Grievances first

NOTES FROM THE GEMBA – How do you kick off a lean journey? This French company has chosen to begin by analyzing and tackling each customer complaint.

Words: Catherine Chabiron, lean author and member of Institut Lean France

When Alain Genet created Acta Mobilier 30 years ago (mobilier as in moveable furniture), he already knew that he would not want the business to grow at the expense of his employees. As I learn from him this morning, in his office, the name of the holding of which Acta Mobilier is part is Valeurs (“Values” in English). And values, such as trust and respect, are a key expectation in the group.

Alain has clear economic ambitions and knows that growth implies fully satisfying customers (“If our customer wins, so do we,” he tells me). All the more in Acta Mobilier’s line of business: they build stands for temporary exhibitions and luxury brands, such as Chanel or Guerlain, work on the layout of 5-star hotels or arrange the windows of French department stores. Not to mention the elaborate kitchen facades they help design and build for most French and German kitchen makers (the cost of the kitchens they contribute to range from €50k to €300k).

Alain knows one thing for sure: that in a business characterized by ever higher levels of specificity and quality expectations, to completely satisfy customers means to achieve the daily commitment of each individual to doing the best job possible. Another firm belief of his is that everything should be done to develop individual and collective capabilities, within Acta Mobilier, but also through relevant and strong partnerships helping employees to learn, grow, experience new techniques, and better manage processes.

It is no wonder, therefore, that two years ago Alain saw in Lean Thinking a perfect match for his company.

HOW DO YOU START WITH LEAN?

The goal of my visit to Acta Mobilier today is to try and answer one of the most difficult questions we have in the Lean Community: how do you start? After discussing a bit of background with Alain and Alexia Malexieux, the Industrial manager of Acta Mobilier, we decide to try and get a better understanding of the activities taking place on the shop floor. While we walk the gemba, Alexia explains how the company has progressively developed new industrial processes. In the kitchen line of business, for example, they were initially mostly proposing a façade finish with gloss lacquer, they then expanded to waxed concrete (a real commercial success) and lately developed a metallic finish. While the basic material in their activity remains MDF (Medium Density Fiber) boards, the different industrial processes forced them to install production workstations here and there to cut, process, sand, blend colors, paint or apply waxed concrete, polish, pack and ship. I feel a bit lost in this process village: the flow does not make sense to a newcomer and it seems that there is a risk that work-in-progress might be dispatched to the wrong production line or stored in a corner where no one will remember it.

“We actually thought we would start our lean transformation with flow,” Alexia confirms, “but discussions with our Sensei led us to move in an unexpected direction. We first needed to protect the customer.”

START WITH THE CUSTOMER

Even though Acta does not have that many customers (they operate in the B2B world), their expectations are incredibly high: poor quality in a premium kitchen or a late delivery for an exhibition are just not acceptable. “We had about 40 complaints per week, and we were relying on our quality expert to answer them, but she was a bit overwhelmed and short of excuses,” says Alexia, looking back at the time when lean was not in the picture yet.

The first step in Acta’s lean journey, therefore, was the implementation of a large board in the main corridor, entirely dedicated to customer complaints. The board is visible to all, including customers if they happen to visit. Recurrent complaints are sent to the production area that created the issue and worked upon there. While containment measures, such as sending a replacement part to a customer, are immediately implemented, the objective of the paperboard analysis is to understand the root cause of the problem and identify the corrective actions that will prevent it from recurring.

In 2018, the effort was obviously paying off and Acta finished the year with an average of 20 complaints per week (half the number they started with in 2017).

Unfortunately, as we all know, lean is not a bed of roses. The customer complaint daily routines became business as usual, production operators were not always informed or involved as they should, customers were not systematically listened to on the relevance of the proposed solutions... and Acta slipped. The number of complaints started to grow again in September 2019.

“This was a shock,” says Alexia. “We relied on the tool to do the job for us. We forgot that we needed to put energy and commitment into it, and follow up.”

