Corporate world: how does lean work in large organizations?

RESEARCH - This interesting study, based on 44 Volvo plants and 200 Volvo interviewees, looks at how the implementation of lean thinking influences a plant’s performance over time.

Words: Torbjørn H. Netland, NTNU, Industrial Economics and Technology Management, Trondheim, Norway; Kasra Ferdows, Georgetown University, McDonough School of Business, Washington D.C., USA

In our paper “What to expect from a corporate lean program,” recently published in the MIT Sloan Management Review, we asked a fundamental question for lean managers: How does the performance of a plant change as it continues to implement a corporate lean program? The answer has important implications on how successfully managers can implement lean in a facility. Not knowing it can lead managers to set erroneous targets, have unreasonable expectations, or - worse - take improper action.

Considering all the evidence in literature and industry, there is little doubt that lean can significantly improve the performance of manufacturing organizations (our own research shows that too), but how this improvement manifests itself during the implementation process is less clear. There are several reasonable patterns: if we see lean as a never-ending journey of incremental and continuous improvement, for example, we would expect a linear relationship between implementation and performance. If we think of all the low-hanging fruits that are present in most factories, we could expect a faster improvement early on, which levels off later on. Or, considering the notion of organizational inertia (i.e., wherever there is change, there is resistance to it) we could expect a slow start followed by an exponentially growing performance improvement as more and more people are convinced. Which one it is - or if it is a combination of the patterns, or another pattern altogether - was exactly what we wanted to find out with our research.

OUR RESEARCH

In order to study how the implementation of lean affects plant performance, we examined the seven-year history of the Volvo Group’s Volvo Production System (VPS). The VPS is a typical corporate lean program, which Volvo aims to implement in all its 67 plants, located on all continents. We conducted a large questionnaire survey, had access to unique implementation audit data, visited 44 plants, and interviewed more than 200 employees.

The data for the independent variable (implementation of VPS) came from the audit. The data for the dependent variable (plant performance) came from the survey, the visits and the audit, and were measured using a composite calculation of the plant’s improvement based on four common operation metrics: safety, quality, delivery, and cost. We used regression analysis to reveal the relationships among the variables. Our study was an in-depth analysis in only one company, but we think it can provide valuable insights on how to implement a corporate lean program in any firm. So here is what we found…

PATTERN OF CHANGE

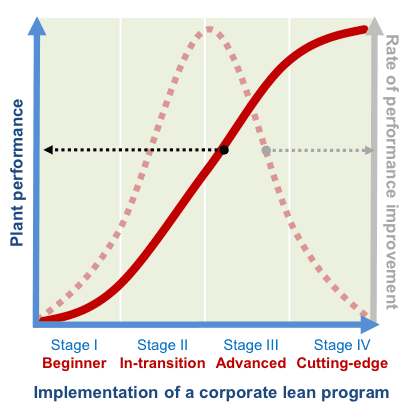

We discovered that implementing a corporate lean program in a factory impacts its operational performance, on average, in a way that can be described by the S-curve: performance improves slowly in the early stages of implementation, then improves rapidly, and eventually returns to a slow rate of improvement. It follows that the corresponding rate of performance improvement follows a bell-curve. Figure 1 illustrates the effect of implementing a lean program on the performance of a factory.

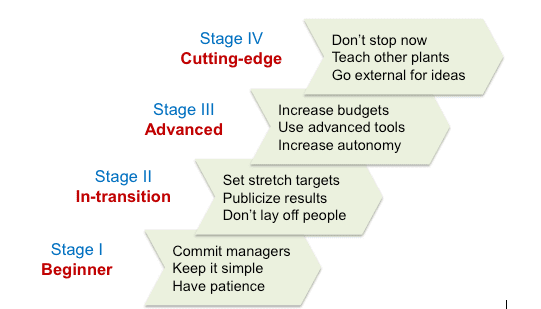

The most important insight we can draw from the S-curve is the following: Plants in each stage should be managed differently. For HQ managers it means to apply different action schemes in factories at different stages of development within the global organization. For plant managers it means to tailor actions for the stage of implementation. We separate the lean journey into four natural maturity stages: Beginner, In-transition, Advanced, and Cutting-edge. Note that plants do not move through the stages with the mere passage of time. To progress is hard work and requires managers to know of the pitfalls and opportunities of the stages. Let us take a closer look at each of them.

Stage 1 - Beginner plants

At the beginning of the lean journey, many managers will instinctively say: "We are different; that corporate lean production system is not for us," "We have tried that before and it didn't work," or "Good idea, but we've already done that." They have good reasons for saying these things. Of course, all factories differ in one way or another. And yes, lean is not new. The related ideas of total quality management and just-in-time production have been around for more than three decades now, and not many companies have been able to completely ignore these concepts. When it comes to lean, the challenge has never been trying, but succeeding with its implementation. Considering the S-curve, and what we have seen at Volvo, we advise beginner plants to:

- Commit managers

- Keep it simple

- Have patience

The plant needs committed managers. However, many continue to "outsource" implementation projects to consultants or let the production manager and his staff sort it out alone. Such plants will not get the benefits that lean promises. At this early stage, it is important to keep things simple. Throwing hundreds of tools and techniques in a Japanese vocabulary at overburdened employees and middle managers is a recipe for frustration. Instead, start in a receptive corner of the factory. Tools like value stream mapping, 5S, and visualization are often sufficient at this stage. Do not expect a huge return on investment in terms of reduced costs, but rather in terms of working environment. Another advice is hence to have patience. There are indeed low-hanging fruits that give a few quick pay-offs, but the real benefits of lean are first realized when the majority of the factory and its supply chain operates according to the principles. Managers who are not aware of the S-curve may erroneously terminate the lean implementation before they reach the harvest periods in later stages.

