Learning at takt time in Thales

INTERVIEW – A former VP of Operations from Thales tells Catherine Chabiron how he and his team turned around their department by committing to lean thinking and focusing on people development every day.

Interviewee: Norbert Dubost, former Thales VP Operations

Interviewer: Catherine Chabiron, lean coach and Board member of Institut Lean France

Catherine Chabiron: As VP Operations in the Microwaves & Imaging Sub-systems Division of Thales, you and your teams achieved some incredible results over the last two and a half years – a 50% reduction in late deliveries, a 50% reduction in customer returns, a 30% increase in cash, a 20% increase in productivity, 30% less scrap and reworks, 50% less work injuries, a 20% drop in absenteeism, and the number of improvement ideas by year was multiplied by 10. How did you achieve this?

Norbert Dubost: Lean management is designed to work seriously, deeply and with method. I would say it is a machine to transform industry and make it successful. Lean is a long-term commitment and I believe the role of the executive is to transform his or her company in a sustainable way.

Yet, if you asked my former bosses and shareholders, they would not be so enthusiastic because the non-quality costs we could measure only showed a 20% reduction versus the 40% I promised. I have always been too optimistic when playing cards, that’s my weakness. I was probably too confident when I took over the position, but I thought I could use this last step in my career before retirement to show what lean could do in as dire a situation as MIS was in. I wanted to show them what lean had taught me and how I could help them achieve a complete transformation or recovery. Come to think of it, I wanted to prove it to myself.

CC: If you had to start over again, what would you do differently?

ND: In large corporations like Thales, operational communication is in the hands of Finance. If you can’t convince the CFO, you are doomed because he or she is the communication channel that is listened to as far as results are concerned. Corporate won’t fully hear you when you improve industrial KPIs, because they prefer to keep their eyes on the bottom line. They might be convinced to check the non-quality costs. So, if I had to do it again, I would pay much more attention to two things:

- Use their language to prove my point (for example a combination of my lean strategy hoshin and the roadmaps they use to plan ahead).

- Spend more time with the CFO, link everything I do to something he can relate to (like non-quality costs), and negotiate more realistic interim P&L results.

A CFO’s thinking and budgeting is built on the Bill of Materials routings and data entered in the system by technicians from the Methods Department. They use it to calculate what the results should be, but routings in the systems are far from real life: I have seen routings in SAP with operations lasting two weeks! How accurate can that be? In the end, they build standard costing and consequently budget on sand.

CC: Can you give us a real-life example of a routing?

ND: On any given routing, what you will find is something like this: one operator will do it in 10 minutes, another in 100 minutes, the average of the team will be 70 minutes. Our real challenge is not to explain gaps versus budget, but to bring down everyone to 10 minutes.

CC: Are you saying there were no standards for this in the Microwaves & Imaging Sub-systems Division?

ND: Very few indeed! The size of our stock was directly related to the absence of standards. When you have no repeatability, you cover up with inventory.

By the way, when you are educated, hired and developed into a manager, you are totally unprepared to see the importance of standards and yamazumi. Routings in SAP are at best a sequence of operations but they are far from the minute details we need to go into to define the best gesture in time and quality.

Nobody is interested in standards. The disconnect between operators and management is huge. They are in two parallel worlds that never meet in our big corporations. One of my predecessors had simply stopped going to the gemba. And my middle managers were afraid to go, like a tourist arriving in a developing country who is afraid to leave the beach resort to go see the slums.

Conversely, Toyota works on the capillarity of the two worlds, using “fertilizers” – such problem solving or quality circles – to grow ideas and nurturing both worlds with kaizen. Thanks to the lean approach, as you can guess from the operational results you mentioned, we did put MIS back on track.

CC: How did you manage the lean transformation in MIS?

