Approaching problem solving more effectively

FEATURE – As they progress on their lean journey, organizations need to learn to adjust their stance to the different types of problems they face. Introducing his new book, the author offers precious tips on problem solving.

Words: Art Smalley, President of Art of Lean, author and speaker

Last year, the Lean Enterprise Institute published a book I authored, entitled Four Types of Problems. The book emphasizes the importance of looking at problems from different angles and not always getting locked into one way of viewing the situation at hand.

The four types described are 1) good troubleshooting routines, 2) gap from standard deviation situations, 3) target state improvement opportunities, and 4) more open-ended or innovation-based routines. There is some overlap between adjacent types, of course, but each has its own purpose and methods associated with it.

My goal in writing the book was to explain how these four types function in a company like Toyota, where I previously worked, and help organizations navigate their own problem-solving journey more effectively.

The book has a short chapter on the history of problem solving in the 20th century and covers many of the influential parties. As I point out in the chapter, I think it is fair to claim that all problem-solving routines are loose derivatives of the scientific method of inquiry in concept. However, I don’t think that all problem-solving routines meet the requirements of actual science in practice. (As an aside, I worked with a national laboratory for many years on their improvement journey. As I was lectured many times by career scientists, the actual bar for the scientific method is quite high – e.g. conduct double-blind studies, publish your full data sets and investigation methods, subject yourself to peer review, have others replicate your results independently, publish in a journal, and establish some type of new knowledge or discovery in the process, etc. OK, we don’t go that far in problem solving but we loosely embody some of the elements.)

The first two categories in the 4 Types framework involve higher degrees of critical analytical thinking and look for proverbial root causes. They tend to reactively deal with problems that have occurred due to some type of causal factor or error. The latter two types are proactively created and not necessarily caused. In other words, you choose to take something to a higher standard. This usually involves higher degrees of lateral or divergent style creative thinking methods and you look for better solutions even when there is no problem per se.

There is a Japanese proverb that essentially states, “a fool knows one way of doing things while an expert knows many.” In other words, it is easy to force all problem-solving routines into one specific box – whether it be Toyota’s current 8-step method, Six Sigma methodologies, Triz, 8D, Kepner Tregoe, rapid Kaizen, Design Thinking, or whatever flavor you are most comfortable with. And we can, of course, just become extremely abstract or non-prescriptive and say it is all loosely science or PDCA for that matter. However, that superficial approach does not really provide much in the way of practical advice for moving forward. And unfortunately, I see many organizations get stuck with this line of thinking and consequently struggle to achieve the desired results. If you are experiencing success in your organization then I suggest you stay with what is working. If your organization is experiencing some trouble with problem solving or improvement, then altering your viewpoint or framework might be of some use.

I often get asked this follow-up question: “Why do you recommend these specific four types and why are they all necessary?” Let me try to explain my thinking. First off, these four types are essentially the patterns I personally observed from my mentors while working inside of Toyota Japan at Kamigo Engine plant (Taiichi Ohno’s facility). These four types line up with my observations and experiences watching various experts over many years at work during their career. Also, a retired gentleman named Isao Kato, who was a major force in the development of problem-solving training at Toyota for decades, urged me to look at every problem from multiple angles and not just one. He often invoked the phrase “Kata ni hamaranai” – a common Japanese expression that translates into “not getting trapped into one way or method”. Subsequently, here is the way I attempt to describe the types and necessities.

THE FOUR TYPES, MORE IN DETAIL

In a perfect world, we would not need Type 1 Troubleshooting routines… but the world is not perfect. Resources are finite and very much constrained in the short term. During a major vehicle launch in Toyota, for example, data collection indicates that the andon chord is pulled signaling an abnormal condition up to 10,000 times in a 24-hour period. Anyone remember those Elon Musk tweets about “production hell” and “logistics hell” while Tesla attempted to ramp up production volumes? Minor problems abound and not all of them are equal. Some form of triage is essentially enacted, with the most critical getting the most attention and others getting lesser amounts of consideration. Some are pursued more deeply in terms of 5 Why thinking (ideally again all of them would be), but many are dealt with in a safe expedient manner to get production back on track. For example, the machine is unjammed, the error is reset, the software is re-booted, the alignment of something is re-centered, etc. etc. How many of you have ever turned your internet router or phone on or off to resolve some type of connectivity issue? Sometimes the short-term fix is allowable under the circumstances.

