Tracey Richardson on the deep meaning of standards at Toyota

FEATURE – Through this intimate anecdote from her days at Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, the author tells us of her experience with standardization… and of the deep leadership lessons hiding behind it.

Words: Tracey Richardson, lean coach, author and President of Teaching Lean Inc.

During my time at Toyota, I have learned that while performing as individuals was important, it was working and improving together as a team that really mattered in the organization.

It was amazing to me to experience a different culture first-hand, and at such a young age, through interaction on the job and at the gemba with trainers. I was living and absorbing the values of continuous improvement, teamwork and respect through my daily work, and didn’t even know it – it was a conditioning process.

My first trainer on the Plastics Instrument panel line, Takahashi-san, wanted to make sure we understood “what” we needed to do, but his real mission was for us to also understand “why” we were doing it. This understanding can sometimes mean the difference between a complacent team member and one that is engaged and empowered.

Sometimes, particularly early on, we made mistakes in our standardized work, especially around sequencing the instrument panels to Assembly. On those occasions, Takahashi-san would take the time to show us why it was important that we followed the specific steps in their proper order. If people weren’t following the sequence, you would get many versions of how the work was completed, which in turn could lead to defects or wrong parts or colors and make it very difficult to track down abnormalities.

I truly believed the leaders felt setting a standard without the proper discipline behind it was like having no standard at all, and that this would have a harmful effect on culture and morale. This was central to the thinking of Taiichi Ohno when he placed standardization at the foundation of the TPS House. If everybody follows the same process in the same sequence, discrepancies (when they arise) are much easier to identify and correct.

I believe that reinforcing this idea was Takahashi-san’s mission as our trainer. He was very determined to see us grow in that area. Takahashi-san and another very experienced trainer, Mr. Honda, were very present in those early days, observing and enforcing the principles of TPS to each of us as the plant’s production ramped up. They were always there for us, ready to answer our questions. I enjoyed spending time with them (I even taught Takahashi-san some English slang, and he taught us several Japanese words) and felt extremely lucky to get to know these incredibly wise people.

This is not to say that my relationship with my trainers was all nods and smiles. We were expected to work very hard, and they could be very stern. And I, at 19, could be a bit headstrong and competitive.

I remember the process we had in place for installing bolts in the backside of the instrument panel to hold the wiring harness in place. This was done with a nutrunner gun: we had to apply about 10 pounds of pressure to install each bolt. Because the panel was fairly wide, the standard called for the operator to install half the bolts using the right hand, and the other half using the left hand. I was really good at this, blazing through the process in 60 seconds – faster than the average. But I had learned to do it all with my right hand. I thought there was no need for my teachers to instruct me further, because I was doing the job well and didn't need to use my left hand. Besides, I didn’t feel I could control that nutrunner gun with my left hand like I can with my right.

One day, to my surprise, my trainer took me offline and asked me to leave my right hand down.

“Practice this with your left hand only,” he said. “And, please, no talking.” (This was a subtle invitation to listen more and talk less.) Then he walked away without any explanation. At that moment, I was a little perplexed because I really felt I was doing better than expectations, just by using my right hand. What was the problem? Being young with an occasional sarcastic flare, I did what I was told but remained somehow resistant the whole time. Why was the trainer making me do this? “I was meeting all the standardized work requirements,” I thought, “Why pick on me like this?”

The standard was clear, however: I had to use both hands to complete the process. Eventually, my trainer came back and asked me to explain why I had to use both hands. He waited to see how I would respond. “Do you understand why?” he asked.

“Because you said so,” I retorted.

“No,” he said, “The standard’s there for a reason.”

Then he asked me to demonstrate the process with my right hand. At one point at the end of the process, as I was straining over to my left, he said: “Stop right there, and stand for 30 seconds with that pressure down.” My body was in a bent position with a push force (ergonomically unsafe based on ratings), shoulder fully extended, but I hung on.

“Right now, you can do this same process 10 times a day,” he said. “You are a master. But 10 times a day is practice only.” He was being a little stern. “But can you do this process 100 times a day? Can you do this at full production at 540 times a day?” He was patiently trying to explain in a way I could understand and said: “I am saving your shoulder,” he continued. “Safety is why I am asking you to work with both hands. If I don’t intervene, you will end up hurting your shoulder after a while. You are at risk of cumulative trauma. So, I am really saving your shoulder. You should thank me!”

“Okay, I get it – you’re right,” I said weakly.

“That’s the first lesson,” he said. “But there is another one: one day you will be a leader, and you will have to deal with somebody who is resistant to change just like you.”

I never forgot that. As the Kentucky site progressed and became more self-sufficient using Toyota’s methods, we saw less and less influence from our trainers. Today, trainers like Takahashi-san and Honda-san are few and far between. I have grown to miss those early days with our Japanese sensei.