ND: I started by introducing pride in the work. We implemented Jidoka (we call it Stop-and-Fix) and introduced takt time in minutes when everything before was counted in days or weeks – if not months. When on the gemba, I was at times tempted to select different elements to focus on – for example, trying suggestions but leaving pulled flows aside for a bit. But real lean calls for the complete application of TPS principles: Just-in-Time, Jidoka, standards, kaizen, mutual trust, employee satisfaction, and of course an ever-lasting focus on the customer.

One must not underestimate the technicity of lean. To fully understand and develop lean techniques takes longer than one thinks (think of pulled flows, or problem solving). I see this like an orchestra playing music, a sophisticated technical language that requires people to work together, so that they hit the note at the same time without looking at each other.

And just like in an orchestra, you must invest time and training to: 1) learn to play your own instrument (deepen the understanding of your job with kaizen and standards); 2) read the music (learn to recognize the signals for action and timely send your own signals); 3) practice as a team to play to the beat (learn to react to anomalies, practice teamwork, keep to the takt).

Lean is sophisticated, and you have to work hard to succeed at it. Luckily, you can derive a great intellectual and scientific pleasure from it.

CC: Can you tell us more about this notion of time, beat, and takt?

ND: When you introduce takt time and Kanban, you change the overall beat of your plant. With Kanban cards piling up on your launcher, your time becomes that of the Takt. In Thales MIS, the takt is still around one hour on average (which is very far from the automotive standard of roughly one minute – as in, one car produced every minute). But to see a new Kanban card added to your launcher every hour leaves little time to deal with reworks and anomalies.

One of our biggest issues in MIS was that, as we had left the operators alone on the shop floor and failed to properly train new ones, the quality of the right-first-time assembly varied immensely. In some instances, 70% of the product actual cost was scrap, rework of parts and gestures at work stations, waiting time, lack of training and, generally speaking, non-quality costs.

Now that we had the tension provided by takt time, we could implement Stop-and-Fix, which was not exactly stop at each anomaly, but stop at first doubt (we practically had no clear standards). Fix did not mean we had found the root cause to resume production, which was impossible if we wanted to stick to takt. What it meant is that we had determined the best conditions to resume production. Containment measures, small kaizens at the workstation and improvement ideas can be managed within the team and the takt time frame, but we had to find other ways to deal with major or transversal issues. This is when we started with Fix Experts and A3s, to try and improve the problem solving (which caused me quite a number of hot discussions with my sensei as he pushed for Quality Control circles with people in operations, and was wary of the development of experts in problem solving). Still learning, as you can see.

CC: What did lean teach you?

ND: I am passionate about visual management at the gemba. I like asking lots of questions about things I don’t understand, and spotting anomalies to start working on them with the teams. I am amazed by the total disregard some people have for visual management. “Why do you want me to implement clear signals? I don’t want to offend them by explaining in detail the next task they have to perform”. What they don’t see is that clear signals take a mental load off operators, making their jobs easier and more fluid.

My big revolution was to start going to the gemba very regularly (every Tuesday, for a full day). When I came out of a gemba session, I felt both elated – “Great, we learned plenty” – and frustrated – “We see the problems, but how to handle them?”. What I learned is that a transformation is fastest at the gemba. I am fascinated by the operators’ ability to engage: Thales operators have been there for 30 years holding the fort and are proud of their products (and sad to see the waste around it). They never let go. Kaizen and kanban signals talk to them, but so do muda and mura. People on the floor in MIS have really reacted well to lean.

Another important thing I did was to apply lean to my own activities as Operations VP. How can you entice people to think lean if you don’t live it every day yourself? I started changing my relationship with time, which up until then had been defined by project planning, milestones, long meetings, days, weeks, months. I started introducing shorter time deadlines in my day, put a clock in my office, and reduced the length of the meetings to a maximum of 30 minutes.

I also maintained an Obeya in my office that managed KPIs, of course, but also transformation projects led by my staff, Stop-and-Fix alerts that could not be solved in time in Operations and were escalated to me, major customer issues, things to learn (deep dives), and TPS tools under construction.

