Raise the bar on yourself

FEATURE – Based on their experience supporting the stellar growth of Aramis Group, the authors discuss the role of leaders in shaping minds and behaviors and constantly challenging themselves to be the best example they can.

Words: Michael Ballé, Nicolas Chartier, Guillaume Paoli, and Régis Medina

Our book Raise the bar- From zero to 1 billion shares the lessons we learned growing the Aramis Group up to its IPO on the Euronext stock exchange. The title itself summarizes our main insight, with a catch. It is easy to interpret it as “increase expectations of others”, but our main learning is the importance of raising the bar on oneself. The balance of securing today’s performance and adapting the company to tomorrow is a constant test of leadership, and as customers, markets, and the world evolve, there are no set answers. Best practices can inspire and make you look at your own situation differently, but in fact, they don’t help: they are yesterday’s best practices, and what we need to figure out is where things are going in the coming years.

We were taught that scaling up a company was all about structure and processes. Structure as captured on an organizational chart: specialized departments strung together through a hierarchy. Each department head is tasked with running her department according to budget objectives from above as well as making the necessary investments to adapt it to present circumstances and, in the best-case situation, to the future. Processes are mostly rules about how to do things in order to get a repeatable result. Work is, in general, seen as prescribed. Set actions are part of the process, which is constantly optimized to benefit from economies of scale or automation.

The assumption is that if we set the right structure, which we drive through the right processes, we will achieve on-going performance. Following this thinking, when things change we need to restructure to adapt to new market conditions and redesign processes. Consultancy has become a full-fledged industry to take organizations through these changes. Yet, are these assumptions true? Or have they become an ideology, a program that must be put in place regardless of its consequences?

If we look back at the twenty years since Aramis was founded, we can’t really see hordes of thriving organizations. What we do see is multinationals dominating their markets through sheer financial power, increasingly questionable service to customers from inflexible digital systems, and disaffected employees lacking a clear mission and with sometimes meaningless jobs where they feel like nothing more than a cog in a red-tape machine. Within the structure and process perspective, if customers complain, they expect too much. And if the process fails, it has to be the employee’s fault. In this mindset, processes are the solution and people are always the problem (why can’t they just follow the process and be happy about it?)

In the early days of scaling up the Aramis business, selling new and second-hand cars over the Internet, creating structure (new roles and departments and organizational charts of who reports to whom) and setting processes (with detailed maps and instructions) was also our approach. But as complexity increased and we felt the company was becoming increasingly rigid and irresponsive to clear challenges, we learned to go to the gemba to see problems for ourselves and investigate causes.

On the gemba, you hardly see structures or processes. What you do see are people and systems. People respond to other people’s requests and do so using systems. Both people and processes are specialized, so at some point, there is a handoff, the sequence of which creates a process. For instance, in our case of selling cars through a website, the salesperson talking to the potential customer is unlikely to be the same person who unloads the car from the truck when it arrives or who prepares it for the customer to take delivery. One can imagine such a small sales point that the same person would do all three jobs, but with size it makes sense to specialize.

This specialization, however, breaks the smooth, continuous flow of customer experience and work and creates endless friction points at process handoff areas. Sales staff are constantly juggling the special needs of the customers sitting in front of them and the instructions from their own hierarchy (often expressed concretely as incentives to sell this or that). Preparation staff deal with schedule changes, whether from customers or logistics, and unforeseen issues on the car that can or cannot address on their own. And as processes segments are desynchronized, employees easily get into conflict over who was supposed to do what, who did what wrong and who is to blame for each mishap.

The second lesson of the gemba is that performance doesn’t come from perfect processes but from engaged, inquiring people. Some teams handle perfect hiccups smoothly, taking care of customers first and helping each other in the overlap areas to come up with the “least worse” solution to intractable problems. They handle contradictory priorities wisely and have each other’s back. Other teams, on the contrary, seem to take every task and responsibility in its narrowest sense, get in each other’s way, and seem to enjoy playing the blame game. It’s fascinating to see the sudden negative impact a single sullen new joiner can have on a high-performing team – it’s all about people.

It’s all about people’s judgment, to be precise. Organizations are full of contradictions because no structure or process can be designed perfectly for the current market conditions – and these change faster than organizations can change. But some people, both leaders and employees, handle these contradictions better than others. They understand the priorities, and make the right choices so that everyone enjoys the experience. We’ve seen some customer service agents turn customers that were angry over a very real process failure on our part into enthusiastic promoters: they listened, they empathized, they compensated. Yes, it would have been better if the problem had not occurred, but the skill and emotional intelligence of the customer service staff can make all the difference.

Just as it’s considered common sense that organic growth should be sustained by structure and processes, usual business thinking posits that to successfully grow by acquisitions, you should quickly deploy the same systems everywhere and then recoup synergy costs by centralizing the running of these systems in shared support centers. This theory still prevails although the success rate of acquisitions remains abysmally low. Looking at it from the gemba, we realized that what makes people and team perform is their relationships with their tools. When they understand their tools and systems, how they work, what they show, and what biases they have, they make sound decisions. Change the system for them and they need to learn a new one from scratch – often unwillingly.

