Understanding the context of your process

SERIES – The authors discuss the first of six elements in their process development model – Context – highlighting the importance of gaining clarity on the objectives of the process being created.

Words: Eric Ethington and Matt Zayko

“Any fool can know. The point is to understand.”

Albert Einstein

16 SECONDS

The conversation went something like this:

Product Engineer: “The customer is requiring a new in-line pressure test for all parts.”

Lean Manager: “When will it be implemented?”

Process Engineer: “We have a design that we can pilot in four weeks.”

Lean Manager: “And the cycle time of the test is 16 seconds.”

Process Engineer: “No, actually it’s 30 seconds.”

Lean Manager: “Sorry, I wasn’t clear. That wasn’t a question, it was a statement – the cycle time is 16 seconds.”

Product Engineer: “We have to do this. It’s a customer requirement!”

Lean Manager – “Having the test is a customer requirement, the cycle time is up to us and it has to be 16 seconds. We’ve spent a year improving our lines, balancing the ten stations to within a second or two of 16 seconds. You are not putting a 30-second test in the middle of the lines, or anywhere near them.”

After the engineers mope away, the Lean Manager wonders: “Although we dodged that catastrophe, how do we avoid conversations like this in the future?”

COMMON FAILURE MODES

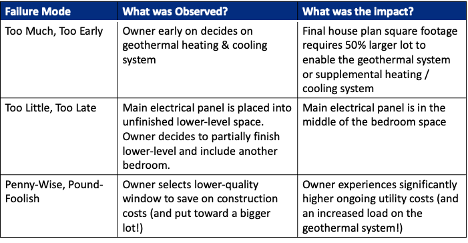

If you have ever been involved in developing a new process, you know that problems can manifest themselves in countless ways. In our book The Power of Process, we introduced three general failure modes related to decision making that drive many of the problems that appear later in the development cycle:

- Too Much, Too Early (TMTE): Critical operational decisions are made too early with incomplete knowledge or input.

- Too Little, Too Late (TLTL): No upfront process thinking and limited process design for new products before their final design.

- Penny-Wise, Pound-Foolish (PWPF): Functional or area decisions are made that may lead to local optimization but frequently lead to overall performance reduction.

To further illustrate these failure modes, here’s a more generic example centered on building a house:

Of course, identifying failure modes and their impact is not the point. We need to put our energy into avoiding these failure modes in the first place.

CONTEXT AS A COUNTERMEASURE

Context, the first lens of the 6CON process development framework, provides the development team with critical information against which they can readily make informed decisions. Context, by itself, does not eliminate the failure modes we have mentioned, but it is the foundation for the rest of the work to come, reducing the likelihood of the failure modes. The components of a well-crafted context vary by organization and can even vary by project, but here are a few we have used that we would encourage everyone to consider.

Stakeholder Needs

The identification and alignment around stakeholder needs will provide guidance throughout the development of the new process. All programs have, at a minimum, customers, investors and employees. After the program launches, how will each judge success? For example, a customer may be looking for value delivered on time, at a high quality and at a fair price. The investors are most likely expecting a return, while the employees are looking for some sort of security as well as on-the-job fulfillment.

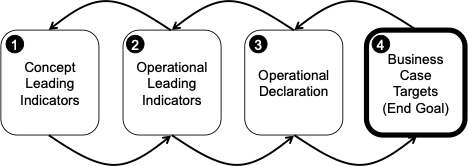

We have found it useful to think about stakeholder needs from end to beginning, but execute against the needs from beginning to end. For example, what does on-time delivery look like to the customer after launch? It could be receipt of the exact product 5 days after it is ordered. What does that same metric look like two weeks before the program is launched? It might involve testing the value stream where the lead-time from the order point to the dock is 3 days and the shipping time to a given destination is 2 days. What might that look like six months before launch? It could be equipment is meeting cycle time and quality targets. And so on, right up to the initiation of the program. This chain of needs can be used to create scorecards for determining the readiness of the program and provide guidance when choosing between process alternatives.

©2021 Ethington / Zayko :The Power of Process, Productivity Press

Operational Declaration

The Operational Declaration (OD) is ideally a subset of the product development Concept Paper. The Concept Paper is a document that aligns a team around a vision, scope, and direction for a new product. If your team does not have an overarching Concept Paper, you can still create your own OD from scratch and work in the longer-term to integrate both product and process development with a Concept Paper.

Many organizations have scoping documents or project briefs, but the OD is not the same as these. The OD is a document of operational knowledge that improves with experience, and once you get to the Configure lens of the 6CON framework, the OD becomes a “contract” to execute. The OD is often divided into critical categories with detailing statements such as:

Quality or High Built-in Quality:

- No on-line rework. Defects will be quarantined and tore down in a central area. Components determined to be OK will be returned to the production inventory.

- There will be no receiving inspection. Suppliers must be self-certified and provide appropriate documentation.

Schedule or Value On-Time:

- Central supermarket to be used to store all purchased parts.

- Fork trucks will only be utilized in the immediate dock area. All materials moving from the supermarket to the line will be delivered via tugger routes.

Cost:

- Operational Availability (OA) goal is 85%.

- Work-in-Process (WIP) levels shall be clearly defined between processes.

- Preparation of materials for optimum parts presentation will be done in the supermarket.

Safety:

- Workstations will be designed to minimize operator motions outside of the 13”x13” value-added zone.

- Safety-related incidences, near misses, and observation findings will be tracked and continuously improved.

Engagement:

- 100% of standard work design and documentation will be developed by the team members doing the work under the guidance of a team leader or support industrial engineer.

TAKT TIME SCENARIOS

We find takt time to be on of the most talked-about and least understood concepts in lean. Although we might dig into it more in a future article, for now let’s just remind ourselves that it is not a firm number. Just think about the numerator (total available time) and denominator (customer demand) – both are variables, so the result is also a variable. Regardless, we do find that it can be helpful to develop a set of takt time scenarios so we can understand the range of takt times we may be dealing with. One idea is to create a matrix and calculate takt times for 1, 2 and 3 shift operations against the nominal projected volume, 80% of nominal and 120% of nominal. Again, this exercise will vary by business. Some processes must be 3 shifts, others can only be 2 shifts. The point is to consider various scenarios, look at the resultant takt times, and think about how you might design your system to be able to produce efficiently at a variety of likely takt times.

LEMONADE FROM LEMONS

The “near miss” of the imbalanced test station featured at the beginning of this article turned into a positive. It inspired us to establish our own version of “Context”, although we didn’t call it that at the time. It wasn’t that hard to do: it started with an analysis of the range of takt times and included a list of best practices, or lessons learned, from our process experience. Was our first attempt perfect? No, but it gave us a standard to reflect and improve upon. This same logic was applied to thinking about stakeholder needs and how to represent them at the various stages in the development of the new process.

For more details, please visit www.thepowerofprocess.solutions

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – What does it really mean to teach lean? The author reflects on this question and shares a few tips on how to successfully engage learners in different environments.

CASE STUDY – The CEO of a hospital in Johannesburg looks back to the last five years to reflect on a lean healthcare transformation that is creating positive outcomes for patients.

FEATURE – To really embrace lean thinking means to ensure the bureaucratic structures in our organizations enable our people to excel, rather than constrain their creativity.

VIDEO INTERVIEW – We recently caught up with John Shook at the Lean Healthcare Academic Conference in Stanford and asked him to share his thought on the questions we need to ask ourselves in a lean journey and on lean in turbulent times.