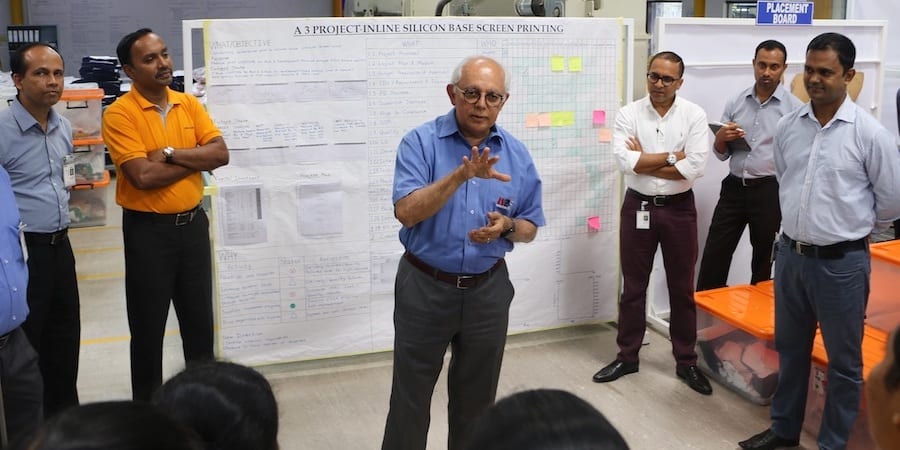

As our gemba walk continues, we reach the corridor where the complaints board hangs just as the daily meeting is starting. They just recently introduced a sheet for each complaint to ensure all key steps are addressed and dealt with promptly. The sheet includes the customer’s point of view (La parole du client), both on the problem and the solution, and the actions that Acta Mobilier is planning to take (containment, communication to shop floor, root-cause analysis and countermeasures).

Every day, the Production, Sales and Design teams meet to learn about new complaints and to follow up on the actions taken (by the way, so does the Executive Committee, once a week). Some complaints are considered “accidental” and taken off the board, so long as a solution has been found for the customer; others are kept on the board to work on their root causes. One example is just being discussed as we approach the team: the set-up of the machine is such that if a customer wants a special cutting effect on one single side of a kitchen door, the tool will ignore the spec and copy the same effect on all four sides. The set-up clearly needs to change.

As the meeting draws to an end, the group confirms that issues can be of all kinds: a mistake as the order is taken or entered in the system, a design issue, a production mishap, a problem with transportation, etc. “What we are trying to improve here is the time we spend with our colleagues to explain the constraints and issues we create for our customers and think out solutions together,” Alexia tells me.

LISTEN TO YOUR EMPLOYEES

Interestingly, aware of the fact that some issues can be traced back to the initial discussion with the customers and the poor understanding of their requirements and constraints, the Sales and Design teams have launched initiatives to improve the situation in both the Kitchens and Shops/Exhibitions Layouts areas.

Alexia, Alain and Raouf, in charge of Kitchen Sales, explain the dramatic change they have implemented: “We were forcing our own design vision onto the customer, half listening to their real needs, and with little thought given to how feasible it was to produce what we were proposing. What we do now, when we are expected to produce a specific request, is first to spell out the customer needs.” They show me a large board in the Kitchen Sales office, tracking current customer specific requests and the solutions the team needs to find if they are to meet those needs. There is a daily meeting between Sales and Design to try and answer two questions that, I believe, are key in any product development environment: what does the customer really need? And is there something we do not know today (a technique, a material, a competence) that we need to learn?

For each of the questions raised, the project leader will now go to production with similar parts, and walk the flow upstream from shipping to cutting, to ask operators and team leaders at each workstation the same three questions – what problems did you encounter today with these types of parts and what other problems do you foresee? What are your recommendations? What do you expect from your internal suppliers (upstream workstations) when it comes to this product?

Alexia comments: “Once we have understood what we can or cannot do, we build a prototype. This prototype will be followed step by step by the project leader, this time in the flow direction, from cutting to shipping.” The goal is to listen to operators as they build the prototype and note down any problems they encounter (and take action as needed). The prototype is then sent out to the customer: whether the sale is concluded or not, the team will debrief on the learning points.

Alain Genet is adamant: “We learn a lot from this process, discovering many details we previously weren’t aware of.” The idea of a regular discussion with operators actually started in the Shop/Exhibitions Layouts area, where the team holds a weekly meeting, every Wednesday, between Design and Production, to discuss design issues, production problems and installation constraints (installation is a key step in the Layout process).