Rather than imposing single systems on our acquisitions – just as with harmonizing structures or processes – we’ve take a different, gemba-based approach to integration (by the way, we seldom speak of “acquisitions” and “integration” internally. We rather speak of “joining the group” and “working together”. We know that words weigh, and we’ve found it easier to preserve and enhance staff commitment). We’ve focused on the people. First, we regularly discuss with leadership teams the key lean problems of our business: what really satisfies customers in each culture? How do we purchase the right car at the right time to keep lead-times and inventories low? How do we avoid overcosts by focusing on quality and getting closer to right-first-time? How do we make sure tools and systems work for every team member wherever they are? And with each of these problems, how do we involve team members in recognizing the problem and finding local solutions?

Then as frontline teams get to grips with these typical problems we get them to share their experience and local countermeasures through company-wide communities of practice where people discuss their perspectives, insights and initiatives. With such communities of practice, we see people from different cultures and different backgrounds progressively converge and build together a common understanding of how to best run the business. This, in turn, spurs a natural convergence of systems and tools, as systems evolve in the same direction and tools are shared across the company. The synergies we seek are those of better judgement shared across the business, in different local circumstances and with people with different track records, but progressively buying into the same theory of success.

How can you encourage better judgment across the board? This is the core leadership question. Structures and processes won’t help. Good judgment is a matter of interpretation, of seeing the facts differently, often in the light of experience, and making the sensible choice – not necessarily the prescribed choice. Judgment also means risk taking. It means putting oneself forward to correct a process failure. This, in turn, means risking blame from the structure, that easily sees its role as enforcing compliance, not serving customers.

On the gemba, you realize that your overall performance is very linked to these magic moments when someone has the right insight and takes the right initiatives, which saves the moment. Then you also realize that in terms of fixing processes, you need the same good judgment from people to come up with sensible kaizen ideas – which then can be developed into full process improvements. What you also discover is that such insights and initiatives are mainly born out of conversations within teams. When they have the right conversation, they’ll do the right thing. When they have the wrong conversation (or no conversation at all), they won’t.

To understand the people and systems view, we have come to look at relational protocols – the social norms that guide how people interact with one another and with the systems in place. Such protocols are as affective as they are cognitive: who can easily speak to whom? About what? On what tone? What kind of emotions are considered normal or abnormal within the team? For instance, is frustration or anger part of the relational protocol and frequently expressed, or is it sign of an abnormal situation that needs to be addressed? Similarly, is willingness to help and expressing satisfaction at work part of the relational protocol or are they rare events? As regards to kaizen, are suggestions encouraged and followed-up, or frowned upon and ignored?

These relational protocols cannot be set by either structure or process, no matter how hard structure and process advocates try to do so. They are purely human interactions, ways of relating with each other, and have a strong emotional component. For instance, the degree of trust carried over by the protocol, or the feeling of togetherness versus being adversaries, are emotions. Furthermore, as the company grows across cultures, what constitutes normal and abnormal emotions varies across countries.

Leaders – as we’ve learned the hard way – have a disproportionate impact on such relational protocols. Someone brings you bad news and you react with anger, maybe directing some to the bearer of the message? People will conclude that it is okay to react angrily to bad news. You express frustration because an issue is not getting resolved or not handled the way you’d like? People will think that frustration is ok in their interactions with others, and so on.

Raising the bar for ourselves means understanding deeply what Isao Yoshino, a Toyota sensei, described to us in Japan as “showing your back”, understanding that, as leaders, everyone is always looking at your back while you’re looking elsewhere to see how you react – what is considered “ok” or “not-ok” in reacting emotionally to situations.

Essentially, raising the bar means to be more patient with people on the shop floor describing their activities until we discover the real knowledge point; to react with greater equanimity when we’re told of something, yet again, not working as expected; to be more generous with validation and thank employees more frequently for doing a good job. It means taking responsibility for these invisible relational protocols that underlie every interaction in the company and, ultimately, real performance – as well as our own capability to adapt.

People are the solution, processes are the problem. Practicing lean for years on the gemba has taught us as much. What makes lean lean, we’ve learned in Japan, is neither the bureaucracy of it nor the systems of the company, but the elusive kaizen spirit that some people get and some don’t. The feeling that when something goes awry you ask yourself what you could have done better before blaming someone else. The relentless look for muda and unnecessary work, and the effort to engage people in finding new ways to eliminate it. From this point of view, the elements of the TPS – customer satisfaction, just-in-time, reacting at every defect, leveling workloads, studying standards, trying kaizen, developing mutual trust through stability – are all relational protocols on how to deal with customers, logistics, hierarchy, workloads, procedures, problem solving, or systems.

