Why fixing the little problems should not be discounted

FEATURE – A broken phone or a clock showing the wrong time may seem small details to you, but they actually make people's jobs more difficult. Fixing these issues improves work and boosts morale... It also says a lot about you as a company.

Words: Ian Glenday, lean coach and author

There is a word in British English that doesn't have a direct translation in many other languages – and it is indeed unknown to most people in English-speaking countries outside the United Kingdom. Many of you will not be familiar with it. That word is "niggle".

A niggle is a small thing that irritates or annoys us. In my experience, niggles are always present in the workplace but, precisely because they are only little things, they rarely get much attention.

Since "niggle" does not occur in many languages, people often give these little annoyances other names. In Kimberly Clark USA, for example, machines and equipment (commonly known as "assets") niggles are referred to – with a certain sense of humor – as "a pain in the asset". In Poland, the name they came up with for niggles is "peas". It comes from Hans Christian Andersen's literary fairytale The Princess and the Pea (the famous story of the princess who could feel a pea hidden underneath the stack of mattresses she was sleeping on).

Whatever you might call niggles affecting your organization, it is important to identify them and fix them. Doing so will eliminate people's stress, frustration and tiredness. In fact, it will make them happier – and happier people, generally speaking, work better. One cannot always show there is a direct link between fixing niggles and increasing efficiency, but that should not stop our efforts to eliminate these irritations.

Typically, tackling niggles is best done during an "event" rather than as an ongoing process: doing it as an activity during a "lean event" or workshop will help you to keep the momentum going. Niggles are normally the prerogative of a sub-team comprising five or six people: area operators, a mechanic, a manager and someone who is not familiar with the area (this is the person who can ask the "stupid question" - why things are done a certain way).

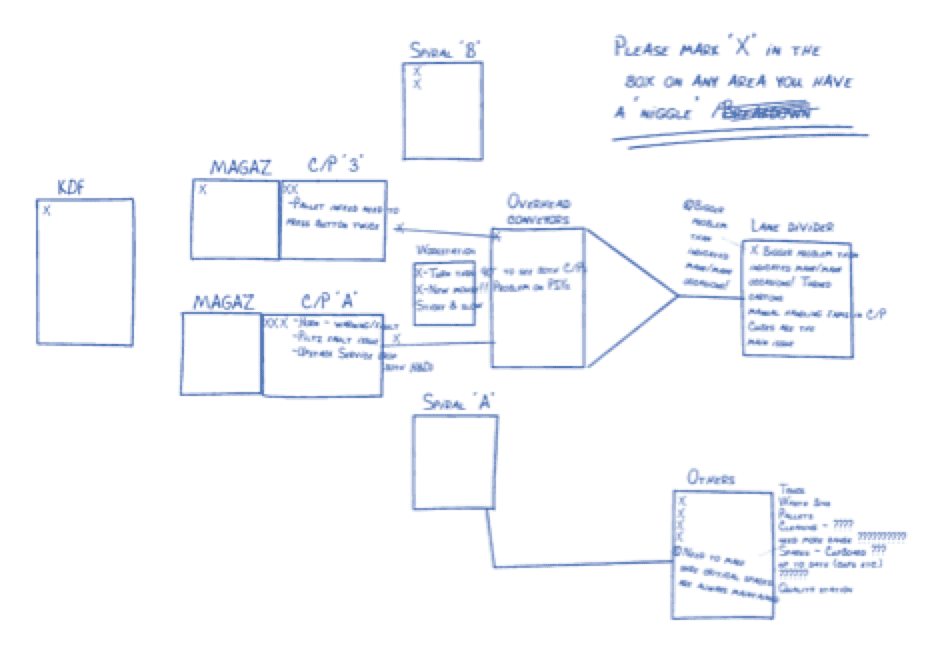

The first task is to identify what niggles there are, using a check sheet – a simple diagram of the area in question. People are then asked to put a cross wherever and whenever a niggle occurs. They often add comments, too. The sheets are then put up in the area and left there for a few hours (or overnight if there is a night shift). The check sheet – an example is showed below – is an easy way to record niggles and helps us to see where they are most occurring.

