Why kaizen lies at the heart of lean thinking

INTERVIEW - What lies at the core of kaizen activity? How has the concept of kaizen evolved over time? Planet Lean’s editor Roberto Priolo discusses these and other topics with kaizen expert Mark Hamel.

Interviewee: Mark Hamel

Roberto Priolo: You have worked with lean for over 20 years now – how have you seen people’s approach to kaizen, which is your area of expertise, change?

Mark Hamel: Certainly in the US brownfields in the mid-1980s, with the help of the Shingijutsu consultants, the popular kaizen deployment approach was the kaizen event. Much of the incredible improvement within organizations such as Danaher, Wiremold, and Pratt & Whitney were driven by events. External and even internal coaches employed a “shock and awe” style in which they used sometimes deprecating language and bold actions (like driving a forklift through a wall to facilitate product flow), in addition to the cognitive, reflective and experiential teaching, to make big improvements and shake the batch and queue sensibilities of the managers.

While there was and is much more behind a true lean transformation, many companies grasped only the superficial. They tried unsuccessfully to replicate what they thought was a kaizen event driven implementation. With the publication of Learning to See and the popularization of value stream mapping, kaizen events (and projects and “just-do-its”) became more system driven. This really enhanced kaizen effectiveness and drove significant operational results. But still this approach, on its own, is not transformational in nature. This is certainly true from a mindset, employee engagement, and lean leadership behavior perspective.

In my opinion, this is often because we have forgotten, or perhaps never really have known, why we “do” kaizen. The purpose is indeed improvement, but the meaning is people. This encompassed the “what” and the “why” of kaizen.

Fortunately, more and more organizations are now embracing what some call principle-driven kaizen - leveraging the power of system-driven kaizen along with the transformational stuff of daily kaizen, where everyone helps improve the work, every day. This is largely enabled by the creation of a healthy and vibrant kaizen ecosystem that includes lean management systems and lean leadership behaviors. In summary, we’re getting closer to kaizen true north.

RP: At LEI Polska’s recent summit in Wroclaw, you mentioned George Koenigsaecker’s suggestion that 3% of the people in an organization should be devoted full-time to lean. Why is that the right percentage and what implications does moving away from it have?

MH: George Koenigsaecker’s figure represents his recommended full-time staffing for an organization’s kaizen promotion office (the lean function). He’s a bit more aggressive than the unofficial standard of 1 to 2% of total headcount. Whether it’s 1, 2, or 3%, the notion is that an organization that is truly serious about undertaking and sustaining a lean transformation needs to provide a requisite amount of dedicated resources.

The lean function typically develops and delivers much of the lean curriculum, facilitates kaizen activities (value stream mapping, kaizen events, quality circles, etc), coaches leadership, etc. Because a lean implementation will free up much more than 1 to 3% of the organization, this should be self-funding.

The lean function organizational structure should be flat, reporting to credible lean leaders, rather than a new sort of corporate bureaucracy. Now, it is absolutely critical to understand that the KPO does not abdicate leadership of the responsibility to ultimately be the primary lean coaches within the organization.

The reality that lean leaders are not fixers, but rather teachers is, unfortunately, very foreign to many people. Clearly, that requires a huge mindset change, a robust management system, new behaviors and capabilities, and often some changes in organizational design (for example, team leaders with a 25 person span of control have little time to facilitate problems solving).

RP: At that summit you also shared a study on a Toyota plant, which revealed how only 10% of kaizens are actually voluntary. This can be confusing at first… shouldn’t we try to get as much voluntary kaizen as we can?

MH: Actually, the study revealed that 10% of the measurable impact was generated through the voluntary kaizen of workers. The balance, or 90%, was driven by organized kaizen that was led by team leaders, production supervisors, and engineers. I must admit, when I first read through the study, I was a bit shocked. This “imbalance,” if considered, for example, within many US facilities may not be nearly so large, because many of the improvements would probably be categorized as voluntary in nature.

Interestingly enough, I have just come upon a book written by Robinson and Schroeder, The Idea-Driven Organization, in which they say that bottom-up ideas account for approximately 80% of the impact! Intuitively, this makes more sense to me for a mature lean organization.

But whatever the “answer” is we should try to get as much voluntary kaizen as we can, because it facilitates worker engagement, adherence to and improvement of standardized work, ownership, kaizen mind and problem solving capability, development for promotion, and improvements to safety, quality, delivery, and cost. Heck, according to an Employment Involvement Association statistic, the average US worker comes up with one suggestion every seven years, and less than a third of those are actually implemented. Compare that with some Autoliv plants that have in excess of 80 implemented improvement ideas per person, per year. I know that I don’t want to work at the “average” company.

RP: How much of our kaizens should be organized at the top as opposed to move from the bottom up, then?

