Inventory reduction and pulled supply in a Brazilian factory

FEATURE – Inventory reduction is critical to waste elimination. Yet, many are reluctant to do it, fearing demand variability and production instability will neutralize their efforts. Grupo Sabó's story proves otherwise.

Words: Ricardo Avila, Industrial Director at Grupo Sabó; Douglas Agassi, PCP Coordinator at Grupo Sabó; and Alexandre Cardoso, Project Manager at Lean Institute Brasil.

When the economic crisis first hit Brazil in 2015, the director of Grupo Sabó – a multinational organization that provides sealing and fluid routing systems for the automotive industry – realized that, despite the excellent results the company had achieved over the years by using lean thinking, there was an opportunity for further improvement: drastically reducing inventories across the business.

With this in mind, the company launched a global project that aimed to reduce inventories of all units by 50%, without compromising delivery. The project was led by one of us (Industrial Director Ricardo Avila), with the support of Ivanaldo Maciel da Silva, the Supply Coordinator.

Ivanaldo prepared an A3 to address this challenge. Having identified the financial potential of the project, this initial A3 was used to create other A3s specifically focused on each Grupo Sabó plant. One of them, a sealant factory located in the city of Mogi Mirim and working with the national market, exports, and After Marketing, had a stock level of around R$8 million [Reais, the Brazilian currency] in inputs and finished products.

The Mogi Mirim factory has been implementing lean since 2007, when it embarked on a journey in search of productivity gains. Over the years, the plant achieved great results: stability in production, an improved flow of materials, and a boost in productivity. Now, for the first time, they found themselves having to reduce their inventory – by a staggering R$4 million.

The first step they took was working hard with Sabó’s suppliers to convert the company’s inventory management system from push to pull. The new project was spearheaded by Ivanaldo and by another one of us (Production Planning Control Coordinator Douglas Augusto Agassi), with the participation of a multifunctional team and the active support of leadership. It began in March 2016.

GEMBA WALKS IMPRESSIONS

The team at the Mogi Mirim factory began by walking the gemba. It is a common mistake among lean practitioners to think that the gemba is a fixed location; it is, instead, where the actual work takes place and it, therefore, varies depending on the work you are observing and aim to change. In this particular instance, the objective was reducing inventories and the gemba was the logistics value stream in its entirety.

After two days walking up and down the value stream, the team learned three critical facts:

- Sabó’s logistical planning was based on push rather than pull, which created inventories at different stages in the process;

- Inventory levels were much higher than demand, and had become an obstacle for employees.

- There was a lot of material in excess by the machines. These were often delivered long before they were actually used.

A simple walk along the logistics value stream revealed opportunities for improvement that could not have been discovered by running a project from an office. The team was convinced that reducing inventories and introducing a pull system would bring significant results in both the short and the long term.

Such is the power of a gemba walk: it opens the eyes of a manager to the reality the employees experience every day. It is, however, only one aspect of a successful lean transformation: the team knew of the difficulties with inventory control and quickly realized the next step towards better understanding the problem would be value stream mapping.

FROM CURRENT TO FUTURE STATE

When mapping the value stream, we must define two things: the current state (how things are today) and the future/ideal state (where the business wants to go). In drawing the map of the current state, the Sabó team had an important revelation: the largest inventories in the company were represented by raw material (the basic frame of the sealing systems, its structure). In some cases, there would be enough stock to supply the company for 62 days, while other necessary items were not available. What was even more curious was that keeping such a high quantity of inventory was completely unnecessary, since the supplier was based a short distance away from the plant (approximately a three-hour drive).

Despite the proximity of the supplier and excess inventory that did not correspond to demand, the team was facing a problem that typically occurs when one is about to reduce inventories: fear. After all, not having raw material available for production is pretty much a manager’s worst nightmare. How, then, to reduce inventory without damaging the product, compromising deliveries and frustrating customers? The answer, it turned out, can be summarized in three words: inventory turnover ratio.

With all the information from the current state map in hand, the team moved on to apply lean principles and practices to the process – and therefore, to imagine and work towards their future state. The goal was to reduce the inventory by 50% and the team estimated that reaching it would mean increasing inventory turnovers from seven to fifteen a year.

With the goal clear in mind, the team further analyzed the problem at hand to try and identify, and then tackle its root causes. The team at Mogi Mirim identified a number of extra causes (in addition to the ones they had already found, raw material flow and inventory levels): a MRP software generating high inventories (it pushed instead of pulling); planning done with no financial vision; and little flexibility and long lead-time in the manufacturing process. Now countermeasures could be devised.