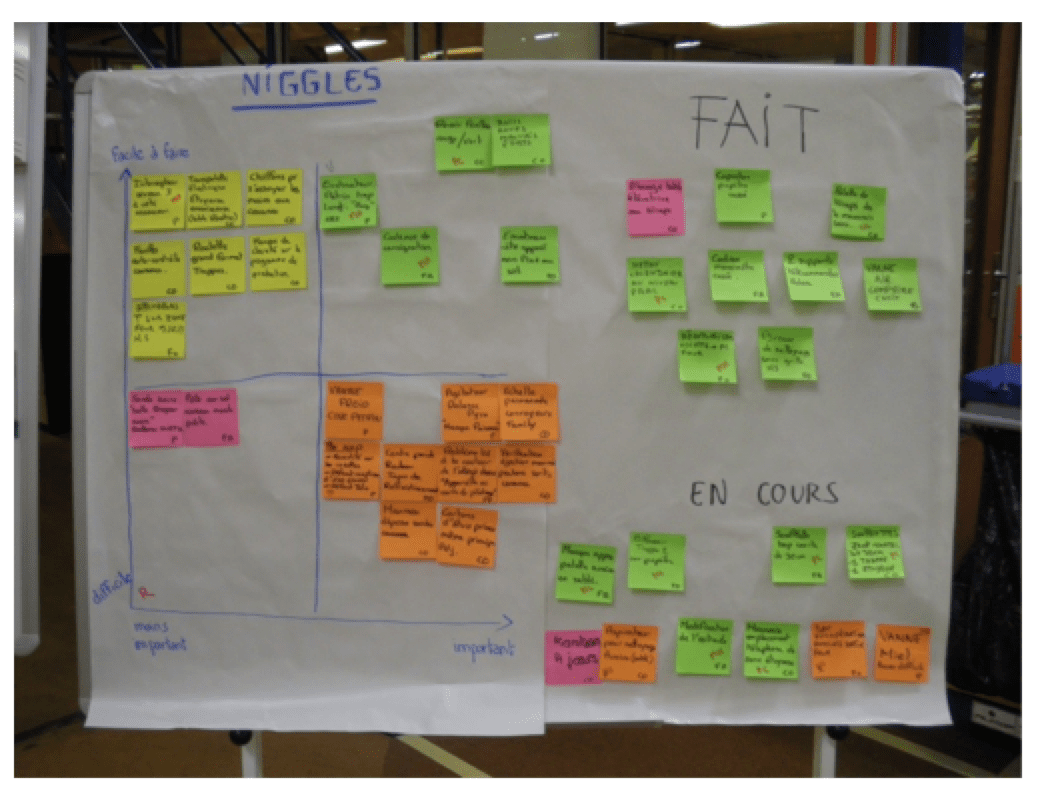

After leaving the sheets up for a while – certainly less than a day – the sub-team goes back to ask people to explain why the crosses are there. It is not uncommon to find anything from 50 to over a 100 niggles. The target for the team is to fix at least 50% by Friday that week during the rapid implementation workshop. People working on the niggles team usually find this target unachievable, at least at first. At this point, it is up to them to decide the strategy they want to adopt to eliminate the niggles. While they work on the goal, they must also communicate to the area concerned the progress they are making. One niggles team at a factory in France came up with a clever way to categorize niggles and communicating progress, shown in the photo below.

Each niggle was written on a post-it. The graph had difficult/easy on one axis and low/big impact on the other. The color-coding was then added to emphasize each category: green means easy to do with big impact, while red means difficult to do with little impact ("en cours" means "in progress"; "fait" means "completed"). This display board was put up in the area were niggles were being tackled.

The team normally has a great week, because of all the positive feedback they receive from people for whom niggles are being fixed. They also finish the week exhausted as they frequently work harder than ever before to fix as many niggles as possible – and they always exceed the target of 50% in one week.

