Jim Womack discusses Uber and Airbnb

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – The sharing economy came with a very “lean” promise – underutilized resources made available to those who need them for a reasonable fee – but not all that glitters is gold.

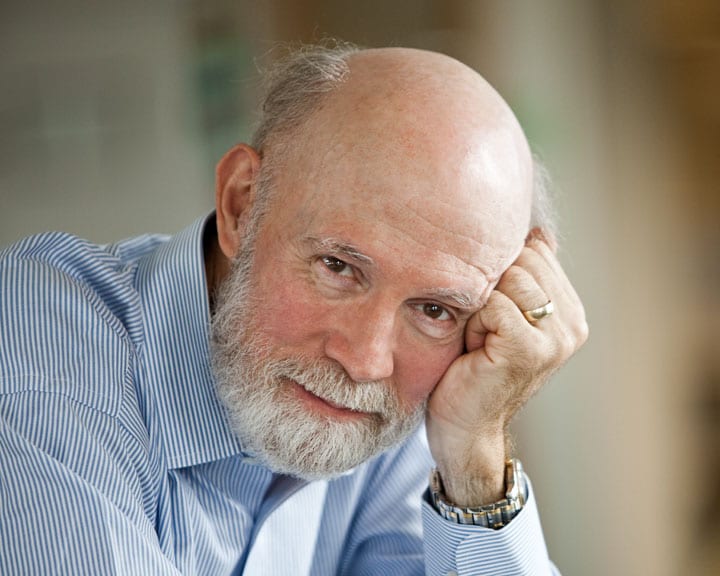

Words: Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor, Lean Enterprise Institute

I got my first car 40 years ago – a hand-me-down from my parents. My first, joyous thought was, “It’s mine; always there and available when I need it.” I never considered lending it to anyone, even my best friend, and would have blanched at the thought of carrying strangers to make a bit of money if this idea had even occurred to me. My vision of adult life was that as my income grew I would obtain more and more personal assets for my exclusive use. No more crowded buses! No more roommates!

Once I got to Boston to go to school (driving alone in my hand-me-down car) I laughed at the counter-culture T-shirt I saw in Harvard Square, “The person who has the most stuff when he dies wins.” But it was pretty much what I believed. And most people in most countries, rich and poor, seemed to feel the same way: Poor people didn’t have many assets to share but found it in their interest to share when they could. Rich people had lots of assets but didn’t need to share and didn’t want to.

Here’s a simple evidence: Vehicles in poor countries, then and now, were/are packed with people and cargo – relatives, friends, fellow villagers, and chickens, plus strangers willing to pay or barter a small amount (e.g., a chicken) for a ride. By contrast, vehicles in rich countries have averaged perhaps 1.3 occupants (with the number falling over time) and were almost never used as a form of exchange. In addition, these vehicles were/are hardly used at all, averaging only about two hours of utilization for transportation in a 24-hour day.

In recent years things have changed: The world economy – now including China – has slowed down and shows no signs of regaining high growth. This leaves many people owning more assets than they can afford or unable to obtain the assets they need and with little expectation that things will change. At the same time the information cost of finding others wanting to share assets has plummeted because of the web. Suddenly we have the “sharing economy” involving many people who would never have considered the option before.

Said another way, for many people, some with a lot of assets and some with few assets, the definition of value has changed. A small loss of the value in one’s assets (because they are shared and sometimes not available) seems worth the gain in income while the extra trouble of finding someone wanting to share their assets, rather than obtaining your own, seems worth the trouble.

I think a lot about how the definition of value changes over time, but this doesn’t affect my definition of lean, which doesn’t change at all: Creating more value (however defined by the consumer of the value) with fewer resources. So I have been paying a lot of attention in recent years to the growth of the “sharing economy,” where consumers use the connectivity of the web to share the use of personal assets. I’ve found myself asking the simple question, “Is sharing lean?”