One critical thing I learned on the gemba is that no sustainable progress can be achieved without detailed attention to people development. Take the example of the Thales MIS site of Thonon Les Bains. They worked hard on the subject and found that the mastery of 250 different technical processes was needed to build our products right-first-time. And those processes needed to be taught and rehearsed again and again, like in sport, because some of our products are not manufactured at a high frequency. What they are looking at now is pulling the training need based on the next products to produce, instead of pushing a massive deployment of training that is hard to manage and will become obsolete within days if the gesture is not required immediately.

By the way, we created an internal school in MIS, called the “Tube Academy” (this is what MIS makes, electron tubes and transmitters at the heart of many of today’s high-tech systems. When you connect to the Internet via satellites, wherever you are in the world, nine times out of ten you do so through a Thales tube). We need such internal schools in each site.

CC: Why do we underestimate this need for people development?

ND: We, at top management levels, generally make two wrong assumptions:

- Industry is a complex subject. To survive, we fail to understand that specific techniques and detailed know-how are just as hard to acquire and retain as it is for a top-performing sports team.

- In large corporations, we believe we have recruited the best people, with the best know-how, but that is wrong. We all need to continue learning, all the time.

CC: What would be your recommendation to other top managers?

ND: I am frustrated to have discovered lean so late in my career, so do not delay investigation and learning on the subject. I truly started to understand lean in 2010 and have been a convinced advocate of the approach ever since.

Another thing I learned and would like to pass on is this: you can actually count on your teams, if only you take the time to explain. Trust them, and they will repay you ten-fold. But no lean transformation will work unless you lead it yourself. That’s the role of an executive.

As you start, don’t underestimate the importance of the guidance and support a sensei can provide you with. Mine gave me a completely new sense of what my job was.

THE INTERVIEWEE

THE INTERVIEWER

Read more

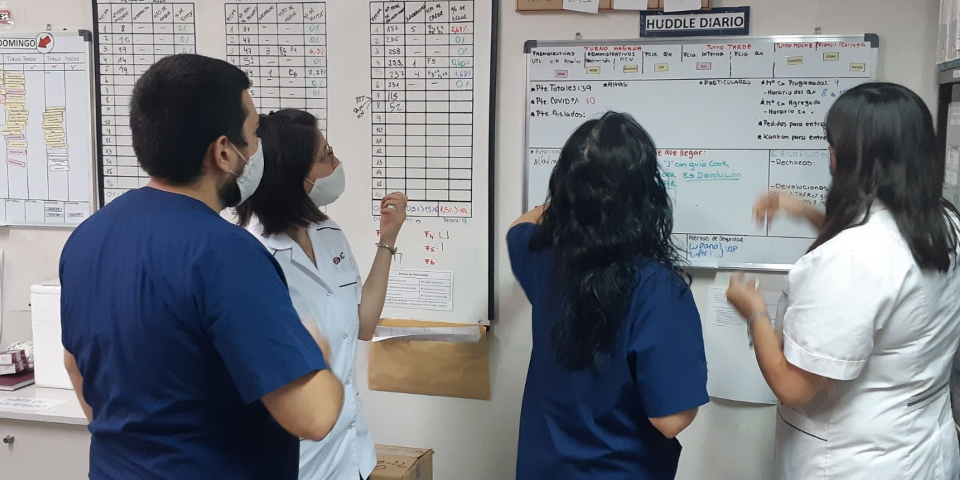

CASE STUDY – This hospital in Argentina has leveraged the power of Lean Thinking to greatly enhance patient care, even in the pandemic, and receive internationally renowned accreditations.

FEATURE – The goal of your digital transformation is not only to develop new technologies and innovative processes, but to turn your people into the kind of "smart creatives" who will lead your firm into the future. Lean will get you there.

COLUMN – Creating a learning environment that welcomes problems and experimentation and adapts to market changes should be our main objective. So why do we stick to obsolete ways to teach and develop people?

FEATURE - Can a company be considered lean if its improvement efforts result in layoffs? The author answers this frequently asked question drawing from his own experience dealing with organizations.