There is a tendency to put down what I term the Type 1 Troubleshoot routines as not real problem solving, but I think this is ill advised for many reasons. For starters, it is not always so easy to be a first responder in any organization. Most of my trips to ER, for example, ended in pain medication, antibiotics, or other reactive treatments. One can argue those are just troubleshooting techniques dealing with the symptoms and not the real underlying problem. An entire movie starring Tom Hanks was made about Apollo 13 and the famous phrase, “Houston we have a problem”, when an oxygen tank ruptured during a mission. However, the movie then depicted the heroic troubleshooting required to get home, overcoming equipment malfunctions, CO2 build-up, low temperatures, lack of food and potable water, and many manual course adjustments. The real problem of the tank rupture and root cause (incorrect heater thermostatic switch) was figured out much later and not really covered in the movie. My point is that sometimes circumstances force you into Type 1 Troubleshooting responses and you need to be good at it on a daily basis. Also, from a “respect for people” point of view, involving everyone right away in Type 1 routines is a vital concept in Toyota. Most organizations I visit are not as strong at Type 1 problem solving as they seem to believe.

Type 2 problems and the classic gap from standard pattern of problem solving exist because of the inherent limitations of Type 1 responses. All problems are not equal in terms of impact – i.e. there is always some type of Pareto distribution. Of course, sometimes a problem must be handled at a more fundamental level even if it affects safety or quality severely. Many of the techniques developed in the 20th century focus on this type of situation. In order to really fix something you have to understand the proverbial root cause and implement a countermeasure to prevent it from occurring again. Penicillin and pain medication, for example, are great… but what caused the infection in the first place? Why did the Apollo 13 oxygen tank malfunction and rupture? Why are we suddenly experiencing so many defects in the fabrication department? These problems require more diligent investigation. The thinking pattern must shift from addressing the emergency condition to the underlying causal factors involved.

Most organizations struggle with Type 2 problem-solving routines as they are usually more difficult. Problem solving requires skill and teamwork as well as proper support structures. Heroic individuals usually can’t resolve Type 2 problems by themselves as the causal factors cross multiple lines or require certain expertise. We flew an induction hardening and materials expert all the way from Toyota Japan to the United States once during start up, to deal with a specific problem on a piece of equipment that my staff and I could not resolve. Most Type 2 problems, however, can be solved internally by proper usage of tools, methods, and persistence. Some fall into what I call the logic family of analysis (5 Why or Fishbone), some into the one variable at a time (OVAT) statistical family, and some in the multiple variable at a time (MVAT) statistical category. Not everyone needs to be proficient in all of these techniques, but all organizations need some degree of ability in them.

Type 3 routines are critical and different from the previous two types as there is not necessarily a problem to address in a classic sense. Everything is stable and at standard, which is great! Annually, however, organizations set higher goals for internal improvement or out of concern for the competition. Customers expect improvement as well. Sports is a good analogy here. Whatever you ran the 100 meters in or pole-vaulted last year is fine. How much better are you going to be this next year? Game on.

These types of problems are what we historically called Kaizen or continuous improvement inside of Toyota. The bar is raised and a new standard of performance (safety, quality, delivery, productivity, cost, etc.) is targeted. In these cases, traditional convergent root cause thinking is not as useful since the answer is not in the past or a single root cause per se. The 20th century also flourished with creativity-based routines to come up with a better combination of existing resources to optimize the current state. Creative brainstorm is the classic example where judgement is intentionally suspended, a quantity of ideas is targeted, and set of better methods is identified for one example. This line of thinking is intentionally exploratory and requires a higher tolerance for trial and error for the purposes of learning, etc. I semi-jokingly use the phrase “wishbone” instead of cause-and-effect “fishbone” to accentuate the difference.

Type 4 routines might require the least amount of explanation, but generate the most amount of debate. Open-ended innovation is needed in the first place to create an industry and some type of new product or new service. In the grand scheme of things, without Type 4 problems society does not grow or develop new technologies, etc. There are many areas for open-ended thinking and opportunities for improvement, but very little agreement on how to produce it. Most Type 4 practitioners consider it to be a special category in itself. Noted innovation expert Matthew May, upon kindly reviewing early drafts of my book, for example, commented there was “innovation” and then “just everything else”. Most innovation experts cringe at the notion that dogmatically adhering to specific steps or just answering questions will result in a specific outcome. Creativity is often messy and iterative in nature and not always sequential. Paradoxically, while it employs science, it is not all that scientific itself in terms of practice. In other words, similar methods don’t always produce the same results, which is one of the hallmarks attributes of science. This is partly why I suspect societies are so enamored of eccentric artists and inventors like Da Vinci, Edison, Tesla, or more recently Steve Jobs or Elon Musk.

If this sort of thinking interests you or your organization is not achieving desired results in problem solving, then this book might be of value. It is perfectly fine in the beginning to cling to one way of doing things and have a standard, for example. I can play golf quite well with just one swing and a 7 iron or play a decent game of tennis with just a forehand volley. Advanced players, however, employ multiple techniques depending upon the situation. Without first-hand observation or factual data, I don’t like to make specific recommendations. You have to be the captain of your own ship, so to speak, and plot your own course and periodically adjust. I personally believe that Toyota is successful because it is flexible enough to recognize various problems and respond to them in a multitude of appropriate ways over time. As Isao Kato frequently cautioned to me, “Kata ni hamaranai”.