THE LEAN LEAP

It was time for the Mogi Mirim team to make the leap from the current state to the future state. Using the A3 executive report, signed off by the entire team and by the company’s president, José Eduardo Sabó, the team started listing possible countermeasures, established a plan of action, and began implementation.

Three countermeasures were identified:

- Implementing supply routes

One of the main actions we took to reduce inventories was the creation of a new supply system for the lines. This was an attempt to respond to the excess materials by the machines, something that could be seen as unavoidable due to the fact that there was only one delivery of material per shift. So, instead of making big deliveries a few times a day, the team looked to have more frequent deliveries in smaller quantities: they started to supply materials every hour. With this measure, the amount of material next to the machine was reduced by 75%, and 90% less items returned to the warehouse at the end of the day. Using a kanban system, the operator could now request only what he would use in the next hour, without having to physically go to the warehouse. This supply route strategy brought stability, eliminated rework and prevented perishable materials (such as the rubber used for sealing) from expiring. Standardized works was also introduced for the operator of the supply route, to ensure material was ordered at the right time and in the right quantity.

- Implementing a pull system with the main suppliers of product frame

This was a great challenge, because implementing a pull system can cause unwanted reactions from suppliers. They often don’t understand the new process, as they are used to receiving monthly orders and delivering in large batches. Sabó’s Mogi Mirim factory was able to implement a pull system that helped the logistics department to create a supermarket of parts with just a few kanban cards.

Initially, inventory was reduced from forty days to five: deliveries drastically decreased in size, which caused a crisis at the supplier. The Sabó team knew that if they wanted the project to go ahead, they’d need the supplier on board. So, they went to see the supplier and helped them to adapt to the new process. It took some time and a lot of effort to coach the supplier’s employees, but eventually the two teams managed to get aligned.

Once they mastered the use of the pull system, the team started to apply the same idea to other important parts of the business, reducing stock in each of them: before too long, all materials were stored in a single place that was much smaller than the previous ones.

- Establishing a heijunka box in the production schedule

After improving the levels of raw material inventory, the team felt the need to synchronize the work of the different areas in the company and, therefore, improve production scheduling (it took the PCP people a long time to program the machines – up to five hours at times). When the team heard about a tool called the heijunka box (also known as leveling box, used to level the mix and production volume and to distribute kanbans at fixed intervals), they immediately decided to run a pilot. As a result, the machine programming time dropped to just 40 minutes, which was a relief to the PCP area, who could now spend time on other important planning activities.

In addition to this tool, the PCP area started using visual management: logistic protocols with the supplier (establishing the systematic planning and material pull), standardization of the number of pieces per package, and standardized work for kanban and heijunka box.

WHAT WE LEARNED

Sabó's Mogi Mirim factory has reached all the goals set at the beginning of the project, but we are very much aware that the lean work never ends. Our breakthroughs seem to indicate a positive trend towards ever more ambitious goals in the future.

Here’s some of the results we have achieved through the project:

- The annual inventory turnover was 7.51 at the beginning of the project. After a year, that number rose to 13.69. In January this year, the company reached 15.64, surpassing the goal of 15.08.

- Within one year, the reduction of inventories of the Mogi Mirim plant reached just under R$3 million. Currently, the reduction is R$82,000 past the R$4 million goal (at R$ 4,082,000).

- By December 2016, purchases had been reduced by R$ 3,138,468, exceeding the established goal.

- The lean work across all Sabó operations in Brazil – the scope of the first A3 – led to a reduction of 61% of the capital employed in inventories, compared to the goal of 50%, while raising more than R$35 million for the company. The project enabled Sabó to achieve superior results using less capital, which is of great help in a time of crisis.

We learned a lot over the course of this project, with the three main takeaways for us being: don’t have high inventory levels, but high turnover; supply should be continuous and pulled, not pushed; let customers pull rather than push based on your forecast.

As our inventory reduction efforts continue at full speed, the team at Mogi Mirim is already thinking about the next challenge. Grupo Sabó now wants to deepen its understanding of lean thinking across its South American operations, while working more on the manufacturing side of the business and exploring the use of lean in other areas, such as product development or the office. We will let you know how it goes.

THE AUTHORS

Read more

CASE STUDY – A physician tells PL the story of how the East Denver Medical Office became a catalyst for the lean transformation at Colorado Permanente Medical Group.