Stage 2 - In-transition plants

If the plant makes it through the hurdles of stage 1, it can reap some real benefits of the lean program in stage 2. These plants are in-transition from the old way of working to the new lean way. At this stage, many more areas of the plant start the implementation. The experiences in the pilots allow managers to more quickly implement the lean program elsewhere on the shop floor and in the offices.

Skeptics slowly get convinced by the improvements in the pilots and the implementation gets fueled by an increasing number of success stories in the plant. The biggest risk is probably complacency: managers see that the implementation goes well and start channelling their attention and energy in other directions. Instead, what they should do at this stage is to:

- Set stretch targets

- Publicize results

- Not lay off people

Because an accelerated pace of improvement should be expected at this stage, managers should set stretch targets. Managers and shop-floor workers should not be satisfied with the usual level of improvement. The in-transition stage can be an exciting one; low-hanging fruits can be picked along the way and benefits reaped rapidly. New plant-wide meeting structures and quick-response problem solving on the shop floor are typical lean methods that would be very effective at this stage. Managers should take advantage of the improvements by publicizing results to boost morale and encourage people to engage in further implementation. Another essential advice for plants in transition is to not lay off people. The journey towards a true lean factory is still fragile, and can quickly be reversed if people start fearing for their jobs. Instead, use the won resources to assist further implementation, advance the skills and knowledge of the workforce, and grow your business into new markets.

Stage 3 - Advanced plants

Not many plants make it beyond stage 2. Research on change management has suggested that two out of three will stagnate or return to the old way of working before they become "advanced". The S-curve explains why the focus of many managers on the corporate lean program tends to decrease: as most of the low-hanging fruits are picked and the obvious improvements are implemented in stage 2, the rate of improvement starts to decline. Being satisfied with the results already obtained, managers erroneously start looking elsewhere for further improvements. Terminating the corporate lean program at this point is a common mistake. Instead, managers should do the following:

- Increase budgets

- Use advanced tools

- Increase autonomy

Somewhat counterintuitive, considering the declining rate of improvements at this stage, we advise managers to increase the budgets to lean implementation. It costs more to pick the higher hanging fruits. At this stage more advanced lean tools are helpful, and the workforce should by now be competent in using them. Reengineering the logistics systems and using advanced statistics to drive out quality irregularities can help improve the plant further. This is also the stage to increase the autonomy of shop floor teams, which will reduce management resources as bottlenecks for improvement. Managers in such plants can now free up time to assist suppliers and sister plants to start developing the lean supply chain.

Stage 4 - Cutting-edge plants

Reaching the final stage is a natural goal for plant managers, but not an easy one. At this stage the plant is cutting-edge in its industry. As the plant now pushes the boundaries of efficient production, improvements are fewer and harder to find. On the other hand, additional improvements at this stage can win the plant a competitive advantage that will be hard to match by rivals. By strategically leveraging their capabilities, cutting-edge plants can offer products and services that yield higher margins and attract new customers. They should also assist other plants in their lean journey. These plants compete at the world championship level. Again, there is a risk of complacency. In our opinion, managers of cutting-edge plants should keep spirits up by doing the following:

- Not stop now

- Teach other plants

- Go outside for new ideas

Because reduction in commitment quickly leads to stagnation or termination of the lean program, managers should notreduce their level of attention to it, even if the rate of positive effects gets slower. Cutting-edge plants should not stop now. A good plant that finishes improving will also finish being good. Instead, plant managers should stay committed to the lean program and even assist other plants in their journey. Though it might seem like a waste of time for some managers to teach other plants, the pay-off is considerable. By teaching lean principles to supply chain partners and other firms, the managers develop a deep expert knowledge of the lean journey. This is also the time to go external for new ideas: partnering with other world-leading firms and academic institutions can secure advantages not available to others.

CALIBRATE EXPECTATIONS AND STAY THE COURSE

The lean journey extends well beyond a typical budgeting period. In our experience, plants that succeed with the implementation of lean will spend approximately one to three years in each of the three first stages. In other words, a plant can theoretically get from a terrible state to world-class in eight to ten years - but only if managers remain committed and stay the course. Knowledge about the S-curve helps to calibrate the expectations from the lean program and can be helpful in designing an effective implementation process (Figure 2). It is our hope that more managers will use our insight from Volvo to improve the chances of success in their lean efforts.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

PROFILE – Persevering, letting people inspire you and committing to continuous learning. These are the things you need to do to successfully embrace lean thinking and, it turns out, learn to play the violin.

FEATURE – The authors explain why putting value at the heart of customer discussions is key to developing a successful, resilient tech firm.

INTERVIEW – In this follow-up conversation with the Hospital Moinhos de Vento in Brazil, we learn about the elements that are helping them to make lean stick.

VIDEO INTERVIEW – Last year, the Lean Global Network launched an initiative to leverage the knowledge of our institutes to positively impact the healthcare industry. We caught up with the group in São Paulo this week.