“Global Jidoka” to mitigate the effects of the virus?

COLUMN – The author imagines an ideal, Jidoka-inspired response to the Coronavirus pandemic. This scenario might be utopian, but could it inform the definition of our True North?

Words: Roberto Ronzani, CEO, Istituto Lean Management – Italy

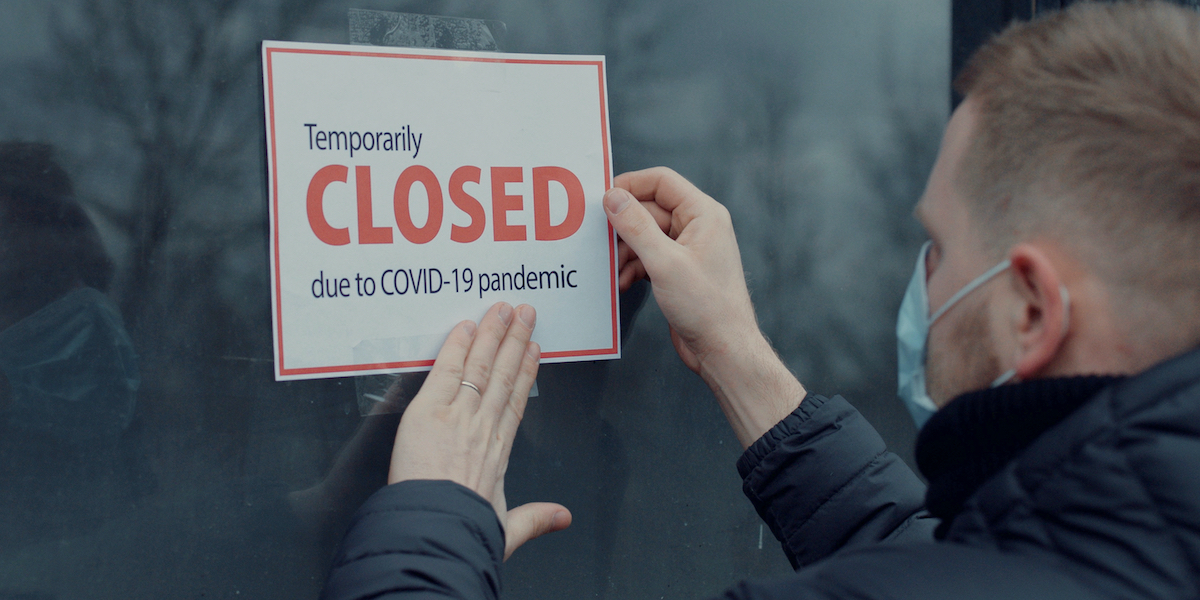

Lockdowns, drops in demand, the risk of losing customers: Covid-19 has paralyzed the global economy and there is no doubt the effects of the pandemic will be unprecedented and long-lasting. Nobody is immune and, like in a game of domino, any blow dealt to one sector will have serious repercussions on others.

At the moment, entire industries are generating little to no revenue – from tourism to hotels and restaurants, all the way to shops and consulting services. The money may have stopped rolling in, but it certainly hasn’t stopped rolling out: even though they are not working, organizations in these sectors are still paying rent, taxes, insurance and salaries, probably tapping into their reserves. Their very existence is now at risk.

Others, in the meantime, have continued to work and/or generate revenue, and their employees have continued to receive their salaries in full. It goes without saying, many of these activities play a vital role and allow our societies to continue to function under these extraordinary circumstances (I am talking about healthcare staff, farmers, pharmacists, supermarket clerks, etc). However, there is clearly an imbalance in our economy at the moment, with the money moving in one direction – from those who cannot work to those who can (be it because they belong to an essential sector or because they can can work remotely).

As I reflect on all this, I can’t help but think about the concept of Jidoka, invented by Sakichi Toyoda in the years between the 19th and the 20th century and subsequently developed at Toyota after the Second World War. What Jidoka teaches us is that, in the face of a problem, the whole process should be stopped to prevent defects from spreading to downstream activities and becoming harder and costlier to fix.

I have seen Jidoka in action a couple of years ago in Japan, while visiting Toyota supplier Tokai Rika together with my Lean Global Network colleagues. We were walking past a line where around 10 people were working, when an alarm went off at the last stage in the process. Immediately, the workers stopped what they were doing and stepped away from the line, waiting for the supervisor to intervene and take the process back to its normal working conditions. Only then did they go back to the line, picking up from where they had left off. Aside from a few minutes of stoppage – which also represent a cost for the business – there was no impact on production.