Experience shows that one does not have to spend too much time explaining what niggles are for people to be able to highlight them. They know very well what the little irritating things are, as they have to put up with them day after day. However, here are a few examples:

- Nearest phone does not work properly (more common than you might think)

- Basic tools needed to do the job are missing

- Light bulbs are not working

- Leaking valves

- Clutter

- Hard to operate taps/valves etc

- Inappropriately sized boxes or bins for holding materials

- Points where product jams frequently

- Point where product can fall off the line

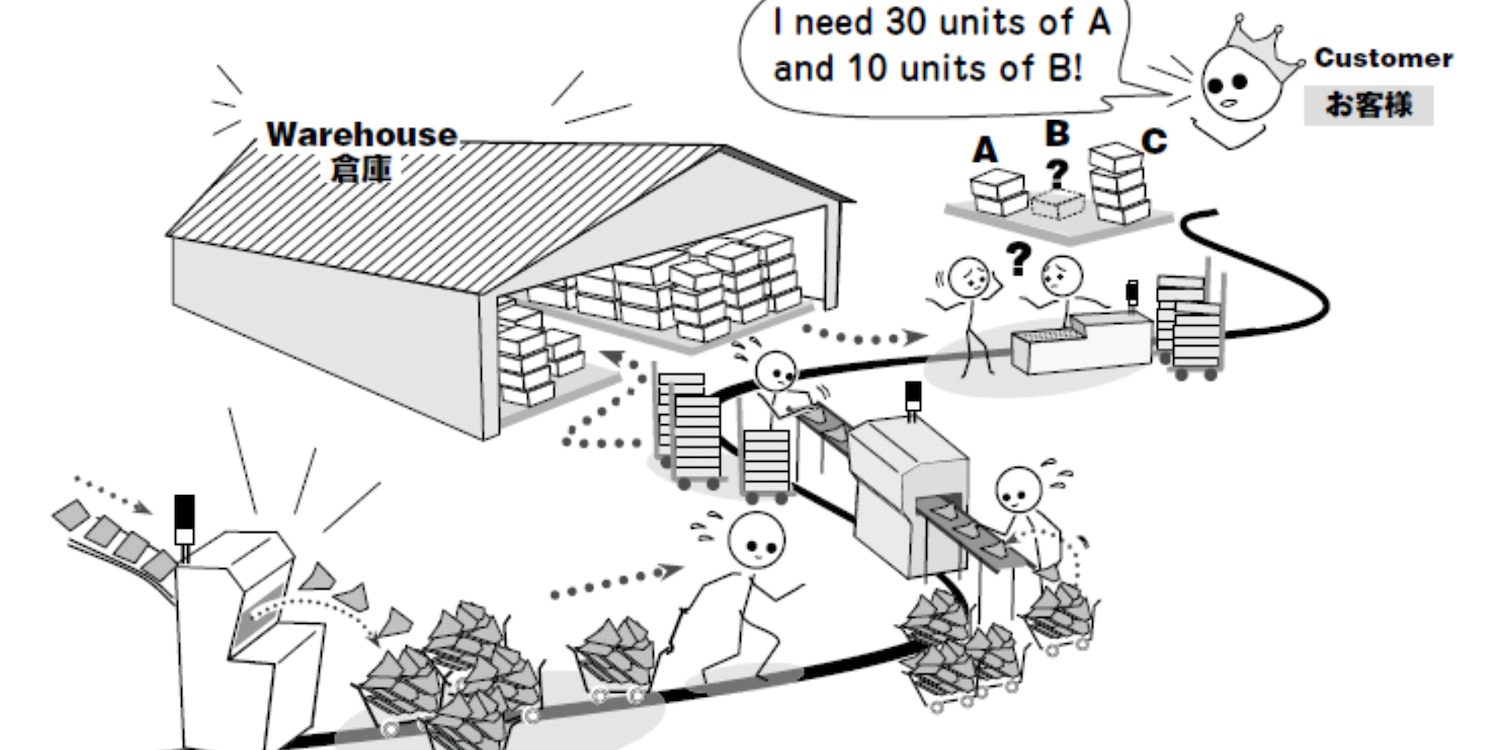

- Having to walk some distance repeatedly to get materials

The list of niggles goes on and on. A favorite example of mine is from a global food manufacturer where I ran several five-day workshops for the rapid implementation of levelled production. During the niggle-finding exercise, the same annoyance came up in every factory: in food production people are not allowed to wear jewelry or watches on the shop floor, but all the clocks in the factory were showing a different time. It was common for operators to say to me: "Management keep telling us we should all follow the same work standards in running equipment, yet they can't even get the bloody clocks right!"

NIGGLES AND THE CONSULTANT SURGEON

We recently ran another one of these workshops at a surgical hospital in the UK, with a number of consultant surgeons attending. When the team members were selected, it was decided to put one surgeon in each team. There was – as always – a niggles team. The surgeon in this team was wearing an expensive suit and had a rather aloof (or arrogant) attitude. His response to being put in the niggles teams was: "You are not seriously suggesting that I, a consultant surgeon, spend my valuable time finding what niggles exist in this hospital?" He was told that was exactly what was expected of him.

On Monday afternoon, the niggles team designed their check sheets, went around the hospital explaining what they were and what people needed to do. The team decided to leave the sheets up overnight and to come in early Tuesday morning to go and see what crosses there were. They then asked people about their niggles before having them report back to the rest of the workshop participants on what they had found.

To everyone's surprise, it was the consultant surgeon who gave the report back. He truly spoke from his heart when he said to the rest of the people, "I had no idea the sort of things people in this hospital are having to put up with. It is outrageous we allow these things to continue. No wonder motivation is so low! I thought it was due to government interference and target setting. It's not – though that may play a part. It is down to us, the