I was very young and naive at the time, and I hadn’t matured to the point where I could fully appreciate the perspectives our trainers were offering. Takahashi-san had very high expectations for us all, which was sometimes intimidating for a 19-year-old, but had I known then what I know now about the priceless knowledge he and our other trainers had, I would have invested much more time asking deeper questions. Even today, I wish I could spend more time with some of my past Japanese trainers. I would have so much to ask and go see!

Don’t miss The Toyota Engagement Equation, which contains this and many more stories and lessons Tracey and her husband Ernie learned while at Toyota.

THE AUTHOR

Tracey Richardson has 30 years of experience working for Toyota in different roles. She learned about lean thinking and practice at the gemba with her Japanese sensei. She is the President of Teaching Lean Inc. Her and her husband Ernie's book The Toyota Engagement Equation has recently been published.

Read more

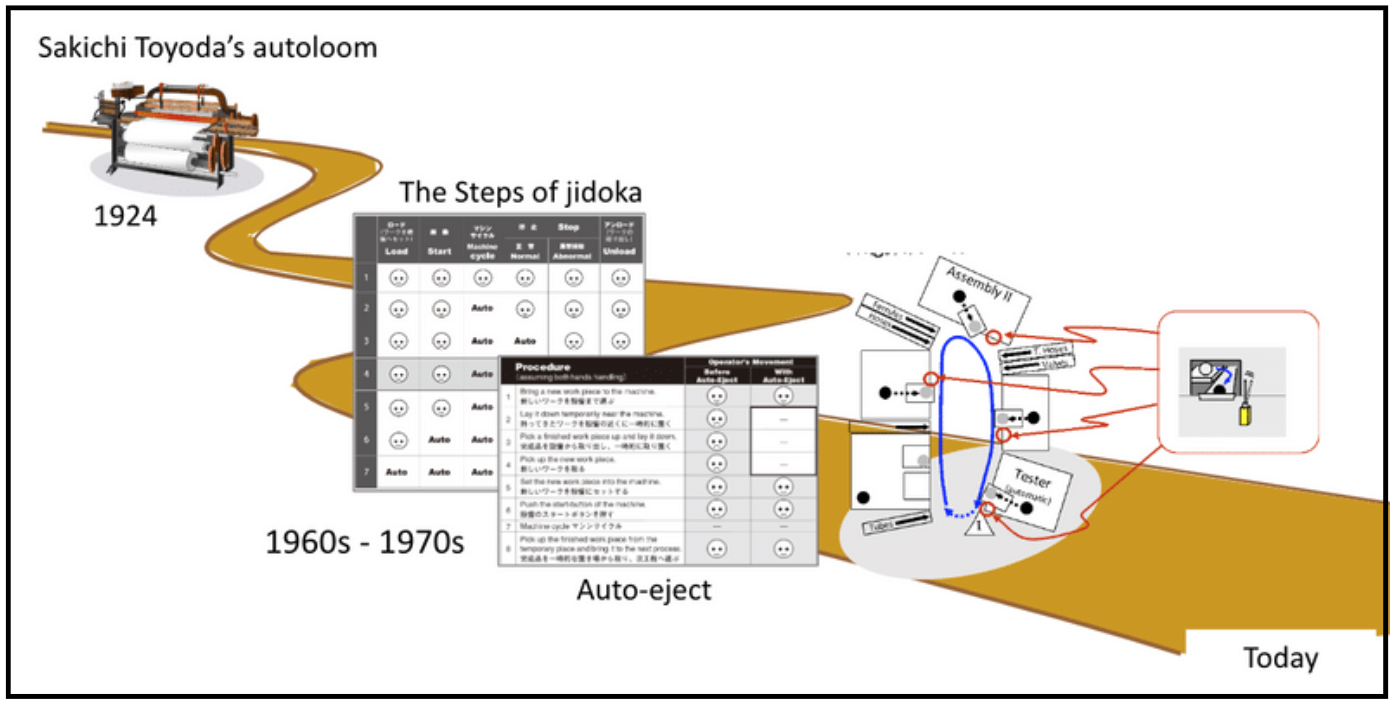

FEATURE – In the first piece of a series on Takehiko Harada’s contribution to TPS, the authors discuss the Nagara Switch and how it helps to achieve better Jidoka.

ONE QUESTION, FIVE ANSWERS – Inspiration can help us solve a problem, get our colleagues interested in lean, or even pick ourselves up after a failure. But where do we get it from? We asked five practitioners.

FEATURE - Develop your people if you want to develop a better (lean management) system in your business. This is the key message of this article, which looks at the role of management in an organization and in society.

FEATURE – This year, PL will try to understand what the future of work looks like in a world with AI. To kick us off and make us think, we publish an article that is the result of a one-hour conversation between a human and a machine.