In our response to the Covid-19 pandemic, we have certainly applied Jidoka to protect our health: we spotted the problem, pulled the Andon cord and simply stopped everything. I now wonder whether a similar approach could be imagined for the global economy. Before the virus appeared, the “process” worked (albeit with its ups and downs and certainly unevenly across society), everyone had a role to play and received a salary for their contribution. Then the anomaly appeared, followed by the stoppage – which was by no means immediate – of only part of the process (the so-called non-essential activities). Another, smaller part continued to run.

So, what would a Jidoka approach look like in such a situation? In my mind, it would mean to pause all economic transactions. Nobody would spend any money for a limited amount of time – no rent, no taxes, no leasing payments, no bills, no salaries – except to buy food and medicines, the only real necessities (in March, demand has dropped for all products except for food).

Let me expand. Analyzing the food-related expenses of a number of individuals and families in the month of March, I have discovered that the cost of feeding one person is on average €9 per day. Let’s round it up to €10 (by the way, if all salaries disappeared, including those in the food sector, the cost of groceries would also decrease). Now, let’s take Italy as an example: with a population of 60 million, the cost of feeding everyone for a month would be 60 million x €10 x 30 days = €18 billion per month.

Think about it for a second. Assuming that at least 70% of the Italian population has access to at least €1,000 (in fact, according to research by Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, 78% of Italians could immediately access that amount for an emergency purchase), if people didn’t have to pay for anything but the food they need, it’s clear they could easily live through a three-month lockdown. The remaining 30% could receive help from the government, which would amount to just under €5.5 billion paid out of the national coffers – an amount that is much, much lower than what it’s currently planning to fork out. This way, the economy would be protected and, once it is safe to do so, it would be possible to restart without any further damage to people’s livelihood.

It would be a temporary freezing of the world economy (and certainly a sacrifice for us all), a “global Jidoka” that, implemented promptly and consistently, would also help to limit the spread of the Covid-19 virus. It would come at a cost, of course – all containment measures do – but this would be much more bearable than the gargantuan stimulus packages and anti-recession measures passed by governments thus far.

It this utopia? An ideal? Yes, it is! Turning it into a reality would require a set of shared values and approaches that our hyper-complex economic systems and societies don’t even consider:

- Teamwork, the idea that the individual wins only if the collectivity does – in this case, the global community.

- Respect for others, a concept we all preach but rarely practice (especially when our money is at stake). We are open to share with others, so long as there is enough for us.

- The ability to think outside the box, with an innovative spirit, and to make decisions based on facts and measurements rather than the “ideas” of the often-ill-advised leader du jour.

- Following an agreed-upon set of rules even in an emergency that are constantly reviewed and improved – what we lean thinkers call “standards” and “kaizen”.

This will always be a utopian scenario, but there is no reason it shouldn’t show us the way forward and act like our True North.

Now, back to reality, what are the lessons we can draw from this global ordeal and what are the actions we should take next? (Especially considering experts are warning us there might be more of these events in the future.)

First, we need to assess our response over the past couple of months and understand what didn’t work – both from a healthcare point of view (for instance, the spread of the virus in hospitals and retirement homes) and an economic point of view. Secondly, we must define new standards to contain the problem and protect our health and our economies as we strive to get closer and closer to our True North. Finally, we need to study, develop and experiment with solutions that immunize our “process” against “anomalies” such as Covid-19: a vaccine on one side and countermeasures in the organization of our societies and economy on the other.

I firmly believe that Lean Thinking can help us to define and carry out each and every one of these actions, to ensure we can provide the best possible response to this monumental challenge.

This article is also available in Italian.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Lean coaching is all the rage these days, but to what end? The author reframes the role of a sensei as an expert in achieving productivity by engaging everyone in kaizen.

INTERVIEW – A team from LGN just spent a week on the gemba with Toyota veteran Hideshi Yokoi for a jishuken exercise. We asked him to explain to us how he used this practice while at Toyota Motor Kyushu.

RESEARCH - Standard work is not meant for senior leadership, but there are activities that CEOs can carry out systematically to support a lean management system, starting from problem solving.

FEATURE - Two weeks ago, the authors shared their thoughts on mindset. In part 2, they discuss how to grasp the true spirit of lean.