MH: I think the mix of organized versus voluntary kaizen is situational, and depends on the organization’s level of lean maturity and existential concerns. For example, imagine you are launching lean in a sorely struggling brownfield using daily kaizen - suggestions, quality circle activities, mini-kaizen events, etc. – I wouldn’t think the rate of improvement around people, quality, delivery and cost would be particularly dramatic in the short term If you have a patient on the operating table, your treatment would not be limited to providing large dosages of vitamins.

In the typical lean launch, as reflected in Lean Thinking, value stream mapping comes first, followed by the requisite kaikaku-type activities. Of course, that should be done in parallel with a lean management system implementation to ensure the sustainability of results and to facilitate cultural transformation.

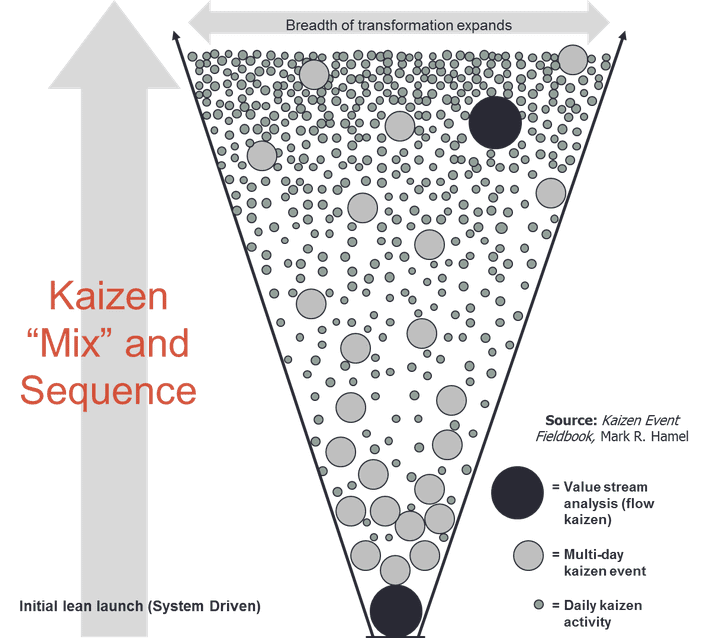

The top down/bottom up kaizen mix can be portrayed by the “champagne glass” example (pictured below). As you can see, in a traditional lean launch, the kaizen activity starts with value stream mapping, which then pulls kaizen events (as well as projects and just-do-its). Smaller, daily kaizen activities then become the predominant form of kaizen.

RP: What lies at the heart of kaizen activity?

MH: A respectful and humble environment, I would say. One in which Toyota’s 3 Cs - challenge, creativity and courage - are well applied. I want to challenge you to achieve the target, empower and encourage you to use your creativity, and provide a blame-free environment to give you enough courage to experiment, make mistakes, and learn. That’s what real PDCA, with the proper scientific rigor, is about.

RP: You mentioned suggestions earlier. As a manager, how do you turn down suggestions without stifling creativity?

MH: Again, we must do everything with humility and respect. The purpose of every kaizen, in my mind, other than obviously trying to make something easier, better, faster, and cheaper, is individual and organizational learning. So, turning down a suggestion must be done with care and should be an opportunity for teaching. The first question around any suggestion is, “What problem are you trying to solve?” This gets at the rigor of the problem statement, essentially the identification and articulation of the gap between what should be happening versus what is actually happening.

Often, folks don’t quite get this right, thus providing a great opportunity for coaching. From there, we can get into an understanding of the root cause and the sufficiency of the countermeasure. As we might guess, not all “suggestions” survive this process. For example, some suggestions are not real suggestions, but rather problems of awareness.

What is important is that the leader coaches the submitter of the suggestion so that they reflect, learn, and own the suggestion. And, it’s not just the leader who may “turn down” a suggestion. The submitter’s peers may respectfully share their insights. If the suggester is intellectually honest, they will typically understand why their suggestion may not survive, at least in its current state, and that it may require more work.

Others suggestions might be rejected or deferred because they can’t pass another critical question, “Why are we trying to solve this problem now?” This is where the team member, by virtue of the team’s visual process performance metrics, an internalization of the organization’s true north, should already have a very good idea relative to where their suggestion might fall relative to priority.

Often prioritization is a team-based discussion during the daily team huddle/reflection meeting and is centered around impact and effort. So, ultimately, it becomes less of a thumbs up/thumbs down verdict for each suggestion, but more of a dialogue, a partnership, and a growth opportunity within the context of the lean management system.

THE INTERVIEWEE

Read more

COLUMN - As the lean community grows, experimenting with tools for self-organization like Open Space in order to build stronger lean networks.

INTERVIEW – The authors of the new book The Power of Process debunk some of the most common myths about lean process development.

RESEARCH - Standard work is not meant for senior leadership, but there are activities that CEOs can carry out systematically to support a lean management system, starting from problem solving.

COLUMN - Menlo Innovations may not define itself as a "lean organization" but there is no doubt that its management style is akin to the principles lean teaches. Here, a front-line Menlonian shares her thoughts on the company's culture.