Why dialogue, and not discussion, supports real innovation

OPINION – It might seem like a subtlety, but the distinction between discussion and dialogue is actually fundamental as we try to find new ways to unleash organizational creativity.

Words: Boaz Tamir, President, Israel Lean Enterprise

I recently had a thought-provoking conversation with a development engineer who had just declined a promotion to a managerial role.

"I don't need the respect and status that come with a managerial position," she told me. "I am fascinated by the process of discovery, development, research and problem solving. In the lab, I can push the boundaries of current knowledge. I have no interest in political power games, in having to explain a hypothesis that was disproved by an experiment, or in facing criticism that isn't based on facts or an actual understanding of the cause of a problem."

She seemed to be particularly skeptical about meetings and conference calls, which are routine for managers, saying she found every minute spent away from her working station a minute wasted. She went on to mention meetings in which big statements based on untested assumptions are used to address complex issues; in which people are terrified of their managers as if about to stand trial; and in which discussions generally lead nowhere.

Anyone who has ever participated in managerial discussions (or a military assessment) will find it difficult not to agree with her.

And yet, the fact that she preferred to lock herself up in a laboratory made me think. I couldn't get my head around it: product development is the result of a collaboration of many – hundreds, if not thousands – individuals. Isn't it necessary to have an exchange of opinions in order to understand the context of the solutions that we are supposed to come up with? What about constructive criticism? Isn't feedback crucial? I found myself asking her: "Can you give it all up? Can you really work in a bubble?"

She gave a resigned look and told me, "Quite the opposite! I'm dying to talk to my colleagues and think with them. I find myself exchanging opinions with people by the coffee machine or in the bathroom, but it's hard to find a place where we can have structured discussions, where we can share our experience and knowledge."

Bringing in a range of professional disciplines and creating a thinking community might be a necessary condition for developing technological innovation, but the truth is that most organizations lack the skills, tools, and managers to create a space for creative thinking. "A place to put together all the pieces for systemic thinking within a thinking system," the engineer told me.

THE POWER OF DIALOGUE

At that point of the conversation, I thought of David Bohm, the social philosopher and physicist who believed that dialogue creates a space for people who represent a variety of opinions, perspectives and ways of operating to meet and work on finding a solution to a problem, together. By its very nature, dialogue (as opposed to discussion) sees debate and clarification as the essence of discovering the truth – which makes the hierarchy typical of traditional decision-making structures unnecessary.

Discussions certainly enable participants to influence decision-making: they are seen as an organized way to make a one-dimensional choice on how to solve a problem, following a thorough analysis of the situation. The selected solution provides a sense of direction and control, but at the same time requires us to ignore unexpected points of view, possible alternatives, and the value of multi-dimensional examination. In truth, decision-making in hierarchical organization is often based on assumptions, stereotypes or past experience.

Unlike discussions, dialogue wants to clarify the nature of the choice within an open array of possibilities: equal weight is given to the ideas and thoughts of all participants in the dialogue, and the process unfolds as insights and critical and skeptical thinking is brought to the surface. Dialogue seeks to investigate and understand the context and basic assumptions that serve as the basis for the speaker's arguments, while pushing towards a synthesis that is the best solution out of the suggested options.

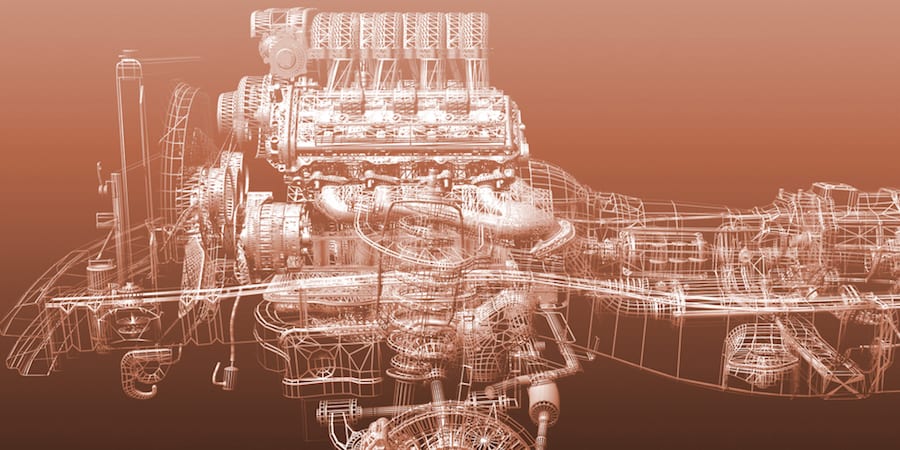

Allen Ward, a leading lean product and process development thinker, developed a managerial perspective on how to approach product development, based on the idea of dialogue: set-based concurrent engineering (SBCE). Under this methodology, the development team attempts to find and define a solution as the combination of a number of adequate parts.

SBCE is based on systematic problem solving and PDCA. The teams engaged in this innovative process must be equipped with both lean problem solving skills and the ability to systematically interact with the program management. In SBCE, the Chief Engineer represents the voice of the customer, while the different functional units advocate for different disciplinary and technological viewpoint.

The transition from discussion to dialogue is characterized by four principles:

- Trust is a necessary condition for conducting a dialogue: traditional organizational hierarchy should be ignored.

- The conversation is conducted through the presentation of open questions and the active listening of each and every speaker.

- The difference between concepts – such as thoughts, assumptions, and definitive knowledge – is important. Facts are determined only through empirical proof.

- Arguments are to be avoided. If the group is not skilled at keeping to the rules, it is recommended that it take on a seasoned facilitator, who is not to intervene in the direction or content of the dialogue.

"The transition from discussion to dialogue can be compared to the transition from a game of ping-pong to a game of paddleball," I suggested during my conversation with the engineer. "In the former, each player tries to make the opponent unable to respond; the latter is based on teamwork, because both sides win or lose at the same time. That's the direction our organizations should take."

The traditional "waterfall" hierarchical product development system cauterized with the habit of holding cross-functional integration meetings in conference rooms might be hard to eradicate, but change will come naturally as the next generation, which fully understands the advantages of collaborative cross-boundaries dialogue over discussion, comes in and lead us towards change.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

INTERVIEW - To really change, an organization must use lean management as a strategic asset rather than just a set of tools. In this interview, Art Byrne talks about rewarding people and the process of transforming companies.

OPINION – Our systems to develop new products are slow and inadequate for the ever-changing markets we have to work in. The author describes the three lean elements that will unlock your potential to innovate.

INTERVIEW – A 22-people veterinarian hospital in Barcelona has recently turned to lean thinking. We caught up with the owner to learn how things have changed six months into the journey.

NEWS - Our institutes in Turkey and Israel have collaborated closely for years. A few weeks ago, the President of Lean Institute Turkey flew to Tel Aviv to learn about Israeli agriculture.