Visuals all around us

FEATURE – Visuals are a natural way in which human beings learn and teach. The author discusses why visual thinking is part of our DNA and the implications this has on our lives at work.

Words: Sharon Visser

Every day, the Earth provides us with information in the form of visuals. The sun rises to mark the beginning of a new day and sets to announce it is ending and night is coming. Similarly, the leaves falling off trees are a sign of the autumn and shoots growing one of spring springing.

Indeed, some of the best visuals known to humankind are created by the Earth itself, telling us where and when we are. Upon seeing such impressive visuals, we can’t help but ask ourselves questions, like “Are we ahead or behind?” – as if a sudden urge to ensure we are in sync with the natural cycle of things came upon us. Do we have enough heat for winter? (That one’s particularly topical, giving the energy crisis.) Do we have enough water until the next rains fall?

These visuals also have something of a mystical power over us. That’s why, for example, scores of people gather in New England every year to watch the fall foliage change colors. Or why Japanese people flock to parks every spring to joyfully welcome the first cherry tree blossoms (they call it “hanami” – or “flower viewing”). Or why we can’t seem to resist a sunrise or sunset and simply must stop and take a picture of it.

Because they are a part of every culture, we teach these visuals to our children, from generation to generation, so they will become able to see and then question.

It has always been this way.

We have been using visuals for centuries to teach and mentor our young, but also to enrich our learning experiences. We have come to do this instinctively because we know it works. This learning experienced that master and learner share gives the former purpose and the latter skills (while giving them both respect).

Let me take as an example of a very old skill, the tracking of an animal to provide food for a family or clan.

My husband is a skilled tracker. Having grown up on a cattle ranch in Botswana, in the middle of the Kalahari Desert, he started to learn this skill at the age of five from a San elder. He learned by following the tracks of a tortoise with the other San children he played with.

The San people consider a tortoise a suitable place to start to learn: it is harmless, easy to identify, and slow enough to find and confirm.

As the tracks of the tortoise were identified and followed, what the tortoise was doing became the subject of the discussion – how big it is, when it stopped to rest, where it turned around, how it navigated a log, what it ate, when it walked fast and when it got a fright and withdrew into its shell. When the tortoise was found, it was fully observed by all the children to confirm that the tortoise was all that they thought it was.

This lesson continued whenever a new tortoise track was spotted, until the children could do this by themselves and translate the information correctly, bringing the tortoise back to the elder and telling him its story. The elder would then follow the tracks with them and see how well they understood the story.

Once they got the tortoise covered, they could move on to other, more challenging animals. This is nothing more than learning by doing under the guidance of a master. The visual (the tracks) was not the goal: what mattered was what the visual told the children about a certain behavior.

Note that this is complex learning, with many variables, and that any change in the visual reflected a different variable coming into play. The first step is the correct identification of the track itself and of the animal that it belongs to. By following that track step by step, it is possible to formulate hypotheses on why it has changed and then confirm them or discard them.

It's important to understand that the variables are part of the tactic knowledge learning – things like the terrain type and soil consistency and how they impact the visual of the track. The weather, wind direction, and time of day are also considered, as all these factors are part of the instinctual behavior of the animal itself and, therefore, come into play and further shape the track. Such tactic knowledge requires the use of many of our senses, like touch, hearing, and smell.

Given all this, it is not far-fetched to assume that, in a business, every time we provide visuals about the work, we are really calling on a thread that tugs on our people’s DNA – no matter where we might be in the world.

Visuals allow us to see the work, discuss it, and find our way forward. They speak of the behavior of our organization. They are where the master asks the questions that stimulate the learning and problem solving of their students. When this is done, skillsets improve, and collaboration and engagement naturally blossom.

In the digital world, we have so many ways to learn – often on our own – and they can all be very helpful. Yet, within every learner lies a longing for the stimulation of the master and the companionship of engagement, in the hope that one day we too can become masters and share with our learners. That something is there, within our DNA, just pulling on that centuries-old thread and, ultimately, pulling us forward. It’s the way it has always been.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

FEATURE – By offering an alternative approach to management, lean thinking has disrupted the business world in the past three decades. But in what way has it really innovated?