My answer is that it all depends. Let’s take an example currently at the forefront of the shared economy: Uber. As originally presented, the concept was for individuals with underutilized vehicles to “share” them with others needing transportation, as matched by the website. The presumption was that vehicles enrolled in Uber would provide more miles of transportation every day (compared with the 8.3% utilization of cars in advanced economies) while creating more value (income) for owners and more value (cheaper travel) for riders. More value from the same assets (resources) certainly sounds lean. (Full disclosure: I got the app and have been a heavy user, avoiding the need for a second, poorly utilized car.)

But in practice I find that Uber drivers today (and my experience is limited to US cities) are full-time drivers rather than people with other sources of income using their personal vehicles a few hours a day to make a bit of extra money. And a number seem to have obtained vehicles for this purpose (often by leasing) rather than using vehicles they already owned. In addition, the utilization rate of these vehicles may be falling as more and more drivers sign up for Uber, to the great benefit of Uber because it decreases the average wait time for passengers but to the detriment of drivers whose average income per hour falls proportionally.

At the same time traditional taxi services, which in concept are actually the same thing without the sophisticated matching technology, are being displaced, as witnessed by the plummeting prices of taxi medallions in big cities. This situation doesn’t mean that there is anything wrong with Uber or anything right with taxis (an industry that fell asleep years ago as limits on taxi medallions baked in monopoly profits and took away the incentive to innovate.) It does mean that determining whether Uber is “leaner” than taxi systems or the use of private cars for travel, as defined by creating more value with the same or fewer resources, takes a lot of analysis and has no easy answer.

The same thing can be said for Uber’s analogue in accommodations: Airbnb. The idea of taking one’s home (typically a household’s largest shareable asset, followed by its motor vehicles) and sharing it with strangers located through the web certainly sounds like more value being created from the same assets. (Remember that the gain in value by the user who gets a room at a lower prices is somewhat offset by the loss in value by the owner of the asset who no longer has flexibility to use the room whenever needed. But the sum is surely positive or no one would enroll their home in Airbnb and no one would try to find a room using the website.) But now one hears of properties being bought or built by owners wanting a low-cost way to enter the hotel business. The end result could be that the gain in utilization of Airbnb properties is offset by the loss of utilization of traditional hotels.

There is an additional feature of the sharing economy that is problematic for many participants. Network economics – where the most successful matching site eventually ends up with practically all of the traffic (think Google) – means that much of the gain in value from a financial perspective may wind up in the hands of the owners of the dominant network rather than with those sharing the assets. So, even when there is a substantial gain in total value created from widespread sharing of assets, it may not wind up with the asset owners. (Hence the current struggles in courts and with regulators over who gets the money from Uber and Airbnb.)

Lean thinking doesn’t have an answer to this last issue, any more than it can answer the question of who should claim the gains when a factory doubles its productivity through the application of lean management and methods or a hospital learns to treat more patients and treat them more effectively by applying lean principles. What lean thinkers can do is to raise the question of how lean any new innovation actually is and, ironically, to ask how lean the providers of these new services, such as Uber and Airbnb, are themselves. The dominant players seem certain to become vast bureaucracies subject to the same waste of resources as any other large organization. So we have work to do in the Lean Community even if these sharing economy concepts turn out to be less than lean in the end.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

BUILDING BRIDGES – In another article for their series, lean digital company Theodo tells us about their efforts to measure and reduce its lead-time to deliver product features.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – Somehow surprisingly, management schools teach very little about management, and when they do all learning is classroom-based. Instead, they should go to the gemba.

INTERVIEW – A team from LGN just spent a week on the gemba with Toyota veteran Hideshi Yokoi for a jishuken exercise. We asked him to explain to us how he used this practice while at Toyota Motor Kyushu.

FEATURE – This time of crisis is a perfect opportunity to use Lean Thinking to review processes, improve standards and prepare ourselves for the “reconstruction”, says Sharon Visser.