Lean healthcare: improving Emergency Departments in the UK

FEATURE – Introducing initial assessments by senior doctors and bedside diagnostics to improve the efficiency of the Emergency Department: a lean healthcare experiment in England.

Words: Dr Paul Jarvis, Consultant in Emergency Medicine, Calderdale & Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust and CEO, P&H Medical Consulting

My personal lean journey started when one of our senior nurses broke down in tears in my office.

Emergency Department (ED) nurses are a formidable breed: it is not uncommon for them to stay long after their shift has finished just to make sure their patients get the right care. In my experience, they don’t even mind being busy. In fact, they thrive on it. What breaks them, however, is when they are so overloaded they cannot deliver the quality of care they know their patients should receive. This is what happened to our senior nurse, who was so overburdened that she felt patients were suffering.

Perhaps it was my inner hero fighting to get out, but seeing her cry made me feel I had to rescue her. I saw it as my responsibility as one of the senior doctors in the department to fix our broken system. Throughout my professional life I had only ever experienced one way of working, which was so embedded in how I thought and behaved that when I tried to redesign our processes all I did was recreate what we already had. Somehow, I needed to be reprogrammed so that I could see beyond what we already had. I was going to need some help if I were to change our department.

I attended a course with Professor Daniel Jones’ team at the Lean Enterprise Academy here in the United Kingdom. They opened my eyes to the world of lean thinking and how it could be readily applied to healthcare. It’s no exaggeration that what I learnt changed my career.

When I returned to my hospital I decided I needed to hear the voice of the customer, so I invited a group of patients who had recently attended our Emergency Department to come and share their experiences of our service. We were a well performing organization when benchmarked against other hospitals in the United Kingdom, so I thought listening to the patient’s stories was going to be a positive experience. Unfortunately, I could not have been more wrong. Their stories made for very uncomfortable listening: they described poor communication from staff, long periods of waiting and being left unsure of what they were waiting for. It dawned on me that what they were describing were the symptoms of “push”: short bursts of value-adding activity sandwiched between long periods of inactivity.

Unlike most other industries, in healthcare the customer does not receive the product in its finished state, all neatly packaged, shiny and new. Instead, patients experience the product (the healthcare process) first hand, the good things and the bad (from what I was hearing from the patients it was mostly bad). They described things that as a doctor I was never going to experience despite having spent the majority of my working life at the gemba. Somehow I had become desensitized to what it must feel like to be a patient. Worryingly, by being immersed in a broken system for so long I had just learnt to accept it. Dangerously, I had started to believe that the patients had to accept it too - continually working in a broken system slowly erodes your ability to empathize.

Towards the end of the meeting an elderly gentleman looked me in the eye and said, “You know that stuff you do? Why don’t you do it at the start?”

Once I had got over the indignity of my medical practice being described as “stuff,” I realized I did not have an adequate answer to why we cared for patients in the order that we do; other than because that’s what we have always done.

This gentleman’s question became the basis for our new process at Calderdale & Huddersfield, which is known as EDIT – the Emergency Department Intervention Team. Now when a patient arrives they are assessed by a senior doctor and a senior nurse simultaneously and how the patient is investigated is determined by a standardized panel of investigations based on the symptoms the patient presents with. This is a far cry from our traditional way of working.

Historically, patients are assessed by a succession of doctors of increasing experience before they see the senior doctor who has the skill and experience to make a decision on the final nature of the care to be delivered. I can’t think of many other industries in which an inexperienced staff member is responsible for customer interaction and for designing how the product (in this case, the patient) should be treated. Yet this is vehemently defended in healthcare because of the false belief that having to treat patients with little clinical experience and large gaps in their knowledge is how doctors should learn.

In the new system, after the EDIT process and the investigations have been carried out the patient is assessed by a junior doctor who does the more in-depth, traditional clinical assessment. However, these days, unlike the previous way of working, they have all the results available to them to make a proper diagnosis. In addition, there is now a second senior clinician ensuring that the correct clinical decisions are made.

There’s more. We soon realized that our centralized laboratory was unable to run to takt. No matter how much we tried to optimize our lab’s performance we were unable to even get close to takt time. During our busiest times a new patient attends the Emergency Department every nine minutes, but the turnaround time for our laboratory is approximately one hour. We had to find a solution that resolved this mismatch to prevent a queue of patients waiting for blood results.

The solution we found is Point of Care Testing. Instead of sending blood samples to the hospital laboratory we now perform the test at the patients’ bedside using a hand-held blood analyzer. The cycle time for this device is three minutes, which is well within our takt target.

The impact of introducing EDIT with bedside diagnostics has truly surpassed our expectations. The time patients spend in the Emergency Department has been reduced by 42%. In addition, patient and staff satisfaction levels have greatly improved. Fewer people have to return to the Emergency Department in the week following their initial attendance and we are seeing better clinical outcomes for our patients.