To purchase your copy of the book, click here.

THE AUTHOR

Read more

THE TOOLS CORNER – This month, the author discusses how we can ensure quality problems are identified early, tackled swiftly and prevented from reoccurring.

FEATURE – In May, the author told us how the IT department at Fuji Xerox Australia used book clubs to engage people in lean. In this update, he explains how the efforts were brought over to a different area of the business.

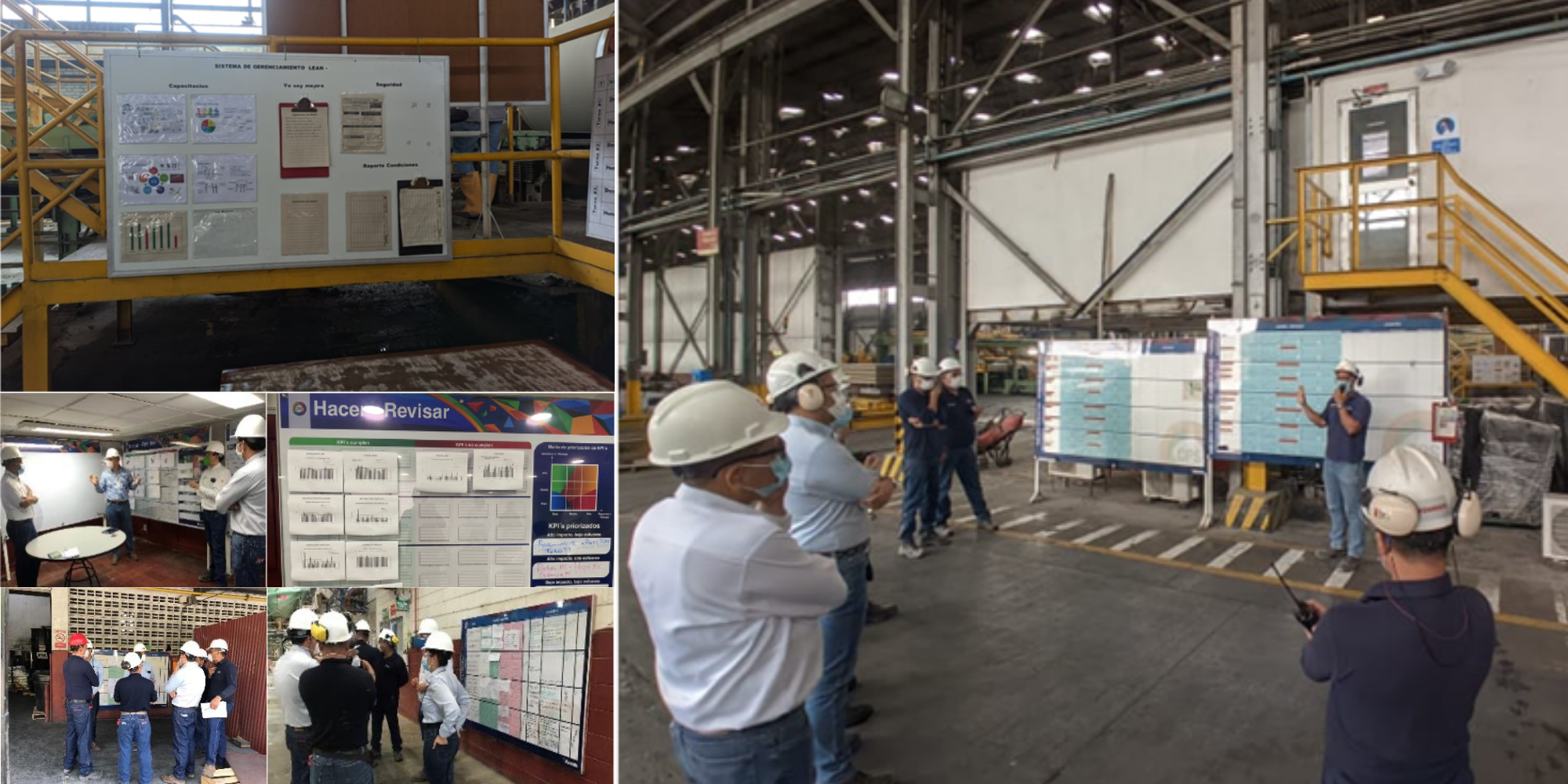

CASE STUDY – For the past year, Elementia Materiales, a producer of materials for the construction industry, has begun a lean journey that’s already brought impressive quality results.

FEATURE – Technology should help people in their work, and it is with this in mind that the general manager of this car preparation center decided to learn to develop Apps.