Each element of the TPS provides opportunities for kaizen, by visualizing a clear challenge, such as better responding to customers, reducing lead-times and so on. These opportunities can be seized or ignored. As leaders, it is our job to create the kind of culture where kaizen comes first and is a positive emotion people experience together (the pleasure of bringing value closer to customers). This, we now know, will not happen on its own, unless we ourselves demonstrate it and shape it. If you want a leaner company, you must be the change you want to see happen.

Get your copy of Raise the Bar here!

THE AUTHORS

Read more

FEATURE – How Lærdal Medical was able to enthusiastically restart its lean journey with help of a good old-fashioned Kaizen Week.

VIDEO INTERVIEW - At last month's UK Lean Summit, we sat down with Dan Jones and Jim Womack, founding fathers of lean thinking, to discuss the evolution, current state and future of the methodology.

INTERVIEW – The CIO of a French pharmaceutical company gives us a sneak peek of her presentation at the upcoming Lean IT Summit, focused on using the obeya to change the IT department.

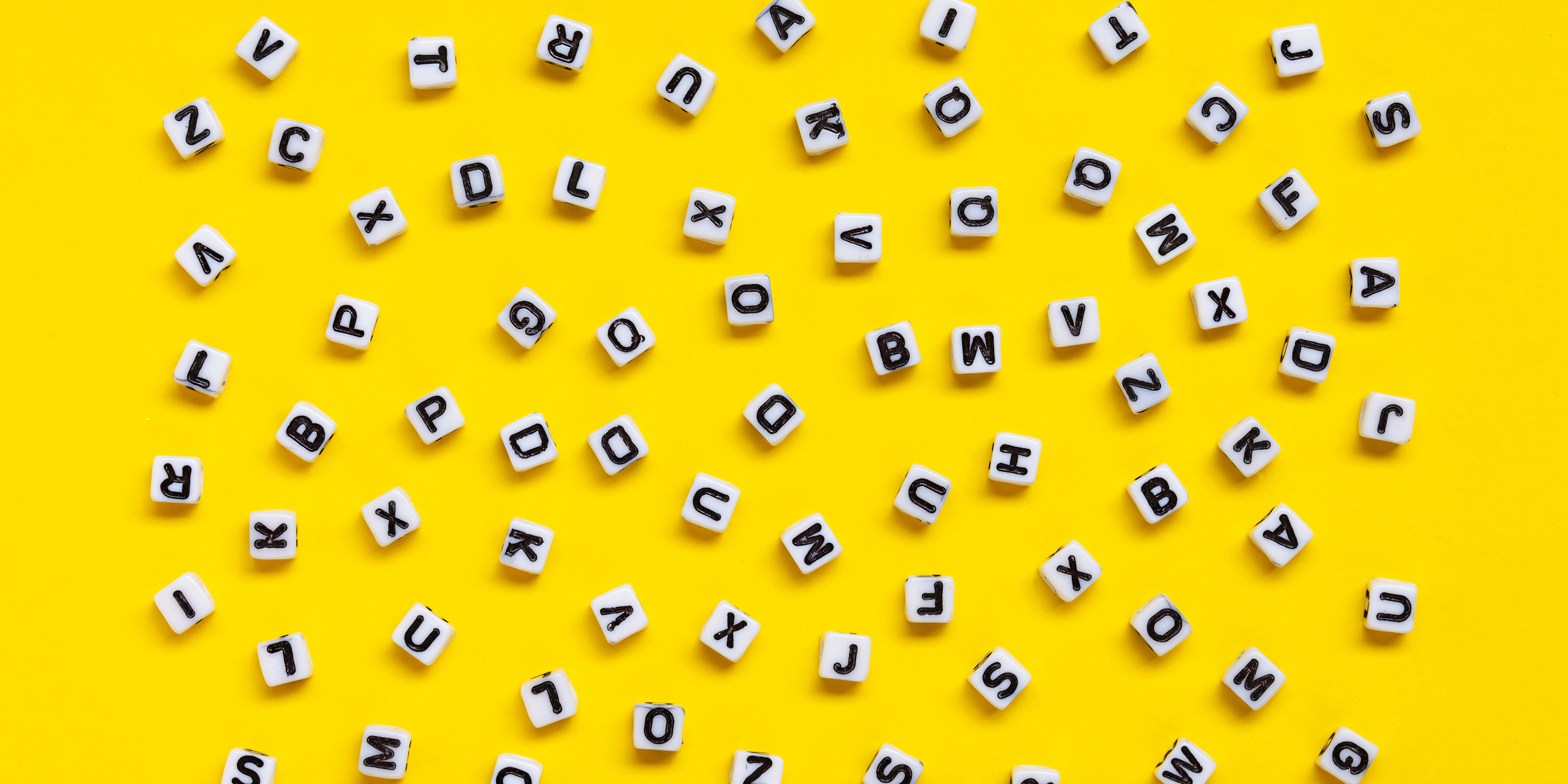

FEATURE – In the lean world, we are used to acronyms and abbreviations. But what’s the value of words if their meaning is lost and fails to reach those we are communicating with?