CASE STUDY – This Dutch company awards social benefits to the unemployed. Thanks to lean thinking, they were able to radically transform the service they offer them.

FEATURE – Lean coaching is all the rage these days, but to what end? The author reframes the role of a sensei as an expert in achieving productivity by engaging everyone in kaizen.

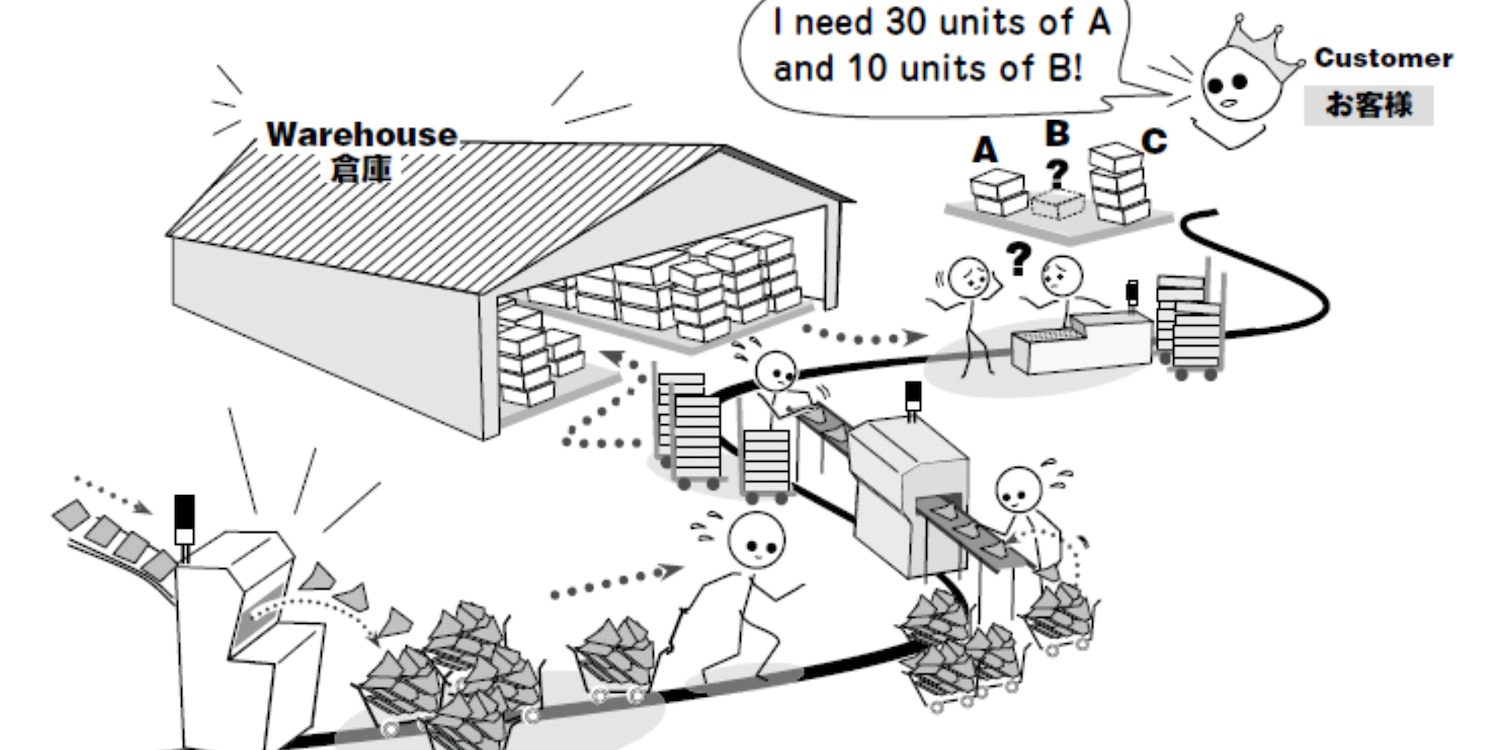

FEATURE – The release of Christoph Roser’s new book All About Pull inspires John Shook to discuss the origins and true meaning of “pull” and why it is incorrect to blame JIT for the shortcomings of global supply chains.