ARTICLE – The Institut de Medicina Legal de Catalunya has learned that employee engagement and lean thinking can shake up even the stiffest of the public sector's working environments.

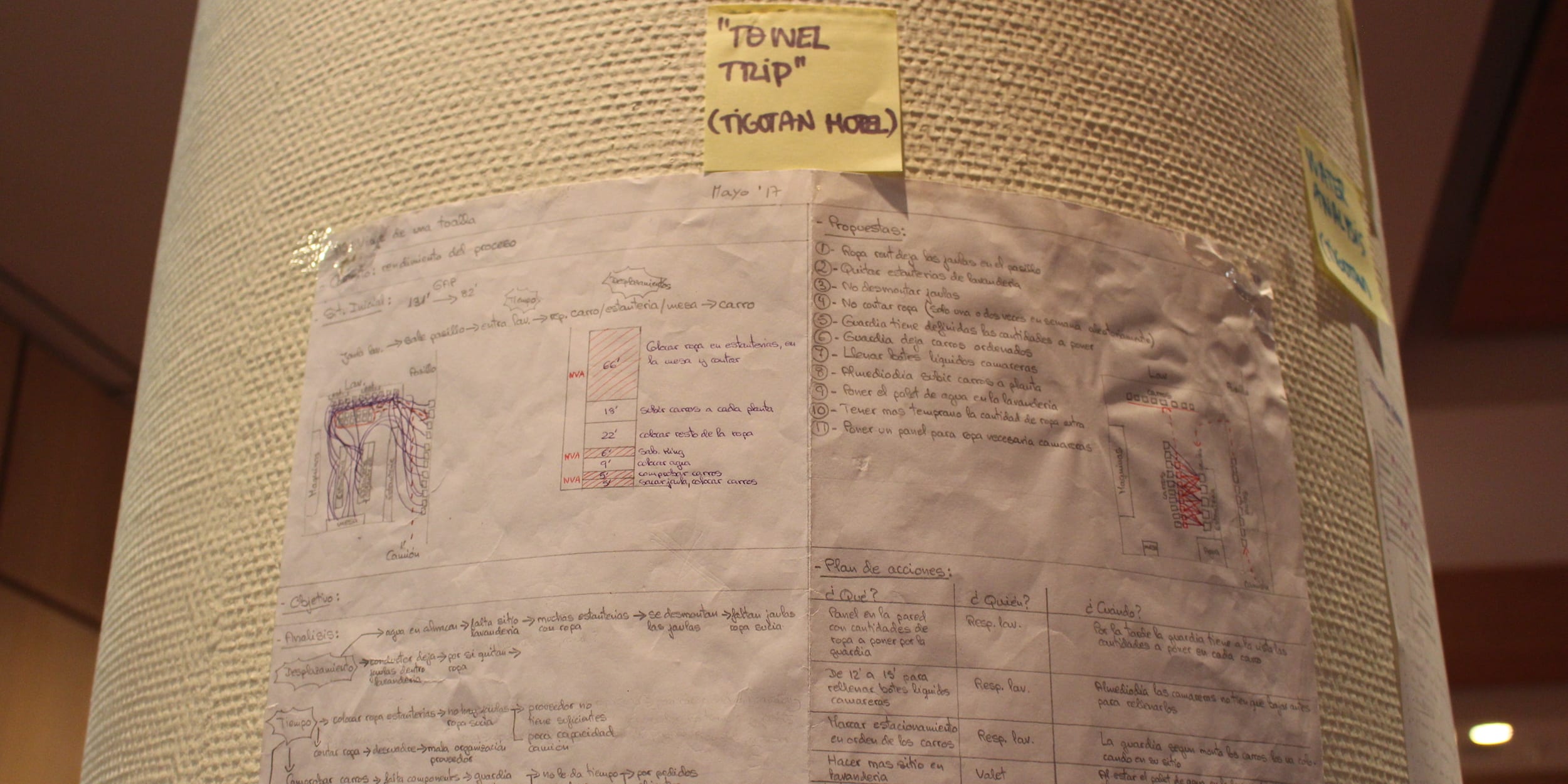

VIDEO – The director of a hotel in Tenerife explains the first steps the team is taking to develop a lean daily management system, and how this connects to the organization's hoshin.

FEATURE – During a recent Jishuken workshop, Poland-based Schumacher Packaging experimented with a newly-developed App to quickly create standardized work instructions at the gemba.