Since making these breakthroughs I have started to help other hospitals internationally to implement a similar model of working. The next big challenge is to implement this way of working in a larger University Hospital that sees in excess of 100,000 patients a year (the one at Calderdale & Huddersfield treats 65,000). I will have the opportunity to do this in a large teaching hospital in London later this year.

This is just the beginning of our lean journey and the improvements that we have seen already are substantial, but I am sure there is so much more that we can improve both within the Emergency Department and in other parts of the hospital.

Potentially, we are all patients, so it is in everyone’s interests to make healthcare as efficient and productive as possible. We should all want to make it work.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

COLUMN – The author imagines an ideal, Jidoka-inspired response to the Coronavirus pandemic. This scenario might be utopian, but could it inform the definition of our True North?

FEATURE - In the second article in his series, the author provides helpful tips for those interesting in bringing some Lean Thinking to their parenting, focusing on the first five years of a child's life.

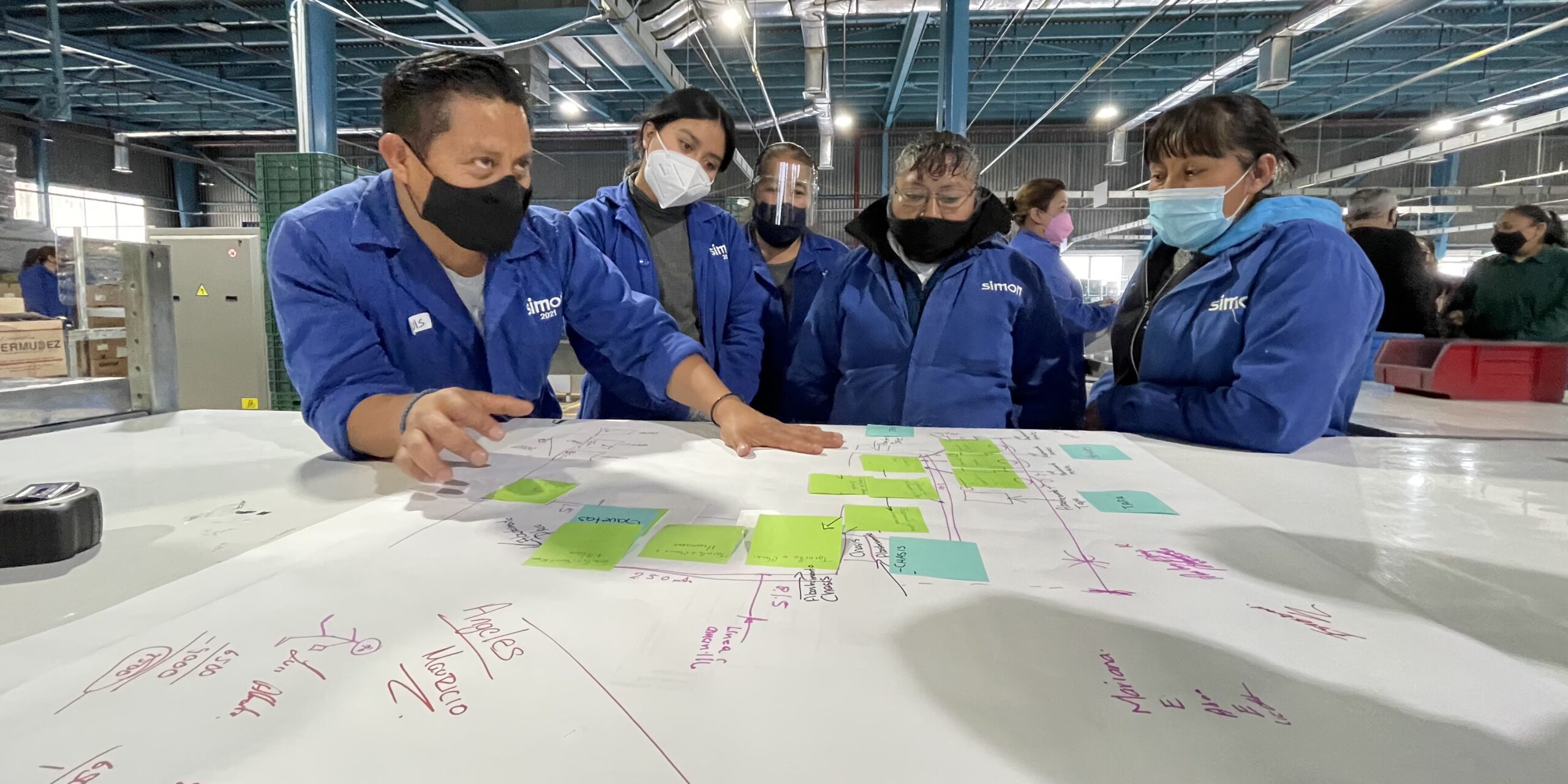

CASE STUDY – Starting in January this year, the Mexican plant of this manufacturer of lighting and electrical solutions has initiated a lean transformation that has already led to impressive results in terms of productivity.