senior people in the hospital – we are not recognizing what nurses, porters and ancillary staff are dealing with every day. I personally intend to fix as many niggles as I can this week." He then left the hospital but soon returned wearing trainers, jeans and a T-shirt and carrying a toolbox. He was good to his word: he and the rest of the niggles team worked long hours that week, encouraging people to help them get what they needed to fix the niggles. By the end of the week, 123 niggles out of a list of 168 has been fixed – 73%. The difference in the surgeon's approach and in the way people were interacting with him could not have been more different from what we had witnessed on the Monday morning.

Some time after the workshop I received a call from the head of nursing at the hospital. She told me the atmosphere had completely changed: people were being nicer to each other, helping each other out more and smiling more. She said the week had changed the culture – and "fixing the niggles" was what everyone remembered about the week.

Fixing the little things – niggles – matters. It says something about your culture, attitude and approach to improving what you do. Just as not fixing them does!

This article is also available in Polish here

THE AUTHOR

Ian Glenday is a lean coach and sensei with experience supporting change in several industries, including chemicals, food and drink, and pharmaceuticals. He started his lean journey in the late 1970s as a micro-biologist running a fermentation plant producing enzymes, where he first began developing Lean/RFS concepts and principles for application in process industries. He later joined Reckitt & Colman, later becoming Head of Policy Deployment based in Norwich, England where substantial increases in sales per employee, market share and profit margins were achieved by applying lean across the whole company. Ian is also author of two Shingo award winning books: Lean/RFS: putting the pieces together.

Read more

INTERVIEW – The CEO of a Scottish health board takes us through the organization’s long lean journey, reminding us that allowing people to take the initiative often leads to the most impressive discoveries.

FEATURE – What if we ran our production schedule to time instead of quantity? While creating overproduction, running to time is a temporary first step to establish levelled production with fixed repetitive cycles.

FEATURE – After Singapore Institute of Technology staff was introduced to lean thinking, a course was launched to provide healthcare workers with the lean skills they need to transform their organizations.

FEATURE – The release of Christoph Roser’s new book All About Pull inspires John Shook to discuss the origins and true meaning of “pull” and why it is incorrect to blame JIT for the shortcomings of global supply chains.