I am told the story of large decorating panels for which a special casing was built for transportation. Because of the size of the panels, the packing team would systematically search for MDF scraps and build wedges to ensure the panel would be protected from any vibrations or movements during transportation. As this is a recurrent issue (those panels are needed worldwide for a French automaker), they had to build those wedges time and time again. Thanks to the weekly reviews, the relevant information has now been included in the cutting specs and the wedges are delivered to Packing together with the panels.

So, how do you start lean? There might be other ways, but can you ever go wrong when you sincerely start listening to both your customers and employees like Acta does?

JUST-IN-TIME TO GO FURTHER

Both Alain and Alexia are convinced this is not enough. Although Acta already offers a lead-time of two weeks in the Kitchen business (their competitors are stuck at around four weeks), they are conscious that their flow is far from optimized and that just-in-time techniques would really help them face up to some of their most pressing issues. And again, how do you start when your production area is a process village that developed wherever space could be found?

One of the first concepts they introduced was takt time. Each production cell is working at takt time, with production boards showing the actual production per hour versus the objective at takt. I am standing in front of one such board and see that the target for the cell is based on a takt time of 42 seconds (or 86 parts/hour): if the target Is not met, on an hourly basis, gaps are put on the board.

As we discuss takt time and the hourly analysis of problems, Alain and Alexia have another story for me, this time on the gloss lacquer polishing process. Once painted with the lacquer, the panel has to be sanded and polished to acquire the perfect evenness it needs. To achieve this, Acta bought and installed a sophisticated, fully automated machine, 14 meters long, able to process 20 parts at a time. They even designed carts that could carry the parts to and from the machine without touching or damaging each other. But they had a regular 40% non-conformity on the process. They were studying Paretos at length but could not figure out what the problem was. In the meantime, the lead-time exceeded 11 hours.

This is when they took a very bold step – after a lot of discussion, as most operators, team leaders and engineers feared it would not work: they disposed of the big, sophisticated machine, and launched one-piece flow on an old, much smaller, machine, as they believed this was the only way to understand and prevent defects. The operator was now able to see the thick areas where he had to insist on the sanding, and as a result the number of defects was cut in half. The lead-time went down from 11 hours to 10 minutes for any given part.

They started to track the takt time and the defect rate on this manual process, and the morning and afternoon shifts began to meet daily to discuss issues. Even though 20% of defects is still far too high, thanks to one-piece flow Acta is now able to see issues as they happen – not 11 hours later, once the batch is complete.

The carts designed for 20-part batches also ended up in the garbage bin. This was the cherry on the cake: they gained so much space with the disposal of the big machine that they could afford to bring forward the shipping area and to redesign it. The Truck Preparation Area (TPA) now shows the status of readiness of each upcoming shipment with simple, yet effective smiley faces. Again, the idea is to protect the customer and ensure the company is delivering everything as scheduled.

Alain and Alexia encourage all team members to attend lean classes and be active members in lean communities. They themselves spend hours reaching out to other practitioners and gathering information and a practical understanding of lean tools and principles. To further improve the lead-time, by insourcing the painting preparation process, the team was able to improve the lead-time twentyfold, which gave them an additional competitive advantage as they can deliver both standard and customized colors within the same lead-time (two days). They also cut the paint stocks by half in five years after switching from push to pull in that same paint preparation process.

As they continue to investigate each component of the Toyota Production System, Acta never loses sight of the need to keep customers happy. In this never-ending learning process, each small gain on quality or lead-time is a way to do a little better for their customers.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW – Prior to his talk at this year’s Lean Transformation Summit, the CEO of a large apparel manufacturer tells us about the company’s lean journey, and its impact on Sri Lankan society.

COLUMN - As the lean community grows, experimenting with tools for self-organization like Open Space in order to build stronger lean networks.

COLUMN – In the first of a new series, Boaz Tamir explains how understanding the knowledge and development capabilities of our team can provide the foundations for more dynamic and safer innovation.

WOMACK’S YOKOTEN – Last week, during a study mission in Japan, the Lean Global Network visited Toyota. Here, Jim shares his thoughts on what we saw and learned.