Unlocking the secrets of Kanban with Michael Ballé

THE TOOLS CORNER – In this new series, we go back to basics, offering a guide on how to implement some of the most important lean tools and explaining why they are so clever. First up, Kanban.

Words: Michael Ballé, lean author, executive coach and co-founder of Institut Lean France.

Main photo courtesy of Alliance-MIM

WHAT IS IT?

A Kanban is originally a signboard, usually printed cards in plastic cases. Every box of items that flows through a lean pull system carries its own Kanban card. Kanban come off of items that have been used or transported, and go back, as orders for additional items, to the preceding process.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

A card, a “Kanban” (signal), is placed in each component’s container. When a team member takes the first part out of the container – say a headlight cover – he puts the card in a mailbox. The cards are collected regularly throughout the day, and sent back to the supplier as orders of new components. The instruction for the supplier is then to supply one part when they see the customer has used one.

WHY DID TOYOTA COME UP WITH IT?

In its early days at Toyota, Kanban was a practical response to a very difficult problem. In order to follow customer demand more closely, Toyota engineers wanted to make one car – say a model A – only when they’d sold a model A.

On top of this, as they were capital poor, they wanted to make several different model (A, B and C) on the same production line. What is more, they wanted to produce the cars in the order of customer demand.

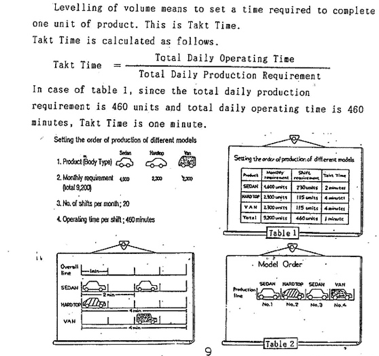

A production line would be scheduled something like this:

For this to happen, each workstation needed all the parts to make every model – the A sedan, the B hard top, the C van. Therefore, they needed very small containers of each part. Components had to be brought to the line according to the idea of “use one, get one.”

The simple yet transformation Kanban cards put tremendous pressure on the entire production system, with far-ranging implications:

- Toyota trucks would go to the supplier several times a day to pick up a few boxes of each component;

- All parts in all containers have to be good: if you have only five parts in a container, and one is bad, this stops the line (you can’t just throw away the bad part and move on to the next one);

- Toyota had to give fairly reliable overall forecasts of production so that the supplier could calibrate its capacity to deliver parts, and Toyota had to learn to pull regularly from the supplier without massive peaks and valleys (which meant scheduling the line as shown in the figure).

- The suppliers are incentivized to bring flexibility to their own equipment by doing more changeovers (practicing a lot of SMED);

- Any delay in building the cars to takt time would create havoc in the supply chain, so team leaders are always on the lookout for team members’ difficulties, to help them stick to their cycle by taking on a part of the job, thus spotting opportunities to improve the flow on the line.

There are three key phases in the use of Kanban (check out the video below to see an example of this):

- A production line no longer works in mass production but in one-piece flow, with each car’s identity summarized in its Kanban card – options, specifications, etc.

- These options are picked up from boxes on the side of the line, when an operator takes the first part from a box, he puts the Kanban in a mailing post.

- This is then transferred to the supplier which makes one box (sell one, make one).

WHY IS THIS SO CLEVER?

Because the sequence of decisions you make matters disproportionately to the final results.

Think of it this way: we’re starting this new series on basic lean tools on Planet Lean. We could have started with a batch, listing all the basic tools. As a “supplier,” I could then choose which one to start with, then the next and so on.

Human nature being what it is, I would start with the tools I’m most comfortable with, and leave the hard cases for later. As a result, I’d write what I’ve always written about.

If we do it using Kanban, we start with, well, Kanban, and once that’s done we ask ourselves what the next tool should be. This might well be SMED, or Standardized Work, not necessarily topics I can easily write about. Since I need to deliver to Kanban, I will then have to face my difficulty and learn how to do it. And that’s kaizen.

The end result will be very different as well, as the list of tools will grow organically, and having solved some early problems with the first attempts, the later ones will be easier to write – kaizen again.

As a producer, working with Kanban completely changes my relationship to the work. I can see, very visually, that 1) I have to deliver a piece of work at a certain tempo (as opposed to plow through a list how/when I can), 2) I have to make every single piece good, 3) I can’t choose in advance the parts I like and leave the tricky ones for later (I need to face every issue now), and 4) I probably need a “chain of help” to get me out of real difficulties when I’m stuck.

SO WHAT?

Sticking to Kanban will open up the real potential of kaizen:

- Problem solving – how do I solve concrete problems in order to deliver my Kanban in the required time?

- Lead-time reduction – how can I reorganize myself to deliver quicker on the Kanban when it arrives? (Like any producer, I’m a batch worker and tend to accumulate kanbans and then do them all at once because I’m not that flexible.)

- Value improvement – what I learn by solving the points 1 and 2 above shows me wider possibilities to do the job much better, with greater quality for customers and at a lower cost for me by eliminating waste.

The spirit of kaizen is to bring value closer to the final customer. Without Kanban, you can be practicing what you believe is kaizen, but you actually have no compass, no direction-setting, practical, visual, here-and-now tool to see whether the new idea is a step in the right direction or just a random change.

Before calling it the Toyota Production System, Toyota engineers used to refer to their improvement system as the “Kanban system”. There’s only one conclusion: if you’re not using Kanban, you’re probably doing something great and improving things here and there, but you can’t call it “lean.” Kanban is a harsh discipline, but it’s the first step into the bigger world of true continuous improvement.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – Fresh of a study tour in Japan, the authors wonder if there is anything left to learn from Toyota’s network of suppliers in the age of AI and digital. Hint: it’s a rethorical question.

FEATURE – Until “check” and “act” become a natural part of daily work, we will always need formal audits to keep people focused and to sustain results. Here’s a few tips to make them work.

INTERVIEW – Italy-based precision machinery manufacturer Sisma has changed skin many times over the years. We sat down with its general manager to learn how the firm has been able to continuously innovate over the years.