of the closure, 1,200 employees will have gone through reskilling to find jobs as nurses (26), pilots, lawyers, commercial drivers, chefs, construction workers, small business operators and, in at least one case, as a high school science teacher. (This was the current environmental manager who helped me find a hydrogen fuel-cell Toyota Mirai to test drive in the US, of which more next month.)

Upskilling, by contrast, has meant getting 600 employees who already had a government certified job grade (e.g., a shop floor team member has a Certificate 2; a team leader has a Certificate 3; a group leader has a Certificate 4) re-certified at one higher level as they search for a new job. Importantly, because most employees have only worked at Toyota and are simply unaware how superior its practices are to typical Australian companies, it has been important to make them aware of how much they know and how this makes them marketable.

In combination with the large number of high seniority employees who are ready for retirement (with 3.5 years of notice and two years of wages at closure), these steps mean that practically every employee is ready to transition to a new career or a new stage in life.

A final feature of Toyota's plan, which I found truly remarkable, has been to continue improvement activities at Altona at the traditional pace until the last day with the objective of making "the last car produced the best Toyota produced in the world" for a place of honor in the Toyota Museum. The idea is for employees to keep honing their skills until the last moment and to make the world aware of the high level of engagement by everyone at Altona even in difficult circumstances, an intensity they can share with their future employers. (I've long made jokes about improvement activities at hopeless companies as "kaizen on the Titanic" but at Toyota Altona I had to change my view. They have been continuously improving the life boats.)

So what's the take away for the Lean Community? None of us is likely to need help with the shut down or transition of a truly lean organization like Altona. But most of us will encounter situations where a far-from-lean facility or company is simply in the wrong business or in the wrong place no matter how lean it might become. What should we do? My answer is simple: urge these organizations to emulate the high standard Toyota has now set for the world at Altona.

Have the CEO tell the truth. Start planning in time for a complete transition of the workforce. Develop a plan for every employee for upskilling and reskilling to find equivalent or better alternative work. Continually improve operations to the last minute to demonstrate employee ability to cope with adversity.

If we can do these simple (but hard) things we can help turn the world's shut downs of facilities or firms into successful transitions (indeed, personal start-ups) for their employees, as I believe Toyota will achieve for its people in Australia by October 3.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – In this interview, Michael Ballé discusses lean thinking as a strategy, how to unearth problems, and the best (or only) way to initiate a lean transformation.

CASE STUDY – With plans to double capacity year on year in its new precision machining business, a Turkish company found in lean a way to control growth by stabilizing old processes while new ones are introduced.

INTERVIEW – Planet Lean speaks with David Mann about the importance of combining the lean production and the lean management systems – the tools and the culture – to create sustainable results.